The Mfangano Community Health Field Station represents a training and research collaboration between the University of Minnesota in the United States, Maseno University in Kenya, and a community-based organization on Mfangano Island called the Ekialo Kiona (EK) Center. Since 2010, this collaboration has implemented a series of health, agriculture, and livelihood interventions on Mfangano Island alongside longitudinal community-based research. A trusted health information source in the community, the EK Center is a community-owned initiative that has served as an administrative hub for numerous community education campaigns focused on issues such as HIV/AIDS, childhood nutrition, sanitation, obstetric emergencies, and other health concerns facing this remote population.1 Uniquely, the EK Center also features a local radio broadcast studio, home to EK-FM Suba Radio Station, an important platform for local community health education programming.

In 2019, our collaboration initiated the MOMENTUM Study (Monitoring Maternal Emergency Navigation and Triage on Mfangano), a rolling cohort study to assess barriers and delays faced by families seeking emergency obstetric and neonatal care at 9 remote health centers on Mfangano Island.2,3 Ongoing data collection was interrupted however in March 2020 with the emergence of the initial COVID-19 surge. In response, our group shifted from research activities to focus on supporting a locally tailored COVID-19 education campaign. Later in 2021 with the onset of the Delta surge we reactivated the education modalities and designed an additional vaccine mobilization campaign.

The target population for this program included the island communities of Mfangano Island Division (including Mfangano, Remba, Takawiri and Ringiti Islands) with a total population of approximately 26,000.4 Residents of Mfangano live in remote fishing villages that accessible from the mainland only by a 1-2 hour boat ride, and face considerable poverty and health challenges.5 Mfangano Island Division is served by a fragmented network of under-resourced health facilities, and remains one of the most HIV-impacted population on the planet with approximately 25% of the general population infected,6 making this community especially vulnerable the impacts of COVID-19.

Here we describe the design processes and rationale behind our chosen COVID-19 education strategies, basic outputs, and perspectives from local staff regarding strengths and challenges. It should be noted that this report is not intended to provide quantitative or qualitative evidence regarding the efficacy of a COVID-19 intervention. This report is limited by the inability to compare outcomes with a similar control population, as our group was not resourced to implement an evaluation of this scope. Moreover, as we have articulated in our recent publication, Rethinking our Rigor Mortis,7 our work on Mfangano is grounded in emerging “slow research” methodologies8 that prioritize local adaptivity, place-based commitment, and inclusivity. While our experience may not apply broadly to all rural populations in sub-Saharan Africa, we assert that global health implementation has been restricted by an overemphasis on specific types of research methodologies that lend themselves more readily to generalizable conclusions, systematic reproducibility, and quantitative analysis. As such, we believe that our groups experience responding to COVID-19 in Western Kenya provides insights and lessons that could be selectively adapted and incorporated by other place-based research enterprises facing unanticipated public health threats.

PROGRAM DESIGN

The initial Mfangano COVID-19 Response Program was designed to address community member concerns including lack of accurate health information, frequently changing guidelines, and confusion and fear among the Mfangano Island population amidst rapidly rising caseloads in Western Kenya. The program relied heavily on remote collaboration, local leadership, frequent team meetings and responsive communication between our international and local teams. Later in 2021 with the onset of the Delta Surge and as vaccines became available, we also identified a need to mobilize community leaders specifically to promote vaccine uptake.

