Globally, the proportion of the population aged 65 years or older) is steadily increasing.1 In December 2020, the United Nations general assembly declared 2021 – 2030 the decade of healthy ageing, emphasising the need for the physical, psychological and wellbeing of older adults to be prioritised.2 Healthy ageing enables older individuals to continue contributing to society both socially and economically.3,4

Psychosocial factors, including a person’s optimism, were shown to promote healthy ageing5 and increase resilience.6 In its simplest sense, optimism, is “anticipating good”,7 whereas in scientific literature many theories of optimism/pessimism have been proposed. Two main theories of optimism prevail; attributional optimism, which refers to the unique way in which an individual explains the causes of both positive and negative events,8 and dispositional optimism which describes a relatively stable facet of personality, whereby an individual has globalised, positive future expectancies.9–11 The conceptual model of optimism as a disposition explains that optimism is a generalised expectancy of things to work out favourably and that optimism is a relatively stable facet of an individual’s makeup though it may vary situationally and across the life trajectory.9,10,12,13 Optimism is only partially heritable (approximately 0.25),14 with trait and state components,15 but also environmental effects that play a role in shaping optimism. Greater optimism is a psychosocial determinant promoting longevity and quality of life in older adults.3,11,16 Older adults who are more optimistic have a lower risk of premature mortality17 and cardiovascular disease,18 and are more likely to engage in healthy lifestyle behaviors.14

Optimism can influence how a stressful event affects an individual via appraisal of a situation, reducing or heightening stress levels, and coping style.19 The advent of the novel coronavirus, coronavirus disease (COVID-19) global pandemic brought unprecedented challenges. Older age was identified as the most significant risk factor for COVID-19 mortality.20 The pandemic resulted in the obvious ramifications for older adults’ physical health (for individuals exposed to the SARS-CoV-2), but additionally, the mental health consequences21 following the threat of the virus and subsequent restrictions imposed.

While theories of optimism have been proposed, and the relationship between optimism and the impact of significant stressors has been investigated previously,22 there is paucity of qualitative research on optimism. Our study seeks to describe optimism, explore how optimism may change throughout the life-course, and also investigate the lived experience of a stressful event, the pandemic, and whether optimism was affected.

Methods

Study design

A rich description of what optimism means to older adults has not previously been reported, so we used a qualitative design to achieve this. We used a phenomenological approach to understand the meaning of optimism and explore in depth the lived experience of the pandemic and its effect on optimism in older adults in Australia.23 Interviewing participants allowed for flexibility while ensuring rigorous data collection.24 Questions asked in the semi-structured interviews were initially developed based on the revised Life-Orientation Test,25 though in this study, no quantitative data was collected, apart from the demographics of participants. Semi-structured interviews were used to co-create meaning with the individuals interviewed.26 We conducted thematic analysis of the interview transcripts and explored our results reflecting on the conceptual model of optimism as a disposition.

Participant selection

Purposive sampling was used. Eligibility criteria were community-dwelling, relatively healthy older adults (≥65 years of age) living in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic from mid-to-late 2020. The screening included asking whether prospective participants lived in Australia during mid to late 2020 and if they were undergoing treatment for any medical or psychological conditions (if so, what their current health issues were). After screening, all eligible individuals were included in the study.

Due to pandemic-related physical constraints, recruitment took place via the social media platform Facebook. Based on a consensual decision among the authors, Facebook was deemed suitable given its’ popularity and accessibility to older individuals. No individuals were directly contacted to participate in the study. The Facebook post was approved by the MUHREC (Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee) before being posted on a unique page. The post was controlled, so individuals could not ‘tag’ other individuals who might not wish to participate or for their characteristics and/or identity to be made public, though readers could ‘share’ the post to disseminate the information. The post included an email address for the lead author and a Monash University phone number. No prospective participants were under any obligation to take part in the study. Additional conscription took place via word-of-mouth through Monash University colleagues and their personal networks, with interested individuals providing the email address and/or phone number to directly contact the lead author. Recruitment led to all eleven potential participants being included in the study and completing the interview.

