The postnatal period starts immediately after childbirth and lasts for six weeks (42 days).1 It is a critical period for the mother’s health and well-being. The majority of maternal deaths occur in the postnatal period,2–7 mainly in the first 24 hours.8–10 Postpartum haemorrhage is the main cause of maternal death in this period.2,6,9,11–13 Although impressive progress has been made since 2000,14 maternal mortality in Ethiopia is still high, with 267 deaths per 100,000 live births.15 In 2019, nearly two third (65.1%) of maternal deaths in Ethiopia occurred in the postpartum period,16 and postpartum haemorrhage is the leading cause of maternal death.17,18

To ensure adequate care through the postpartum period, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends regular assessment of vaginal bleeding, fundal height, uterine tonus, temperature, blood pressure, and heart rate in the first 24 hours. In addition, screening for post-partum mental health problems, advice to do physical exercise, counselling on family planning, counselling on breastfeeding and hygiene are among the care provided during the postnatal period.19 Healthy women who give a vaginal birth at a health facility should receive postnatal care in the facility for at least 24 hours, and those who give birth at home should receive their first postnatal care as early as possible within 24 hours.19 Furthermore, three additional postnatal contacts are recommended, between 48 and 72 hours, between 7 and 14 days, and during week six after birth. The contacts are opportunities for health care professionals to detect maternal health problems and intervene accordingly (including referral for specialized care if necessary).19 The Ethiopia Ministry of Health (MOH) also recommends four postnatal visits, within 24 hours, at day 3 (48-72 hours), between days 6th and 7th, and at six weeks after delivery.20,21

The 2015 Health Sector Transformation Plan (HSTP) of Ethiopia envisioned reducing the maternal mortality ratio to 120 per 100000 live births by the year 2025.22 To achieve the goal, many activities have been executed, which include the construction of maternity waiting homes around health facilities, increasing the number of facilities providing basic and comprehensive emergency obstetrics and newborn care, and ensuring dignity and respect during maternity care.23–25 Although such interventions are expected to improve maternal health care utilisation, including immediate postnatal care, information regarding the change in immediate postnatal care utilisation over time is lacking.

This study aimed to examine the trends of immediate postnatal care utilisation from the year 2011 to 2019 and to identify factors associated with immediate postnatal care utilisation using nationwide demographic and health survey data. Information on the trends of immediate postnatal care utilisation and understanding it’s contributing factors could provide insights to policy decision-makers and program managers in planning programs, priority setting, and allocating resources.

METHODS

Data sources

This study was conducted using secondary data from three Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) data sets (EDHS 2011,2016, and 2019). The objective of the EDHS survey is to provide reliable and up-to-date information on key demographic and health indicators to support the monitoring and evaluation of health-related programmes.26–28 So far, four full-scale (2000, 2005, 2011, and 2016) and two mini (2014 and 2019) Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) have been conducted in Ethiopia.28 The 2011,2014 and 2016 surveys were led by the Central Statistics Agency (CSA) of Ethiopia, and the 2019 mini EDHS was implemented by the Ethiopian Public Health Institution (EPHI), in collaboration with other national and international stakeholders.26–28 The full and mini-scale DHS are identical in design, sample selection, and methodology to assure comparability.29 A two-stage stratified cluster sampling design was used during the surveys. Each region (nine regions and two administrative cities) was stratified into urban and rural areas. In the first stage, Enumeration Areas (EAs) were selected with probability proportional to EA size. In stage two, after a household listing was carried out in all selected EAs, a fixed number of households were selected from each EA. Different data collection tools were used to gather all relevant population health data, including a woman’s questionnaire which contains maternal and child health-related questions.26–28 In this study, we present a trend analysis using data from 2011, 2016, and 2019, however, only the latest survey (DHS2019) data were used for the analysis of factors associated with immediate postnatal care utilisation.