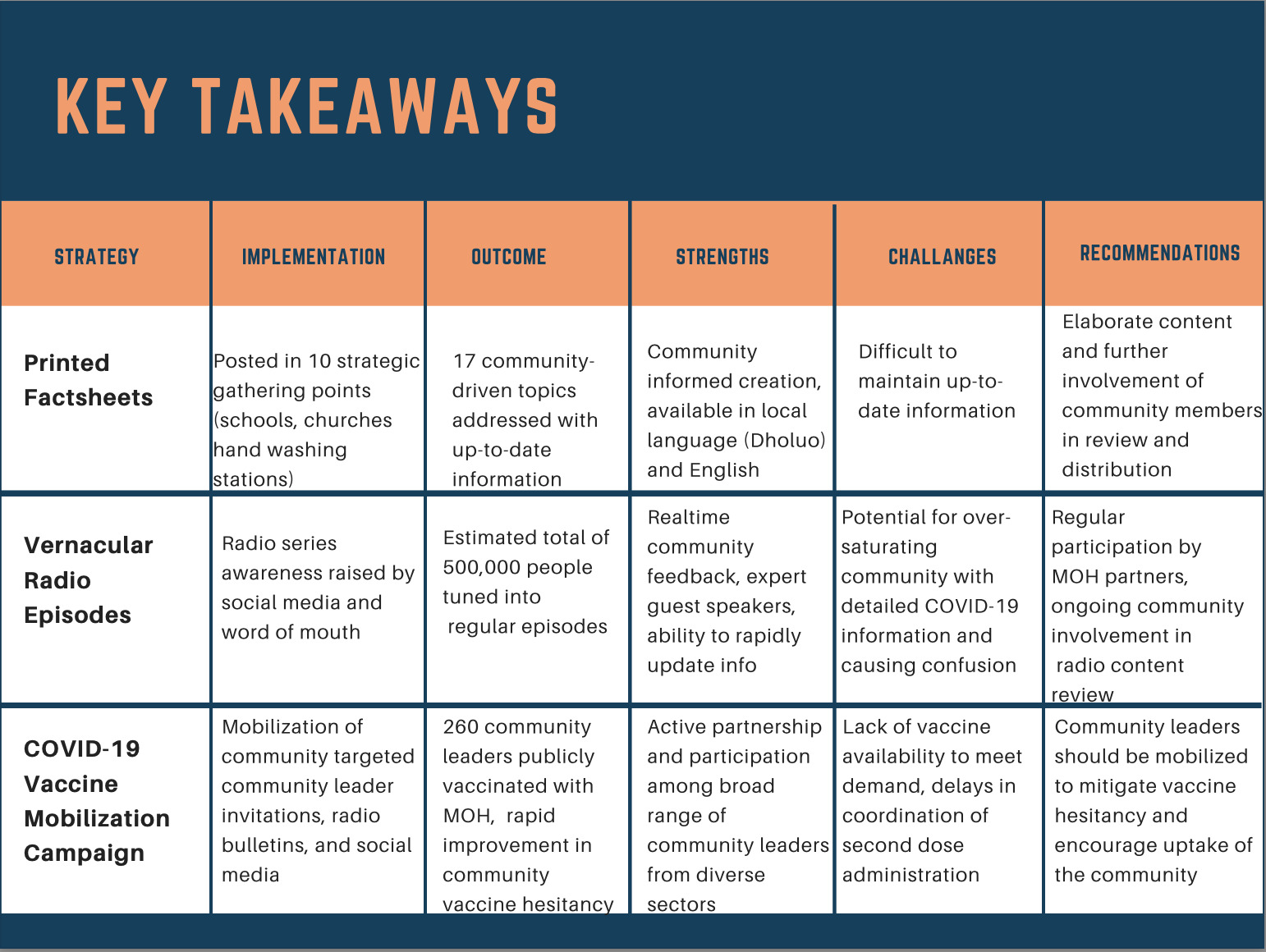

Based on prior experience and local feedback, we initially identified two parallel strategies for community education and engagement: 1) printed factsheets for local distribution at high-frequency community meeting points, and 2) vernacular radio broadcasts on the local EK-FM radio station. In addition to these primary education modalities, we supported a network of community handwashing stations that were maintained by local Health Navigators previously involved in maternal health programming through EK Center. We also supported the local MoH in obtaining PPE including masks, gowns, gloves, and sanitizing solutions. In 2021, we developed an additional strategy: 3) targeted vaccine mobilization through community opinion leader outreach. These 3 primary strategies are summarized and described further in Table 1.

Community education: factsheets and radio programming

Awareness of the program was raised through the EK Center social media channels, word of mouth, SMS messages to local health workers, and EK-FM announcements. Specific topics for education and dissemination were identified through a participatory process involving a working group of local EK Center staff, community health volunteers, MoH officials, and international investigators. In addition to input from this working group, topics were adapted based on continuous community feedback through word of mouth, on-air EK-FM call-ins and surveys, and social media. Based on this adaptive format, factsheets and radio programming were developed address the following 10 community-driven topic areas in sequential order.