Study Participants

The participants’ characteristics are outlined in Table 1. The sample consisted of five males (45%) and six females (55%), aged between 68 years and 74 years. The majority lived with a spouse, were retired or semi-retired, and had at least a secondary school level of education. There were almost equal proportions of those who lived in metropolitan (45%) and regional areas (55%) of Australia.

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim by the lead author and checked for accuracy by the last author before analysis. To explore the data, reflexive thematic analysis was employed, drawn from the work by Braun and Clarke,27,28 while applying the theory of optimism as a disposition9,10 to form the overall conceptual basis for the study. Following the reflexive thematic analysis framework,28 six phases were moved through recursively. The first author completed open coding for the entire dataset. Then, all codes were collated and discussed between authors, and relevant data extracts were noted before generating initial themes. Themes were generated inductively, from the raw data, as well as deductively based on the conceptual model of optimism as a disposition.9,10,25,29 A coding tree was used to develop themes and sub-themes, which consisted of a framework that hierarchically organised the 425 codes, with categories and sub-categories of codes, exploring and highlighting interdependencies and relationships (see supplementary materials 3). Themes were reviewed by checking against the codes and collated data, then further refined until authors reached a consensus on the final themes, sub-themes, and exemplar quotes from the transcripts. Data were organised using the NVivo Version 20 (QSR International, 2020) software.

Ethics considerations

This study was reviewed and approved by the Monash University Research and Human Ethics Committee (reference number: 25833). All participants provided their informed consent, verbally, prior to taking part in the study.

Results

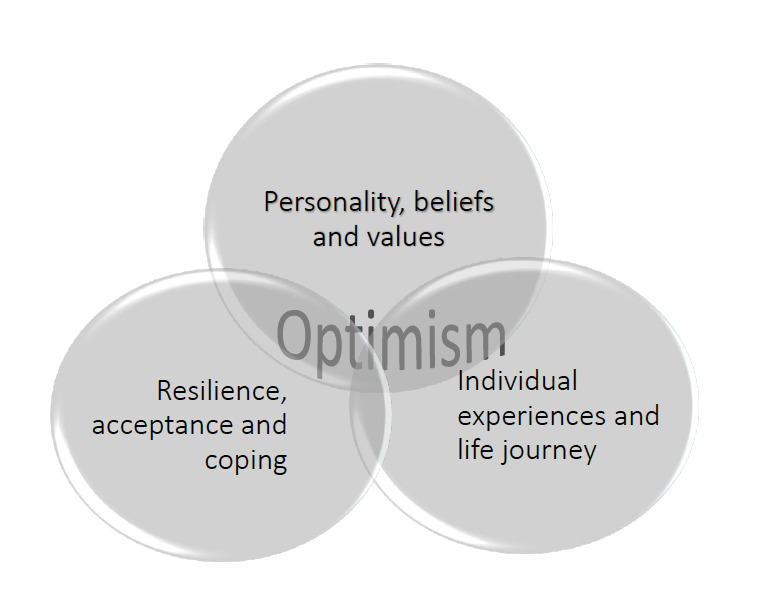

Thematic analysis resulted in the generation of three main themes, and nine sub-themes. Table 2 describes the themes and sub-themes emerging from the analysis and illustrative quotes chosen. From our analysis of the data, we summarised the dynamic interactions between personality, resilience, acceptance and coping, and individual experiences in shaping the optimism of individuals in the study (Figure 1).

Theme: The essence, beliefs and core meaning of optimism

The first theme provided a rich description of optimism and the unique understandings of optimism. Participants described what they thought optimism was and the factors influencing its development.

Sub-theme: Perception of optimism and its’ connotation

All participants described how they perceived and understood optimism, and when asked if they thought of themselves as optimistic overall, all agreed. Participants described optimism as a generalised, “all-encompassing” attitude, feeling or outlook. Some specified that they were a ‘realist’ or ‘not’ a pessimist, and others described their perception and beliefs about pessimism.

“Waking up each morning, and looking forward to the day” - P11, male 73y.

“I feel like I’m a mostly optimistic person though I realise that some people, a lot of people, aren’t like that” - P9, female 69y.

Sub-theme: What shapes optimism – genetics, and family history

Several participants believed that optimism had genetic origins or resulted from family history. Historical context for this generation appeared to be implicated, with their parents having lived through wartime. Some participants said they were optimistic like one of their parents or relatives, and others acknowledged that one of their parents was not optimistic, and they had learned from this.

