Global health issues, such as COVID-19, are quickly disintegrating the boundary between global and national health. Such issues have increased the need for national health experts to obtain knowledge and skills in global health. One approach toward strengthening the global and national capacity for health is for health experts to be engaged in work at health-related UN/international organizations and nongovernmental organizations and return their newly acquired knowledge and skills to their original workplaces or societies upon their return. The reciprocal value of health experts’ participation in overseas work is emphasized in several international reports and studies.1–4

The placement of health experts to international organizations is also associated with the issue of underrepresentation of UN member states. This issue poses a challenge to “recruiting staff on as wide a geographical basis as possible” prescribed in Article 101 of the United Nations Charter.5 The Geographical Diversity Strategy of the United Nations’ Office of Human Resources sets the following goal: “every unrepresented member state be represented in the organization and to bring as many underrepresented member states to be within range in the system of desirable ranges”.6

Since the mid-2010s, the Japanese government has been promoting human resource development and dispatch of global health personnel (herein broadly indicating medical and non-medical experts interested in global health) to health-related international organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), and Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM) (hereafter referred to as health-related international organizations). In 2016, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare released a policy proposal “Report by the Working Group on Human Resources Development for Global Health Policy”7 to develop and increase leaders in global health.

Nevertheless, there is still shortage of Japanese global health personnel working at health-related international organizations. The number of health-related professional staff working at the six major international organizations (WHO, Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS, United Nations Children’s Fund, UNFPA, GFATM, and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance) has gradually increased from 77 (1.8%) in 2017 to 79 (1.7%) in 2018, 84 (1.8%) in 2019, 96 (1.9%) in 2020, and 97 (1.8%) in 2021.8 However, several UN organizations employ fewer Japanese professional staff than the official desirable range calculated based on elements, such as financial contribution and population. For instance, the desirable range for the WHO Western Pacific Region is 94 to 128; however, only 40 staff are employed.9

To date, research on global health collaboration and partnerships have mainly focused on the documentation of reciprocal values of international partnerships.1–4 There is a little research on the placement of global health personnel in health-related international organizations focusing on the required competencies and skills or gap between actual qualifications possessed by global health personnel and international standards or proposals for their development.10–12

The present study aimed to determine the job preferences of Japanese global health personnel when making job choices for health-related international organizations using discrete choice experiment (DCE). DCE is based on the Lancastrian theory, which suggests that the use of a good or service is defined by its characteristics (attributes).13 Hence, by presenting the hypothetical job scenarios described by combinations of different attributes and levels, and statistically modeling the choices of study participants, it estimates the impact of each characteristic on the applicants’ utility or probability of accepting the job. Based on the assumption that understanding the applicants’ insights on job preferences is the key to elucidating the reason for nonapplication and underrepresentation, DCE was chosen to complement the market-oriented approach adopted by previous studies10–12 and ongoing career development seminars focusing on the required competencies. Based on the job preferences, the current study aimed to inform researchers and policymakers of the priority areas that need improvement. Given that the employment conditions of international organizations are internally decided, such as through the United Nations Common System, we intended to establish policy proposals on areas practical and amenable to change, namely, on national stakeholders’ approaches.

METHODS

The conduct of this study involved two phases: (i) development of job attributes and levels mainly through qualitative interviews and (ii) implementation of the DCE questionnaire survey (Online Supplementary Document).

Developing attributes and levels

Prior to the qualitative interviews, potential attributes were broadly predefined through literature review14–17 and discussions among co-authors. Based on these predefined sets of attributes, in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted from May 2019 to January 2020 on 20 Japanese global health personnel, of whom 13 wished to work at health-related international organizations (Seekers), 4 were currently working at these organizations (Workers), and 3 resigned from these organizations (Resignees). Three groups across the career stage were included to determine whether any characteristics or tendencies were unique to each group. The participants were initially chosen from those working at the National Center for Global Health and Medicine and international organizations in Tokyo/abroad and gradually increased through snowball sampling. During the interviews, 11 predefined attributes (contents of the job, opportunity for self-realization, opportunity for capacity development, salary, welfare, job location, work–life balance (WLB), job security/length of contract, opportunity for children’s education, opportunity for spouse’s job, and guaranteed job upon return to Japan) were presented. The participants were then asked to select all attributes they thought were important when they consider/considered working at international organizations and arrange them in the order of importance. These were later graded to obtain an overall ranking. Then, they were asked to speak freely regarding each selected attribute and add others, if any. For the final DCE questionnaire, eight attributes and levels were defined through content analysis and further discussions with the co-authors (Tables 1 and 2). Details of the qualitative study are described in a separate report.16