-

Covid-19 Containment measures: Prevention of COVID-19, handwashing, and social distancing.

-

Exposure, isolation, and treatment of COVID-19

-

Home Based Care for sick people with COVID-19

-

Preventing stigma from COVID 19 and domestic violence during lockdowns

-

Addressing common COVID 19 misconceptions and myths

-

Strengthening the health sector to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic

-

Mfangano Health Navigation Ambulance Boat protocol for COVID-19 transfers

-

COVID-19 vaccines and accessibility.

-

COVID-19 variants

-

Importance of receiving the COVID-19 vaccine as scheduled.

For each topic, printed factsheets included pertinent graphics and culturally relevant language. Factsheets were reviewed by the local MoH and printed in both English and Dholuo. These factsheets were then given to local community health workers and Health Navigators who posted them in highly visited areas of the community, such as churches, beach offices, markets, schools, chief’s barazas, and hospitals. Handwashing stations were identified as highly trafficked locations, with over 73 users per day on average, and ideal for factsheet posting. In total, 13 factsheets were designed and distributed in 2020, and subsequently 7 more to address emerging topics, namely vaccines and variants, in 2021. All graphics utilized were public domain clipart, free from copyright, and freely available on the internet. Websites for all information sources were also listed on each of the factsheets. All factsheets were printed and maintained at locations across Mfangano Island. Subsequently, these sheets were endorsed by the US Embassy in Nairobi and made accessible for national dissemination. Please see Online Supplementary Document, Appendix I and II for examples of printed factsheets.

For each topic, a corresponding radio script was also created and included in the regular programming of the EK-FM radio station multiple times throughout the week. Radio programming was delivered in English, Dholuo and Suba languages. Programming also featured expert guest speakers including public health specialists from the University of Maseno and MoH representatives. An estimated 200,000 people around Homa Bay County and beyond tuned into the radio episodes. It is worth noting that the EK-FM radio station reaches populations beyond Mfangano Island which accounts for the high participation rate in the radio programming. Please see Online Supplementary Document, Appendix III for example of radio program script.

Vaccine promotion

In addition to these educational measures, a COVID-19 vaccination mobilization campaign was initiated in 2021 with the goal of encouraging local leaders to get vaccinated to demonstrate safety and efficacy of vaccines. Importantly, local staff communicated to community partners that the EK Center was not coordinating a mass vaccination campaign, but rather facilitating vaccination efforts with the local MoH for key leaders and vulnerable community members in order to promote future vaccination uptake. Due to national vaccination guidelines and limited resources, vaccination mobilization was focused on EK Center staff, the Suba Council of Elders, key community leaders, and vulnerable community members. EK staff members invited local leaders to scheduled vaccination sessions at the EK Center by utilizing long-standing existing relationships with the local government, the Suba Council of Elders, Beach Management Units, and the local MoH. Community opinion leaders included church leaders, Suba Council of Elders, village elders, teachers, beach management union leaders, traditional birth attendants, and health care workers. Local MoH staff traveled to the EK Center, a trusted community site to administer all vaccines. Ultimately all 23 EK staff members were fully vaccinated with AstraZeneca, and 227 against the initial target of 200 community opinion leaders were fully vaccinated with Moderna.

LOCAL PERSPECTIVES: Strengths

According to the local leadership team, it was the community-informed approach that contributed most to the sustainability of the COVID-19 program. Most of the ideas and topics of concern came from the community expressing needs as at the time of implementation. In response, the implementation team was able to address concerns in real-time using daily radio updates, one-on-one dialogues with community leaders, and regular communication from health facilities taking part in the COVID-19 response.

