Obstetric fistulas are aberrant connections between the genital tract, urinary tract, or gastrointestinal tract.1 The causes and prevalence of obstetric fistula differ between high and low-resource settings. Obstetric fistulas most commonly affect women in resource-limited settings where fertility is high, obstetric healthcare is limited, and the socioeconomic status of women is poor. Therefore, obstetric fistulas in resource-limited settings often correlate with high maternal mortality.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates 130,000 new cases of obstetric fistula per year in developing countries.3 Additional estimates detail 1 million women in Nigeria and 110,000 women in Ethiopia who currently have obstetric fistula.4,5

The etiology of obstetric fistulas in resource-limited settings is most commonly pressure necrosis secondary to prolonged obstructed labor related to reduced access to health services, home delivery, and lack of infrastructure.1,6,7 In contrast, obstetric fistulas in high-resource settings are much less common and are most often due to surgical complications.8–11

Social Implications of living with obstetric fistula have been well documented in the literature.12–15 A poignant description in a semi-structured interview of 17 Ugandan women with obstetric fistula detailed that women suffered anywhere from several months to 21 years from isolation, divorce, abandonment, ostracism, and malodor before receiving treatment.6 Therefore, a cure through surgery may be vital for social integration, holistic well-being, and the resumption of daily activities.

Treatment of obstetric fistula, regardless of size, location, and complexity, follows three basic principles. Sufficient fistula mobilization is required for a water-tight repair without tension at the suture site.16,17 Additionally, post-operative care must include routine bladder emptying to ensure minimal pressure at the closure site.16,17 In some cases, with complex or significant defects, vascular flaps such as the bulbocavernosus fat pad, Singapore, and gracilis muscle may provide additional tissue for repair.18–20 The success of surgery has typically been defined as retained closure, continence, reproductive capacity, and societal acceptance.1 Little is known about the long-term outcomes of surgical repair. Current evidence suggests that obstetric fistula survivors have reduced fertility and increased complications.21,22 Nevertheless, surgical outcomes are often associated with size, scarring, and degree of damage to the urethra and bladder.23–26 Currently, it is unknown which types of fistulas are more likely to result in adverse outcomes or further complications.

There is currently no unified classification scheme for accurately describing obstetric fistulas, thereby limiting communication between surgeons and the ability to compare research. Frajzyngier et al. examined prognostic values of classification systems and found them to be “poor to fair”.27 Goh’s classification is based on the location of the fistula in relation to the external urethral orifice, the size of the fistula, and the extent of scarring or other subjective factors that might predict success.28 Waaldijk’s classification is also based on the urethral closing mechanism and size with increasing complexity from type I to III. However, the preoperative classification does not significantly predict the outcome of surgery.29 Many other factors related to surgical failure/success have not been explored, and surgeons currently do not universally use the same classifications. The development of a new, universally accepted, and utilized classification scheme for obstetric fistula may provide the tools to compare surgical techniques, outcomes, and complications to improve patient care. This study, therefore, aims to assess which factors are the most important to include in a future classification scheme.