Population

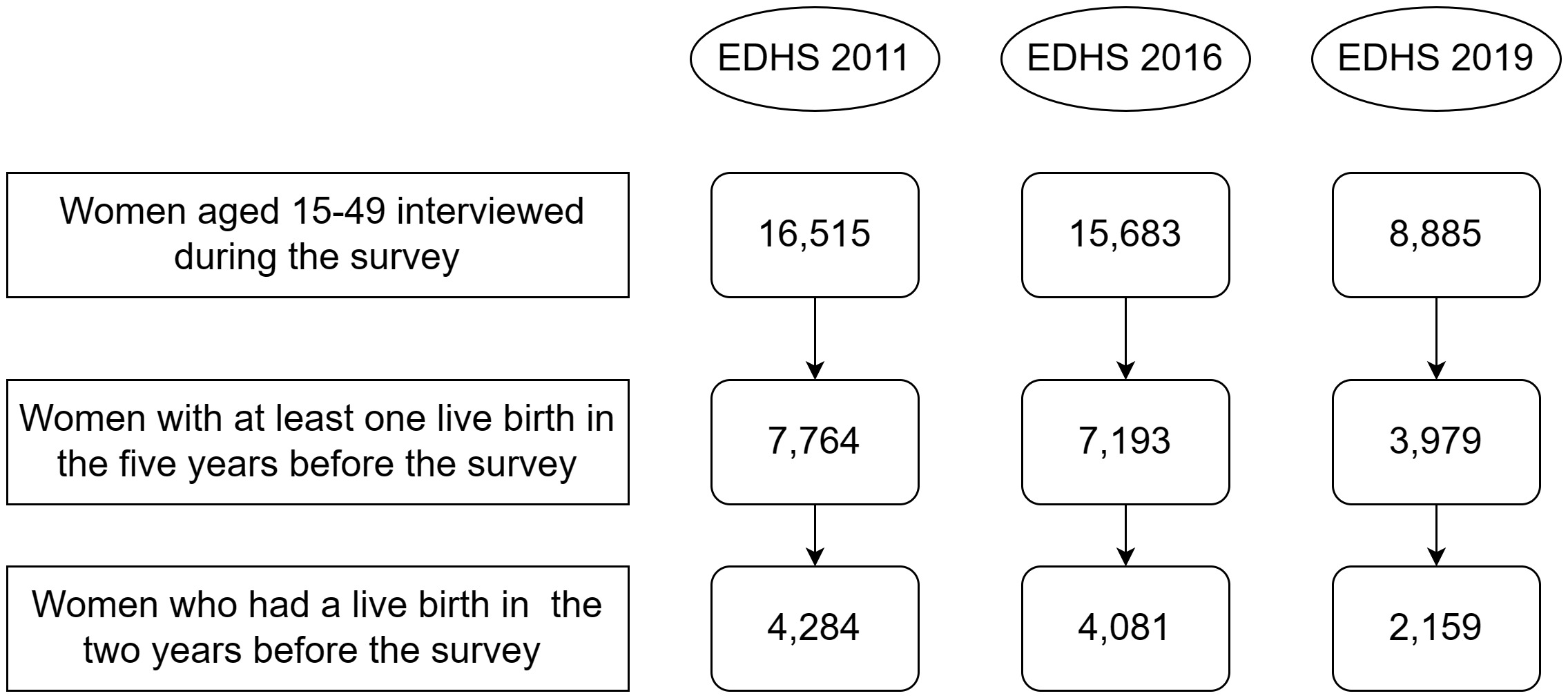

In the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), women aged 15-49 with live births in the five years before the survey were asked about their experience with postnatal care. In this study, we included only those who had a live birth in the two years before the surveys to minimize recall bias. Figure 1 shows the sample size, and the number of women included in the analysis, by survey year.

Study variables

Immediate postnatal care utilisation was the outcome variable for this study. It is a binary variable (yes/no). Two questions were asked in the DHS questionnaire to capture the utilisation of the care and the timing :(1) “Did anyone check on your health while you were still in the facility/after you gave birth to (NAME)?” and (2) “How long after delivery did the first check take place?” The answers to these two questions were merged, and the variable was coded as “1” (yes) if health was checked within 24 hours after birth, and “0” (no) if not.

Existing published literature on postnatal care utilisation from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) were reviewed.30–40 Variables that had a significant association in previous studies and are available in the 2019 EDHS data set were included as independent variables in the analysis. These variables were categorized into socio-demographic and reproductive factors. Socio-demographic factors included maternal age at the time of delivery, residence, marital status, religion, highest level of maternal education, sex of the head of the household, and household wealth index. The reproductive factors were place of delivery (grouped in two categories: in or outside a health facility), mode of delivery, sex of the child in the index birth, number of antenatal care visits, and number of children. The variables were coded based on previous studies and the distribution of responses in the data.