Defining choice sets

The eight attributes and corresponding levels (2^1*3^7) from the qualitative interviews were organized to form a main effect orthogonal array of 18 choice sets with a 100% D-efficiency. These 18 hypothetical job profiles were presented in a questionnaire as the description of potential posts at health-related international organization with different conditions.

The present study aimed to examine not only the relative importance of the attributes but also the impact of each attribute on the expected post uptake. Therefore, the DCE was structured as an acceptance of each presented post rather than a comparison among options. To obtain detailed information on the relative importance from each respondent, they were asked to choose one answer for each choice: (1) I strongly want to take the post, (2) I weakly want to take the post, (3) I weakly do not want to take the post, and (4) I strongly do not want to take the post. Figure 1 presents an example of a choice set.

DCE data collection

Using Google Forms, three separate online questionnaires for Seekers, Workers, and Resignees were created. The first half of the questionnaire was designed to obtain information on the respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics and reasons for application and resignation from the international organization if applicable. The latter half contained the DCE questions, which were identical for all three groups. The questionnaires were pilot-tested by nine volunteers belonging to one of the three groups, after which certain formatting and wordings were amended for easier understanding and response.

Given the lack of exact sample-size calculations for choice experiments and practical limitations during the recruitment, we asked each respondent the full set of 18 questions while also aiming to obtain a minimum sample size of 30 respondents per subgroup, which is recommended based on econometric criteria.17

Questionnaires were sent out to more than 12,669 members of the following mailing lists from May to June 2021. The numbers in the brackets are the membership numbers of these mailing lists as of May 2021: Human Resource Registration and Search System managed by the Human Resource Strategy Center for Global Health (HRCGH)22 (621), HRCGH (637), UN Forum (8,630), Japanese Alumni of London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (181), School of Public Health Japanese Community (950), Japan Association for International Health Student Subcommittee (1,650), and Japanese Staff Association of International Organizations in Geneva (number of members unknown). These media were selected considering that they included Japanese members interested in global health and belonged to one of the three target groups.

We received 154, 33, and 32 responses from Seekers, Workers, and Resignees respectively. After carefully scrutinizing the data, we retained responses that suited one of the three categories and had no inconsistencies in personal information. We excluded duplicate data, those with incorrect categorical input, and those with inconsistencies in personal information. The final sample sizes were 150, 31, and 31, respectively.

DCE data analysis

The model presented here is a binary logit main effects model with the accept/not accept threshold. (The four response options were classified as “accept” or “not accept”. While an ordered logit model was run on the full strength of preference responses, these were consistent with the binary results presented here. The binary logit model also allows for predicted uptake rates to be presented with these same estimations).

Changes in salary were included as a continuous variable whereas others as dummy coded variables, with the most typical value as the reference level for ease of interpretation.

The underlying utility function for respondent choosing alternative is as follows:

\[u_{ij} = \beta_i x_{ij} + \varepsilon_{ij}\tag{1}\]

such that the presented role is “accepted” if the respondent had a positive expected utility from accepting this. The term is the observable vector of attribute levels in the DCE forming the deterministic portion of the utility, whereas is an unobservable error independently and identically distributed over alternatives.