According to local staff on the ground, the main strengths of the Mfangano COVID-19 response program were based on the community-driven approach supported by virtual, interdisciplinary collaboration from the international team. Local staff at the EK Center led all aspects of the program design and implementation. EK staff also coordinated the relationship with MoH, allowing them to obtain up-to-date statistics and reports regarding local COVID-19 transmission and new guidelines. Frequent Zoom meetings, WhatsApp discussions, and responsive communication in both directions were essential in creating timely and accurate content as both international and local guidelines and recommendations evolved. Despite distance and virtual interactions, the friendship that emerged between Kenyan and U.S. graduate students, Kenyan and U.S. physicians, and EK Center staff in Mfangano Island created a strong alliance that allowed the team to respond and adapt to the needs of the community at each stage of the COVID-19 response. The ability of the team to rapidly gather English-language information from multiple sources, quickly translate these materials into local Dholuo dialect, and then prepare both printed and spoken word content, ensured maximum accessibility and outreach. Large numbers of community members were reached with the translated posters, WhatsApp messages shared to the EK staff and radio broadcasting team. Instant feedback shared by the community about the COVID-19 responses, could be addressed quickly, since the local staff had wider understanding of how they were implementing the responses on the ground. With detailed understanding of community cultural practices, the local staffs were able to reach many persons with accurate information and interventions in response to the pandemic.

Regarding vaccine mobilization, the inclusion of prominent community leaders was especially important. Through targeted outreach by EK Staff, local Suba Council of Elders representatives, religious leaders, and other civic leaders agreed to publicly endorse vaccinations and received the vaccines themselves. As a result, community opinions regarding vaccination rapidly shifted and demand increased exponentially over the course of a few weeks. In the end, these targeted invitations proved to be one of the simplest but most effective aspects of the program. The EK Center staff took the initiative of being the first persons to be vaccinated on the island, to communicate the next steps which the community should take. In addition, the local staff, in connection with the MOH and with support from the US-based team, created a sustainable model which ensured availability of vaccines at the EK center. Further, the local staff were able to influence the community to best participate in the vaccination program, because of their good networking and rapport with the community.

The Mbita sub-county MOH helped in review of episodes and factsheets. They also availed vaccines and staff for administration of those vaccines. Further, they provided a call center number for coordinating/reporting covid -19 suspected cases and getting other related information.

LOCAL PERSPECTIVES: Challenges

Regarding the distribution of accurate information about COVID-19, a major challenge of this community response program was the constant change in COVID-19 guidelines and the need to quickly update the factsheets that had previously been distributed. Thus, each printed factsheet was ultimately paired with ongoing radio episodes in an attempt to ensure that out-of-date printed information could be addressed through other formats. Radio episodes were continually updated as new information was available. Another concern was the possibility of creating confusion by adding more information to an already saturated topic that may conflict with misinformation circling in the community.

During program implementation, a knowledge gap became apparent within Mfangano Island Division, with the communities on East and South being more knowledgeable about COVID-19 than the remote West and North communities. This was because of the existence of Health Navigators in East and South who could provide in-time response to concerns at the community level. Lack of understanding of the COVID-19 information presented may have exacerbated existing disparities. Some community feedback did indicate confusion from this educational material, particularly related to COVID-19 vaccines. To mitigate this confusion, EK-FM provided opportunities for community members to provide feedback or ask questions about the information being shared.

Furthermore, remote coordination and the need to connect with MoH frequently presented a challenge in how quickly the team was able to develop educational materials. Local travel restrictions created challenges for coordinating the distribution of materials. Consequently, copies of factsheets did not reach all targeted areas and fewer numbers of factsheets were distributed than initially planned. This was the result of limited resources available to facilitate the program, and the inaccessibility of some areas. It is worth noting that most of the information on factsheets could only be read by literate members of the community, underscoring the importance of additional pictorials that could be easily internalized by those who could not read English or Dholuo, as well as corresponding radio episodes that could be understood by all.