Data analysis

First, the data were checked for completeness, and 16 observations (women’s data) in the 2011 EDHS were removed due to missing information. The outcome variable was computed, and covariates were re-categorized and coded. To examine the trends of immediate postnatal care utilisation, the three data sets (EDHS 2011, EDHS 2016, and EDHS 2019) were appended, and a chi-square test was used to test the difference in the proportion of immediate postnatal care utilisation between the three survey years. The descriptive summary of the data was presented using tables, and a figure.

To measure the strength of the association between dependent and independent variables, crude Odds Ratio (OR) and adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR) with a 95% Confidence Interval (CI) were calculated. The association between each independent variable with the outcome variable was tested using simple logistic regression. Variables with a P-value less than 0.25 in the bivariable logistic regression were selected and fitted into a multivariable logistic regression model to identify independently associated factors through overcoming the effect of confounding variables.

Collinearity between the independent variables was tested using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). The result indicated no evidence of multi-collinearity among the independent variables kept in the final model. We considered associations to be significant with P-value < 0.05. An adjustment was made to account for the complex survey design throughout the whole analysis (adjusting for weights as a result of the sampling strategy involving stratification, and clustering). The analysis was done using R research software.

RESULTS

Socio-demographic characteristics

In the 2011 EDHS data, the information on immediate postnatal care utilisation for 16 women was missing and these observations were excluded. The data of 4268 (EDHS 2011), 4081(EDHS 2016), and 2159 (EDHS 2019) women who had a live birth in the two years before the surveys were included in the analyses. The sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1.

Reproductive health characteristics

The percentage of women who gave birth in healthcare facilities increased from 11.5% (95% confidence interval, CI=9.91-13.0) in 2011 to 36.2% (95% CI=32.2-40.0) in 2016 to 54.0 % (95% CI=47.5-60.0) in 2019. Similarly, the percentage of women who had four and more antenatal care visits increased from 17.3% (95% CI=15.2-20.0) in 2011 to 33.3% (95% CI=30.6-36.0) in 2016 to 44.0% (95% CI=39.8-48.0) in 2019. On the other hand, the percentage of women who had six or more children at the time of the survey decreased from 26.9% (95% CI=24.7-29.0) in 2011 to 20.8% (95% CI=17.5-25.0) in 2019 (Table 2).