The three sample categories were separately analyzed, with the results being presented sequentially. All statistical analyses were conducted in Stata 16.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Tokyo Women’s Medical University (Reference no. 5185). The participants of the qualitative interviews were informed of the research and provided written informed consent. Participants of the DCE survey were informed, in writing, about the research and that replying to the questionnaire indicated their consent to participate.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics (age, social status, possession of medical qualifications, etc.) widely varied within and between subgroups (Table 3). Of the Seekers, 92 (61.3%) respondents held medical qualifications, out of which 38 (41.3%) were nurses, 26 (28.3%) were doctors, and 12 (13.0%) were pharmacists. Of the Workers, 14 (45.2%) respondents held medical qualifications with majority being doctors (10, 71.4%). Of the Resignees, 19 (61.3%) respondents held medical qualifications, out of which 9 (47.4%) were doctors and 6 (31.6%) were nurses.

Motivation for employment and reason for resignation

In the questionnaire, we requested the respondents to write freely about their motivation for working at international organizations (Table 4) and their reasons for resignation (Table 5) for the Resignees. The responses from the Seekers, Workers, and Resignees were classified into categories and presented in order from most to least frequent through content analysis.

For Seekers, “to solve problems in larger/international/multilateral environment” was the most cited motivation, followed by “to solve global health issues” and “to utilize one’s experience and expertise.” For Workers, “better labor condition” and “high evaluation of international organization/staff” were the most cited motivations, followed by “to solve global health issues.” For Resignees, “to solve global health issues,” “to solve problems in larger/international/multilateral environment,” and “aspiration from young age” were the top three most cited motivations.

Regarding reasons for resignation, “termination of contract” was most cited, followed by “family matter,” including elderly care, child education, and non-accompaniment of family members due to COVID-19, followed by “disillusionment with the organization.”

Relative importance of job attributes

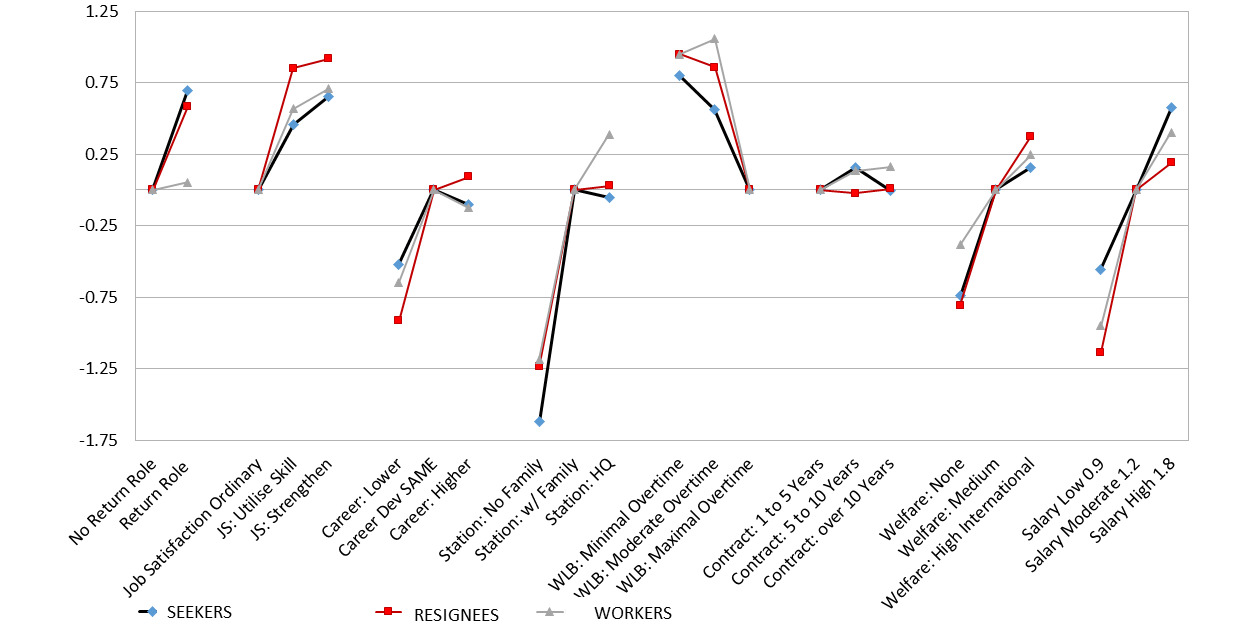

The results of the binary logit main effects model are presented in Table 6 and Figure 2.