METHODS

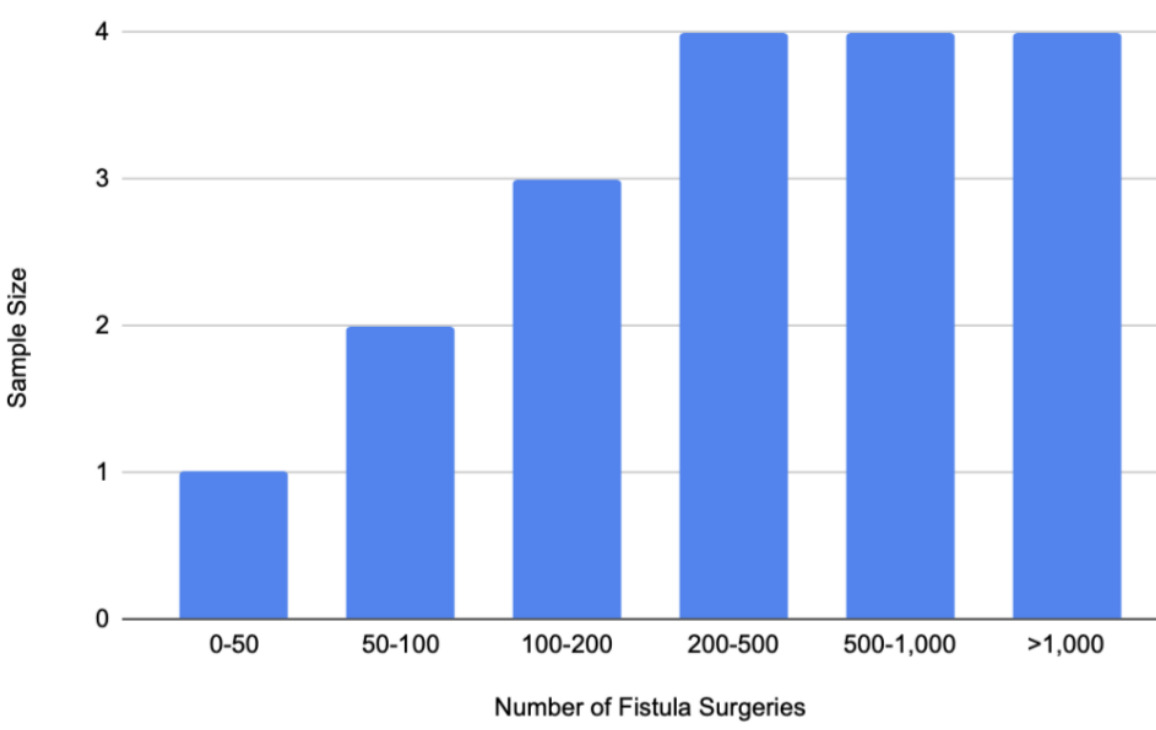

Members of the International Society of Obstetric Fistula Surgeons (ISOFS) were contacted via email and solicited to participate in a non-validated questionnaire designed by the authors (Appendix A, Online Supplementary Document). The questionnaire included demographic information such as age, country of residence, and countries where the surgeon performed obstetric fistula repair. Surgeons were asked to report the number of obstetric fistula surgeries they have performed stratified by 0-50, 50-100, 100-200, 200-500, 500-1,000, or over 1,000. The questionnaire next asked surgeons to determine whether the following factors were important determinants to include in an obstetric classification system and to rank the following factors on a scale of 0- not at all important to 10- of vital importance: location of the fistula, how long the patient has had a fistula, whether the fistula is circumferential or not, degree of fibrosis, fibrosis of the vagina, degree of damage to the vagina, vaginal scarring, history of previous fistula repair, bladder size, degree of urethral damage, whether the urethra is blocked or not, urethra length, intraoperative complications, and skill of the operating surgeon. Surgeons were asked to list any other factors they thought were important to include in a comprehensive obstetric fistula classification system. Finally, surgeons were asked to determine what their definition of a cure, or healing, following an obstetric fistula repair surgery, is from the following factors: retained closure of the fistula, a lack of ongoing incontinence, the patient’s perspective of the result of the operation, or any other factors. Surgeons were then asked to explain why or why not they found the previous factors essential or not important. Based on the surgeons’ response, an average ranking of each determinant of obstetric fistula classification system was computed.

RESULTS

Eighteen surgeons completed the questionnaire. 12 “expert” fistula surgeons completed the surveys. Experts were defined as surgeons who have completed over 200 fistula surgeries. The cutoff point of 200 surgeries is based upon current obstetric fistula training programs. 200 surgeries is the minimum number at which a surgeon might have achieved advanced training per these programs.30,31 The remaining six surgeons completed less than 200 procedures, with n=3 reporting performing 100-200 procedures. Figure 1 displays the expertise levels of the surgeons stratified by the number of obstetric fistula surgeries performed.