Trends of immediate postnatal care utilisation

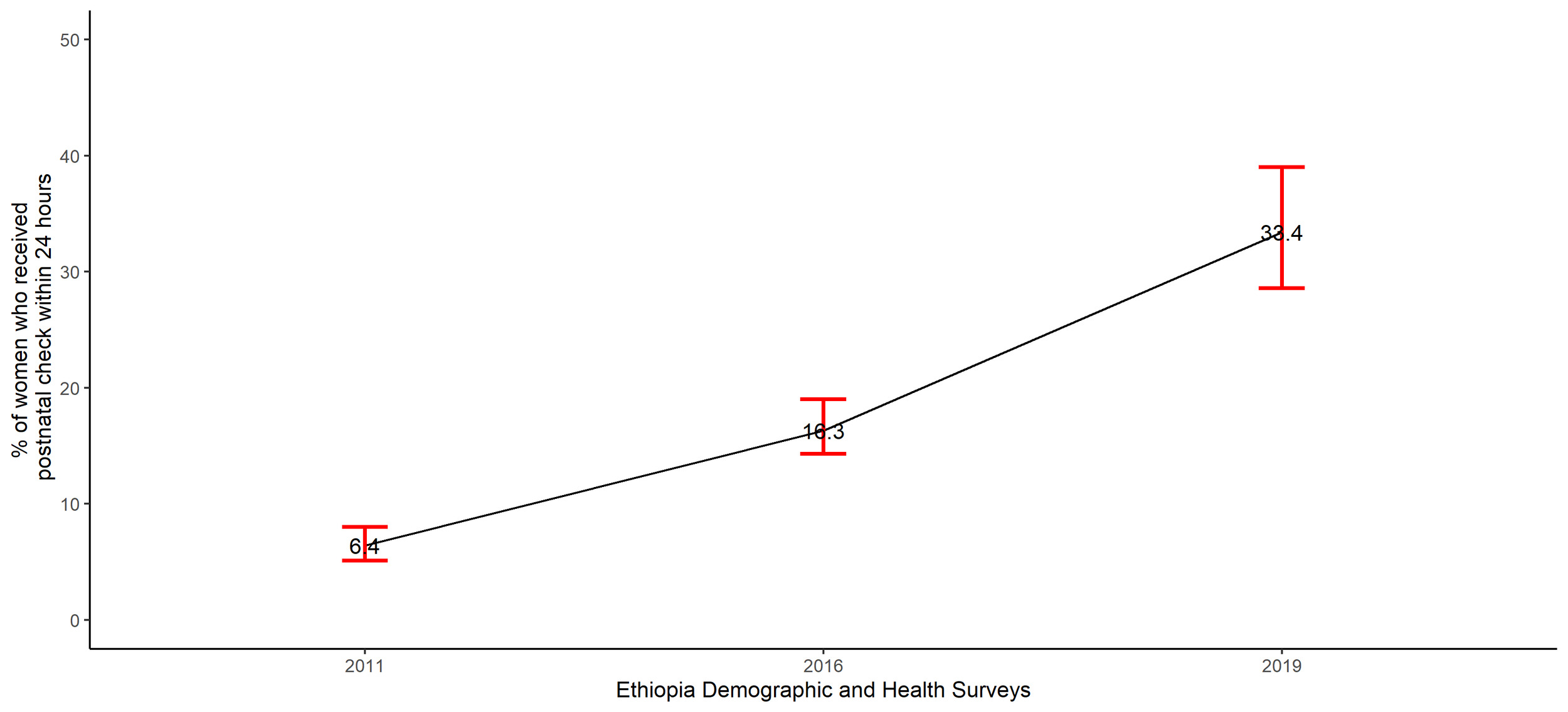

The percentage of women who received immediate postnatal check among women who had a live birth in the two years before the surveys significantly increased from 6.4% (95% CI=5.1 -8.0) in 2011 to 16.3% (95% CI=14.3- 19.0) in 2016 to 33.4 % (95% CI=28.6-39.0) in 2019, chi-square p-value <0.0001 (Figure 2).

Factors associated with immediate postnatal care utilisation

In the bivariable analysis, residence, maternal education, household wealth index, number of children, place of delivery, mode of delivery, and number of antenatal care visits were variables that had a significant association with immediate postnatal care utilisation. However, after adjusting for other variables (multivariable analysis), only place of delivery, mode of delivery, and antenatal care visit showed a significant association with immediate postnatal care utilisation (Table 3).

Women who had their most recent childbirth in a health facility were less likely to receive a postnatal check within 24 hours (adjusted odds ratio, aOR=0.04; 95%CI=0.02-0.07) compared to those who gave birth outside health facilities. The odds of immediate postnatal care utilisation were higher for women who gave birth by caesarean section (aOR=4.39; 95% CI=2.28-8.46) compared to those who had a vaginal birth. Furthermore, compared to those who had no antenatal visit during the pregnancy of the most recent child, women who had less than four antenatal care visits (aOR=3.33; 95% CI=1.77-6.24), and those who had greater than and equal to four antenatal care visits (aOR=7.19; 95% CI=3.80-13.56) were more likely to utilise postnatal care within 24 hours after childbirth.

DISCUSSION

This study indicates that immediate postnatal care utilisation in Ethiopia follows a significant increasing trend from 6.4% in 2011 to 16.3% to 33.4 % in 2019. We also show that other maternity healthcare services use improved substantially between 2011 and 2019. The percentage of women who give birth in healthcare facilities increased from 11.5% in 2011 to 36.2% in 2016 to 54.0% in 2019. Likewise, the percentage of women who had four and more antenatal care visits increased from 17.3% in 2011 to 33.3% in 2016 to 44.0 % in 2019.

The consistent increase in utilisation along the continuum of maternity care services might reflect the collective impact of maternal health programs in Ethiopia. In the Health Sector Development Program IV (2010/11-2014/15) and the Health Sector Transformation Plan I (2015/16-2019/20), the government focussed on strategies to improve the accessibility of maternal health services, expansion and standardisation of health facilities, continuous quality improvement, and engaging community in planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation, and resource mobilization for the health sector.22,41 In addition to the government, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) contributed to this progress. For instance: the “Last 10 kilometres project” was implemented since 2008 by John Snow Inc. (JSI) with funding from Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in four of the most populous regions of the country, Oromia, Amhara, Tigray, and Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples (SNNP). The program’s aim is to improve the health status of families and communities through innovative and evidence-based Reproductive, Maternal, New-born, and Child Health (RMNCH) interventions.42,43