For Seekers, aversion to the possibility of a non-family duty station had the biggest negative impact on job preference (β = −1.634, P < 0.001). The next biggest factor was the impact of salary (β = 1.268, P < 0.001). WLB was considered important, with participants preferring WLB with minimum overtime (β = 0.8128, P < 0.001) more than WLB with moderate overtime (β = 0.5624, P < 0.001). Aversion to a post where employers did not contribute to welfare benefits also had a significantly negative impact (β = −0.7732, P < 0.001); however, the participants did not significantly prefer the generous welfare schemes of international organizations over the baseline welfare benefits typically provided in Japan (β = 0.1456, P < 0.252). Having a guaranteed return post in Japan was also highly preferred (β = 0.7389, P < 0.001). The specific job satisfaction levels were also valued, with “strengthening capacity and skills” (β = 0.6281, P < 0.001) being more preferred than “utilizing one’s expertise, capacity and experiences” (β = 0.4626, P < 0.001).

For Workers, salary had the biggest impact on job preference (β = 1.435, P < 0.001), followed by aversion to non-family duty stations (β = −1.183, P < 0.001). WLB with moderate overtime (β = 1.071, P < 0.001) and minimum overtime (β = 0.916, P < 0.001) were also both statistically significant factors in decision-making. The options for job satisfaction were valued, with “strengthening capacity and skills” (β = 0.6308, P < 0.011) and “utilizing one’s expertise, capacity and experiences” (β = 0.5951, P < 0.019) showing similar preference patterns. Unlike for Seekers and Resignees, guaranteed return post in Japan had the least impact among all attribute levels for Workers.

For Resignees, salary had the biggest impact (β = 1.274, P < 0.001), followed by aversion to non-family duty stations (β = −1.265, P < 0.001). WLB also had a significant impact, with minimum overtime (β = 0.8392, P < 0.001) being slightly more preferred over moderate overtime (β = 0.7851, P < 0.001). Job satisfaction was also important, with the specific option for “strengthening capacity and skills” (β = 0.7891, P < 0.001) and “utilizing one’s expertise, capacity and experiences” (β = 0.7624, P < 0.001) having similar positive impact. Aversion to a post where employers did not contribute to welfare benefits also had a negative impact (β = −0.7642, P < 0.002); however, the generous welfare schemes of international organizations had no significant impact (β = 0.3505, P < 0.145). For this group, a guaranteed return post in Japan also had a significant impact (β = 0.6467, P < 0.001).

Given that the DCE estimated coefficients are not directly interpretable, the results for each sample are also presented as Willingness to Pay (WtP) in Table 6. Apart from having more inherent meaning, the WtP can also be compared more meaningfully across the sample groups.

Predicted uptake of different job profiles

Estimates for the expected uptake of various posts can be calculated using the part-worth coefficients from the binary logit model for each group. Hence, several important or interesting post profiles were chosen to estimate the expected uptake, with significant differences across the posts.

With all job attribute levels set to the baseline of what is considered typical for international organizations, 86%, 85%, and 76% of Seekers, Workers, and Resignees would accept the offered post. These uptake rates increased to 98%, 97%, and 94% when all the attribute levels were set to what are considered the most preferred jobs for these groups and decreased to 5%, 5%, and 2% for the worst possible post descriptions for each group, respectively. Other selected posts of comparative interest along with post attribute descriptions are presented in Table 7.