Surgeons were asked which factors they felt were essential to include in a comprehensive obstetric fistula classification system. Additionally, the surgeons ranked these factors on a Likert scale of zero to ten, with zero of minor importance and 10 of utmost importance. The results are displayed in Table 1. The most critical factors that surgeons found necessary to include in an updated fistula classification system are the bladder size (88.9%, n=16, 8.53), degree of fibrosis of the vagina (83.3%, n=15, 8.12), degree of urethral damage (88.9%, n=16, 9.34), location of the fistula (100%, n=18, 9.22), urethral length (94.4%, n=17, 9.06), and whether the fistula is circumferential or not (94.4%, n=17, 9.18). The least important factors were how long the patient had had a fistula (11.1%, n=2, 2.28) and intraoperative complications (22.2%, n=4, 4.59). Factors of intermediate importance included the degree of damage to the vagina (55.5%, n=10, 7.11), fistula size (7.33), history of previous fistula repair (77.7%, n=14, 8), the skill of the operating surgeon (55.5%, n=10, 6.29), vaginal scarring (61.1%, n=11, 7.71), whether the urethra was blocked or not (44.4%, n=8, 6.34).

It was of interest whether surgeons of different experience levels rated the importance of these factors differently. Appendix B in the Online Supplementary Document includes figures that stratify importance ratings per category by surgeon experience level. For most factors important in repair, there was a non-significant correlation between experience level and ratings from 0-10. Scores for urethral length showed a significant correlation between increased surgical experience and higher ratings of importance.

Surgeons were asked what they felt were significant determinants of a cure for obstetric fistula - the results are listed in Table 2. Surgeons reported that consistent urinary continence was the most important factor determining a cure (94.4%, n=17). Expert surgeons reported that this was an important factor because “this is the primary aim of fistula repair - to relieve the symptoms for which she sought care. You need to close the fistula and also take measures to prevent ongoing urethral incontinence.” and “Lack of incontinence will be the best guarantee for social reintegration.” The single expert surgeon rated this unimportant because “It does not determine a patient’s satisfaction with their condition. I am only interested in what the patient perceives as a successful outcome. This is about patient satisfaction and its impact on quality of life.”

Factors that were deemed less important determinants of a cure of obstetric fistula were the retained closure of the fistula (27.7%, n=5), resumption of sexual activity (27.7%, n=5), and the patient’s perspective of a cure (33.3%, n=6). Expert surgeons reported that retained closure of the fistula was not a critical definition of a cure because incontinence may persist despite a closed fistula due to several factors, including but not limited to stress incontinence, short urethra, and a small bladder. The expert surgeons who reported that retained closure of the fistula was important reported that fistula closure is a prerequisite for continence and that continence is the primary goal of obstetric fistula repair. Expert surgeons reported that the resumption of sexual activity was not an essential definition of a cure did so because “restored continence is more important for social reintegration than being able to have vaginal intercourse. Sexuality is not limited to intercourse.” and “[sexual activity] does not determine [a] patient’s satisfaction with their condition. I am only interested in what the patient perceives as a successful outcome. This is about patient satisfaction and its impact on her quality of life.” Sexual activity was deemed an important definition of a cure by n=5 surgeons as the resumption of sexual activity allows for a higher likelihood of marriage and vaginal delivery and that it allows for the resumption of typical daily activities. The patient’s perspective of a cure was not crucial to some expert physicians as the general definition for successful obstetric fistula surgery is the full resolution of incontinence.

DISCUSSION

Obstetric fistulas are most commonly a disease of poverty resulting from inadequate obstetric healthcare leading to urinary incontinence, isolation, divorce, abandonment, and ostracism.1 Currently, there is no universally accepted classification scheme with a reliable characterization of fistula location or sufficient prognostic value.