Our study also evaluates factors associated with immediate postnatal care utilisation. We show that women who had their most recent childbirth in a health facility were less likely to utilise postnatal care within 24 hours compared to those who gave birth outside health facilities. This result is in contrast with other studies conducted in Ethiopia and other sub-Saharan countries.32,37–39,44 The reason for this association is not entirely clear. It could be that women who gave birth outside health facilities needed to be referred to a healthcare professional soon after childbirth to manage complications and therefore got more attention since the deliveries were possibly conducted in a non-sterile environment. This could also be an indication of negative quality of care in health facilities as a result of staff shortage, and/or early discharge from health facilities due to crowding, contributing to inability of healthcare workers to provide timely routine checks.45

The odds of immediate postnatal care utilisation were higher for women who gave birth by caesarean section compared to those who had a vaginal birth. This result is in line with studies conducted in Ethiopia, Uganda, Sierra Leone, and Malawi.31,33,35,37,39,40 Women who give birth by caesarean section are at higher risk of short and long-term complications compared to vaginal birth, and require specific packages of care including ambulation, checking wound healing and monitoring for infection.46 For this reason, health professionals might give more attention to these women.

Furthermore, compared to women who had no Antenatal Care (ANC) visit, women who had less than four antenatal care visits and those who had greater than and equal to four antenatal care visits were more likely to utilise postnatal care within 24 hours after childbirth. This result is consistent with a study conducted based on the Ugandan DHS.31 A possible explanation could be that during ANC visits women and their families receive counselling and health education, so these women might receive education about the benefits of postnatal care services.47 In addition, women who seek ANC already show positive healthcare-seeking behaviour which might be reflected throughout the entire continuum of maternal healthcare.48 This positive association highlights the importance of early initiation and appropriate use of antenatal care services to have impact on utilisation of immediate postnatal care.

Strengths and limitations

The study used representative nationwide data which were collected after a rigorous sampling procedure. Although the DHS survey include women who had a live birth within five years before the survey, we restricted the analysis to the women who had a live birth within two years before the survey to minimize recall bias. To identify the determinants of immediate postnatal care utilisation, only those variables that were included during the 2019 EDHS were considered, which could be a limitation of our study. Relative to the full DHS surveys, the mini-DHS includes a smaller number of variables. Thus, we were unable to test other potential factors associated with immediate postnatal care utilisation. Additionally, the DHS do not collect information on complications which are known to play an important factor in use and provision of immediate postnatal care. Moreover, we could not include the 2014 mini-EDHS, since the data is not available on the DHS program website (https://www.dhsprogram.com), however, we believe that the 2016 EDHS could show the change in immediate postnatal care utilisation between 2011 to 2016.

CONCLUSIONS

The study showed consistent improvements in immediate postnatal care utilisation between 2011 and 2019. Despite the progress, the coverage remains low in Ethiopia, only reaching one-third of those who need it. Likewise, the percentage of women who give birth in health facilities and women who have four and more ANC visits increased during these same periods, however, nearly half of the women give birth outside health facilities, and more than one-fourth of women are not receiving ANC care during pregnancy. More tailored and context-specific efforts across the continuum of maternal health care services are needed to improve the utilisation and quality of postnatal care. Moreover, healthcare professionals should provide quality and timely postnatal care to all women giving birth in health facilities regardless of the mode of delivery.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Measure DHS for making data available and accessible for the study. We would like to extend our sincere appreciation to the Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM), Belgium for organizing and providing a workshop on “Write your paper based on DHS data on reproductive and child health” which the corresponding author was part of, and to Tom Smekens who provided statistical support for the data analysis.

Ethics statement

The DHS received government permission and followed ethical practices for the primary data collection including asking for informed consent from each participant and assuring confidentiality by omitting names and any personal identifiers. Permission for our secondary use of data was sought and received from the DHS Programme. We did not require a separate ethics approval to analyse these secondary datasets.

Data availability

The data used in the study can be requested and downloaded from https://www.dhsprogram.com

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Authorship contributions

AMH conceptualised the study, analysed the data, and wrote the draft manuscript. AS assisted the data analysis and reviewed the manuscript. JLB, BT, ÖT, and DEG critically reviewed the paper and gave valuable feedback. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure of interest

The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and disclose no relevant interests.

Correspondence to:

Abdulaziz Mohammed Hussen MSC, MPH

PhD student at Julius Global Health, Julius Centre for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Centre Utrecht, Utrecht University, The Netherlands

Lecturer at the Department of Midwifery, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Samara University, Samara, Ethiopia

[email protected] / [email protected]