Included in this are the attribute values from typical Japanese posts, enabling us to estimate the uptake of such a post if it were at a health-related international organization. For the closest match to a typical Japanese post description, the uptake would need to be 55%, 38%, and 26% across the three groups, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The DCE has been used in various studies to examine the job preferences of health professionals, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where human resource shortages are imminent, especially in rural, underserved areas.23–26 However, this has been the first study to address the issue of health-related staff shortage at the international organizations by examining the job preferences of global health personnel using a DCE. By adopting the DCE method, we hoped to focus on the in-depth preferences and needs of the respondents to complement the previous research mainly focusing on the analysis of the required skills and competencies.

One general trend across all three groups, which supports the psychology and behavioral economics literature, is the generally stronger impact of a loss compared with a gain across the levels within any attribute. Respondent choices support the loss aversion literature.27 They also suggest that the positive impacts of other attributes can compensate for the negative impacts, although negative impacts were more significant and more consistent among the respondents, as indicated by the statistical significance of the results.

In relation to this, another trend was the appearance of strong “uncertainty-avoidance” characteristics in certain groups. The characteristics of “uncertainty avoidance” is defined by Hofstede as “the extent to which a society feels threatened by uncertain and ambiguous situations and tries to avoid these situations by providing greater career stability, establishing more formal rules, not tolerating deviant ideas and behaviors, and believing in absolute truths and the attainment of expertise”.28 Hofstede and other literature on organizational behavior highlighted the “uncertainty-avoidance” characteristics of Japanese employees where security needs excel over other needs, such as self-actualization, esteem, and social needs.28,29 The fact that attribute levels such as aversion to non-family duty stations, aversion to a post where employers do not contribute to welfare benefits, and a guaranteed return post in Japan had high impact for the Seekers and Resignees groups supports this presumption. However, interestingly for Workers, although aversion to non-family duty stations had high impact, the other two attributes did not. In fact, the guaranteed return post had the least preference among all attribute levels for Workers, which provides interesting insights into what makes a successful candidate.

The respondents in all three groups exhibited a strong inclination to reject posts at non-family duty stations. This result closely reflects the findings of the qualitative interview, in which “duty station” was considerably important for all groups in terms of safe and secure working and living conditions.16

One approach to alleviating the uncertainty and motivating them is to provide correct information on duty stations as one element in an incentive information package and disseminate it at career development seminars. Unlike most Japanese workplaces where the assignment place is prearranged by the management, duty stations at international organizations can be selected at one’s discretion by passing the competitive examination test for the post. Thus, duty stations can be decided depending on one’s preference, objective, family, and lifestyle. At the career development seminar, the fact that there are various organizations with different missions, specialized fields, activities, etc., and that one need not be assigned to places where one feels uncomfortable can be emphasized.

The existence of a guaranteed post in Japan where one can return to after leaving the international organization was considered important by Seekers and Resignees. Surprisingly, however, it had the least impact among all attribute levels for Workers. This attribute was included in the DCE based on the hypothesis that a guaranteed post in Japan becomes a safeguard and motivates more people to apply for overseas posts and that it would be highly preferred by the Workers currently working on fixed term (therefore, precarious) contract basis. On the other hand, as the current norm is to not have a guaranteed post, Workers have still been willing to take this post without a return post, thereby possibly reflecting a self-selection and survivorship bias in the sample population of Workers. Indeed, the DCE findings indicated that those who are decisive enough to participate in global health activities without anxiety of not having return posts are currently surviving and playing active roles in international organizations. This finding is consistent with those of the qualitative interviews, from which mixed opinions were obtained; while some were anxious about the lack of Japanese hospitals and organizations that would deservedly appreciate the experiences gained overseas and accept returnees, others were quite optimistic about job hunting upon returning to Japan and assumed things will work out somehow.16