Upon survey of experienced and expert fistula surgeons, the following factors were deemed as most important for a classification scheme: bladder size, degree of fibrosis of the vagina, degree of urethral damage, location of the fistula, urethral length, and whether the fistula is circumferential or not. Three of the most commonly used classification schemes by Goh, Waaldjik, and WHO only capture some important factors determined by the surgeons.27–29 The Goh classification includes essential factors such as bladder capacity seemingly as a function of bladder size, fibrosis of the vagina, and the circumferential defect. It does not include the degree of urethral damage and urethral length. The Goh classification notably allows for a more precise characterization of the location of the fistula than does Waaldjik and WHO; however, its characterization of location is a function of the distance from the external urinary meatus and does not account for whether the fistula is lateral to the sagittal plane of the urethra.27–29 While both the Waaldjik and WHO classification systems include the presence of a circumferential defect, they do not characterize bladder size, the fistula’s location, and the urethral length.27,29 The WHO system utilizes “degree of tissue loss” and “involvement of the urethra/continence mechanism” as proxies to determine the damage to the urethra. Still, it does not provide enough specific information.27 Similarly, Waaldjik allows classification based on subtotal or total urethra involvement.29

Surgeons determined that the following factors were of lesser importance: how long the patient had had a fistula, intraoperative complications, degree of damage to the vagina, fistula size, history of previous fistula repair, the skill of the operating surgeon, vaginal scarring, and whether the urethra was blocked or not. All three classification schemes include fistula size.27–29 The Goh Classification scheme includes prior fistula repair.28 Any of the three classifications did not include the remaining factors.27–29 Fistula size was deemed of intermediate importance by the surgeons receiving a mean score of 7.33. While surgeons found other factors important to include, this data may indicate that a smaller proportion of the classification scheme should focus on characterizing the size, and more emphasis should be placed on surgeon-reported critical factors such as bladder size, vaginal fibrosis, urethral damage, location, urethral length, and circumferential defect.

Given the inconsistency between what experienced and expert surgeons deem important determinants for the classification of obstetric fistula, these authors call for constructing a new, validated classification system. This system should expand upon Goh’s classification of the location of the fistula to include characterization of the laterality of the fistula and include factors such as degree of urethral damage, urethra length, and bladder size. Additionally, this classification scheme should be tested for homology amongst surgeons to ensure that surgeons consistently categorize fistulas correctly according to the newly constructed system. A universally accepted and utilized classification system with greater applicability to the variability of obstetric fistula presentations would allow for comparative research in terms of the complexity of repair, the required skill of the operating surgeon, the best surgical approach, and expected outcomes. This classification system would provide surgeons with the tools to better treat obstetric fistula, thus yielding improved patient outcomes.

This study has several limitations, primarily due to the small sample size and the lack of a validated questionnaire. Recruiting a small sample size may hamper the generalizability of our findings to fistula surgeons at large. A small sample increases the risk of biased results and reduces statistical power. Additionally, expanding the sample size would enhance the study’s credibility and strengthen the external validity of the findings, allowing for more accurate generalizations to the broader population. Furthermore, the absence of a validation process for the questionnaire raises concerns about its reliability and accuracy in measuring the intended constructs.

CONCLUSIONS

Three of the most commonly used classification schemes by Goh, Waaldjik, and WHO only capture some important factors determined by the surveyed surgeons. Given the inconsistency between what experienced and expert surgeons deem to be important determinants for the classification of obstetric fistula and what is currently included in classification systems, these authors call for constructing a new, validated classification system. This system should expand upon Goh’s classification of the location of the fistula to include characterization of the laterality of the fistula and include factors such as degree of urethral damage, urethra length, and bladder size.

Ethics statement

An. IRB exemption protocol under STUDY20220532 was accepted. Consent was assumed by participants who completed our questionnaire.

Funding

The APC was funded by the Roe Green Global Health Scholarship at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.

Authorship contributions

Elad Fraiman: Survey Construction, literature review, data analysis, manuscript writing

Rachel Pope: survey construction, survey distribution, manuscript editing

Disclosure of interest

The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form and disclose no relevant interests.

Correspondence to:

Elad Fraiman

Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine; University Hospitals Cleveland Urology Institute

9501 Euclid Ave, Cleveland, OH 44106

USA

[email protected]