In regard to COVID-19 vaccine promotion, local staff initially reported high levels of confusion, fear, and hesitancy among participating communities regarding vaccination. However, through targeted invitations, hundreds of local community leaders agreed to be publicly vaccinated to promote safety and uptake. The success of this effort created an unintended challenge in that local demand for vaccines quickly exceeded the available MoH supply on Mfangano. Although it was communicated that the EK Center was not coordinating mass vaccination efforts but helping MoH with their vaccination efforts of key leaders and vulnerable populations, many community members were frustrated with their inability to receive a vaccine. As more and more community members were encouraged to get vaccinated, it became difficult to clearly communicate with the community why the EK Center was not able to coordinate vaccinations for everyone on Mfangano Island. Community members had difficulty understanding why they needed to go to other local MoH facilities to schedule vaccination appointments when others could be vaccinated at the EK Center. There were also challenges of sustaining functional hand washing facilities at the community level in ensuring security and continuous supply of water and soap. In addition to that, based on high poverty index within the Island, over expectations of continuous supply of reusable nose mask to the community which EK couldn’t sustain because of limited budget.

Ultimately, EK staff and Health Navigators were able to provide information and resources on active MoH locations where community members could go to receive a vaccination when eligible.

DISCUSSION

Like many other community-based research collaborations around the world, our team faced considerable disruptions to our research agenda with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, given a decade of experience conducting community-based research among the island communities of Lake Victoria in Western Kenya, we also recognized that our team was uniquely positioned to respond, and thus had a responsibility to support local COVID-19 education and mobilization efforts in this remote population. This transformation required a conscious effort to pause our formal data collection agenda, and together focus on an adaptive information dissemination and resource coordination campaign. By focusing on culturally relevant written and spoken modalities, we were able to support our community in a time of need with up-to-date information. We were also able to catalyze a rapid shift in perceptions regarding COVID-19 vaccination through targeted outreach to our network of community leaders.

Given the highly specific nature of our locally tailored programming, as well as the inability to compare outcomes with similar control populations, it is not possible to draw definitive conclusions regarding the efficacy or broad generalizability of our approach. At the same time, we highlight several aspects of our program that hold valuable lessons for similar rural communities facing COVID-19 surges, including enthusiasm for vernacular radio and integration of community leaders into vaccine mobilization efforts. Ultimately, for our group, the pandemic conditions led to a reorganization of priorities, engagement strategies, and management structures, that had a positive impact on our partnership and wider research mission. Moreover, as global health partnerships around the world likely to be tested in the future from recurrent COVID surges and other emerging public health threats, it is critical that we continue to reexamine how we can harness these experiences to resharpen organizational focus, eliminate unnecessary and vestigial decision structures, and meet the moment for communities in need.

Despite the myriad public health and economic problems generated by the novel coronavirus within the communities we serve, our group was also surprised to recognize several positive outcomes for our collaboration as a result of the pandemic. Above all, we appreciated the ways in which the pandemic disrupted our normal “chain of command” and decision tree, creating new opportunities for empowerment of local research staff as primary intervention designers and executive decision-makers. While capacity building has long been an explicit goal of our group, the pandemic necessitated and accelerated a pragmatic shift, enabling our group to more fully walk the empowerment talk. As we look forward to a return to travel and face-to-face collaboration, we remain committed to sustaining these crucial transformations. This experience has reminded us that community-engaged scholarship requires an evolving reassessment of priorities, the ability to adapt to the community calendar in real-time, and a commitment to harness the hard lessons learned through crisis towards a more equitable partnership.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all our community and international partners who supported this Mfangano Community Health Field Station effort, including the Ekialo Kiona Center and Research Department staff and volunteers, the Organic Health Response Board of Directors and staff, the Community Health Volunteers of Mfangano Island, and the EK Community Advisory Group. We thank the Kenyan Ministry of Heath staff, and all Mfangano Island community leaders for their partnership over the years. The Ekialo Kiona Center would like to thank all local and international partners who have supported the Ekialo Kiona Radio Station and Health Navigation programs which helped coordinate this effort, particularly the Improving Chances Foundation and Craig Newmark Philanthropies. We would also like to thank our collaborators at the University of Maseno, the University of Minnesota Center for Global Health and Social Responsibility, and Humphrey School—Masters in Development Practice Programs. We want to acknowledge the University of Minnesota and University of Maseno ethical review committees who provided IRB approval for the MOMENTUM study associated with this report. The authors declare that there are no competing interests with regard to this report.

Funding

None

Authorship contributions

All authors contributed to the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available upon request from the corresponding author), and declare no conflicts of interest.

Correspondence to:

Charles Salmen, Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota, USA. [email protected]