The “uncertainty-avoidance” characteristics mainly perceived in Seekers and Resignees suggest two different strategic policy approaches. One is an approach to “support a few selected ones” by focusing on supporting those who have international experiences/achievements and are firm and ready to work overseas. This approach has already been adopted by various stakeholders, such as the Junior Professional Officer System run jointly by the UN organizations and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs,30 Global Health Volunteer Initiative by the United Nations Volunteers Program,31 and the annual recruitment mission targeting Japanese nationals by the World Bank.32 The common factor among these recruitment systems is that successful candidates are selected after a highly competitive and narrow selection process. This approach has also been adopted by HRCGH by focusing on nurturing a few global health leaders. Another approach is to “enhance the overall international experience of Japanese health experts” by supporting the majority who are interested but remain uncertain and indecisive in working overseas. For this approach, the following measures are suggested: (i) creation of subsidy system for short-term studying/internship abroad for health personnel by the government and private corporations similar to “Tobitate! (Leap for Tomorrow) Study Abroad Initiative” supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports Science and Technologies and various private corporations33; (ii) creation/expansion of secondment/personnel exchange systems by the government, private corporations, universities, etc., for overseas health cooperation; and (iii) introduction of sabbatical leaves or reemployment systems of returnees by hospitals, universities, research institutions, etc. The common factor of these approaches is that they provide learning opportunities and job securities for the majority of candidates who are interested but still remain uncertain to risk their entire career by launching on a full-scale overseas dispatch. It is assumed that not all will decide to work at international organizations after these provisional overseas learning/job experiences; however, there is evidence that even short-term work abroad improves personal capacity development, particularly in cultural competence and sensitivity.4 These participants become champions of global health within their home institutions encouraging others for global health work involvement.4 This positive effect of overseas dispatch would be beneficial to Japanese health facilities where the number of foreign staff and inbound patients is increasing due to health globalization.

Another trend common for all three groups were that they preferred a combination of financial and non-financial incentives. In various other DCE studies, this tendency had also been identified, although in a different context of health workers’ job preferences in LMICs.34–39

The DCE covered the realistic salary range (i.e., from 90% to 180% of the expected salary in Japan), with higher salaries being highly preferred by all three groups while acting as a significant factor in decisions. Surprisingly, this result contradicts the findings of the qualitative interview, where the participants mainly expressed modest interest in salary that can be summarized as expectations for “minimum amount to support daily subsistence” or “amount to support family”.16 One reason for such discrepancy may be that the qualitative interview did not indicate concrete salary figures as attribute levels, and such attribute levels were left to interviewees’ preconceptions, whereas the DCE questionnaire clearly indicated the attribute levels, thereby leading to difference in interests. Another reason may be that, as mentioned in other studies,25,39 discussing openly about salary expectation may be culturally sensitive, thereby leading to the expression of modest expectation. This may be related to the significant effects of social desirability bias in face-to-face interviews, such that respondents become less willing to directly mention their prioritization of salary and material benefits of the post.40 The presentation of salary-related questions requires careful consideration in future qualitative studies.

WLB with minimum and moderate overtime were both highly valued by all three groups. This result is also consistent with the findings of qualitative interview where WLB was valued mainly due to past regrettable experiences where WLB could not be obtained due to the poor working environment.16 UN staff are entitled to various paid leaves,41 with a survey demonstrating that 80% of targeted Japanese staff working at UN organizations considered UN working hours shorter or the same compared with Japanese organizations.15

Given that the attribute levels of salary and WLB were based on actual salary levels and working conditions of UN organizations, it would be reasonable to include them in an incentive information package, together with information on duty station, to be publicized during career development seminars.

Attribute levels regarding job satisfaction (i.e., opportunity to strengthen capacity and skills and opportunity to fully utilize one’s expertise, capacity, and experiences) were moderately important for all groups, with negligible difference in preference between the two levels. As shown in Table 1, we wanted to avoid the use of generic descriptions, such as high, ordinary, and low job satisfaction, as these would have become subjective to each individual and provide only little policy relevance. Thus, we used the two identified and highly preferred descriptive levels during the qualitative interviews. The reason for the relatively moderate preference may be that people’s motivation for working at an international organization widely differs, as presented in Table 4, and that these two levels could not capture all the needs of the respondents. Another reason maybe that, as mentioned earlier, due to the “uncertainty-avoidance” characteristics of the respondents, the security needs actually exceed over other needs, such as self-actualization, esteem, and social needs, as suggested by other research.29 This remains to be investigated, but in any case, reflection is needed on how to present job satisfaction in both DCE and policy owing to its subjective and ambivalent nature.

Limitations

The DCE analysis presented in this paper was based on significant previous qualitative research for the selection of attributes and levels but remains a stated preference approach. Hence, the expressed choices regarding posts may not match the actual decisions respondents would make in an actual career choice. In such a study, the specifics of particular posts, organizations, family discussions, and alternative options within Japan cannot be included. The results are relatively consistent within subgroups and are significant, although further insights derived from more specific modeling of social demographic variables or latent class might be useful. Furthermore, owing to our small sample size, we could not conduct further subgroup analyses within each group and thus could not determine whether different sociodemographic characteristics, such as occupation, sex, and life stage, influence job preferences. It would be interesting for future studies to involve subgroup analysis for different age groups to examine how respondents’ selections change according to life stage, or for different occupational groups such as doctors, nurses, and non-medicals. The latter may be particularly important, as those who possess medical qualifications may be in a better position to find jobs upon their return and may have a different sense of job security or “uncertainty-avoidance” compared with those who do not. Lastly, this study does not cover the issue of competencies and skills required to work in international organizations, such as educational qualifications, professional/international experiences, and language skills, which are highly relevant to the issue of underrepresentation. The gap between the actual qualifications of Japanese global health personnel and international standards is discussed in a separate paper.12

CONCLUSIONS

The present study used the DCE to identify the preferences of global health personnel when applying for health-related international organizations. The binary logit main effects model emphasized the significance of duty station, salary, WLB, and job satisfaction for all groups and of a guaranteed return post and employer’s contribution to welfare benefits for Seekers and Resignees but not for Workers. The “uncertainty avoidance” characteristics mainly perceived in Seekers and Resignees proposes two separate approaches, which entails supporting (i) the few selected ones, and (ii) the majority who are interested but remain uncertain and indecisive to work overseas. The social structural challenge related to the lack of national organizations and hospitals that value experiences gained at international organizations should be addressed by introducing systems such as sabbatical leaves or reemployment systems for returnees. Furthermore, an incentive information package combining both financial and non-financial incentives focusing on favorable conditions relating to duty station, salary, WLB, and job satisfaction, which could actually be achieved at international organizations, could be actively publicized at career development seminars.

We believe that this DCE study will also provide insight for other states whose personnel are underrepresented and hence aim to increase them to reflect geographical diversity to the policies and activities of international organizations. This, in turn, will be beneficial to the international organizations themselves in realizing their individual mandates and the Sustainable Development Goals, which cannot be accomplished by leaving certain regions and countries underrepresented and, therefore, underserved. This DCE study can also be applied to a wider variety of research to understand job preferences and develop support measures of other unevenly distributed or underserved job professions in need of personnel augmentation. These professions include health professionals in remote/marginalized areas and islands within high-income countries and elderly care workers in increasingly ageing societies.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all the participants who provided valuable inputs by participating in the qualitative interview and DCE survey.

Disclaimers

The views expressed in the article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policies or positions of their institutions.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by Tokyo Women’s Medical University (Reference no. 5185).

Funding

This study did not receive external funding.

Authorship contributions

EJ, TB, and TS conceptualized this study. EJ conducted the implementation of qualitative interviews and DCE survey. EJ, and TS analyzed the qualitative interview data. TB analyzed the quantitative DCE data. EJ, TB, and TS interpreted the analysis results of the interviews and DCE data. EJ and TB prepared the first draft of the manuscript. TB and TS supervised this study and contributed to the revision of the manuscript. All authors have read the final manuscript and approved the submission of the article.

Disclosure of interest

The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and disclose no relevant interests.

Additional file

Discrete choice experiment questionnaires were added as Online Supplementary Document.

Corresponding author:

Eriko Jibiki

Section of Global Health, Division of Public Health, Department of Hygiene and Public Health, Tokyo Women’s Medical University, Tokyo, Japan

Tel: 0081-090-9248-9401

E-mail: [email protected]