“In our extended family, I think everybody was very optimistic” - P7, female 69y.

“My father always says any problem is so small compared to what he went through in the Dutch resistance” - P5, female 68y.

“I do think maybe you’re born, genetic wise… my mother was not optimistic” - P4, female 68y.

“I’ve learned a lot from both of them… And I think that’s a good thing” - P2, male 74y.

Sub-theme: What shapes optimism – gratitude and hopefulness

For most individuals, being grateful and hopeful helped shape their optimism. Participants spoke of being appreciative, not only of the material things in life but for their capacities, the world around them, and valued relationships. Two participants spoke specifically about being hopeful and one highlighted being lucky in life, which contributed to their optimistic behaviour.

“I’m very grateful. For life. I just think, “I can’t complain”. I’m ageing, but I’ve got a wonderful partner, wonderful family. I live in paradise” - P5, female 68y.

“I am a very hopeful person… my hope is actually buoyed up by what I do” - P8, female 68y.

“I think I’ve been lucky in life” - P4, female 68y.

Sub-theme: What shapes optimism – life-course development and life journey

Almost all participants talked of experiences through life that had shaped their personality and optimism. Relationships, notably with their spouse and/or family, played a role, as did their professional background and working life, their physical health, and wellbeing. For some, the process of ageing had contributed to their attitudes, and lifestyle (e.g., hobbies and interests, keeping active, and maintaining social connections) also contributed to their experience and personality. For several participants, the location in which they lived (such as the beachside or in the hills) affected their outlook on life. Similar numbers of participants described that their optimism had either been consistent across the lifespan or had varied over time. Maturation was important, and one man spoke of how his perspective had changed with age.

“I have been through numerous episodes over my life, and they have always come to the fore at the end” - P2, male 74y.

“It’s all relative, I think. A bit where you are in life” - P5, female 68y.

“We don’t tend to look back much. I think that before, you probably reflected on the past more. Now, we don’t” - P2, male 74y.

Theme: Personality and disposition shaping optimism through a life course

This theme explained how optimism was apparent in the participants, reflecting the individual differences common to those who are generally optimistic.

Sub-theme: Pragmatic beliefs and attitudes

A number of the participants described ‘matter of fact’, pragmatic beliefs and attitudes. One spoke pragmatically about the course of history and mankind. An overall concept that arose was to ‘not worry’, to ‘take action’ and just 'get on with things. Some participants indicated planning ahead and taking action, being practical when facing potential problems, and agency.

“Humans have not changed” - P5, female 68y.

“As I said, if things go wrong, well, um climb back on the horse and get over it” - P6, male 73y.

“Well, first of all, you’ve got to deal with it” - P5, female 68y.

“So, it sort of, a lot of that depends on yourself, too” - P6, male 73y.

Sub theme: Solution-focused behaviors and attitudes

Participants described seeking to find solutions and behave in accordance with the fact that a resolution could be found. Participants spoke of being prepared for things that could go wrong, and working things out by problem solving. One participant described herself as practical, while another spoke of seeking support to cope with difficulties. Some participants alluded to foresight, predicting upcoming difficulties and subsequently being strategic, adaptive and creative.

“Somehow, try and solve it” - P5, female 68y.

“If something comes up, then you have to change. You just work around it or you, you just have to deal with it as it comes” - P10, female 72y.

Sub theme: Positivity – looking on the bright side

For all the individuals interviewed, an overall disposition of positivity was allied with optimism. They mentioned enjoyment, looking for positives, and several also discussed the connection between optimism and happiness. For most, optimism related to having upbeat expectations and keeping an open mind. For one woman, being positive provided direction. Gratitude was mentioned, as well as resilience, while for others positivity was about perception of oneself (i.e., self-esteem) or the world around them.

“Absolutely! There’s no point getting out of bed every morning if you don’t feel positive!” - P7, female, 69y.

“You walk into a room, you see the best side of the room – not, like, all the cobwebs up there” - P7, female 69y.

Theme: The effect and aftermath of a stressor - COVID-19 pandemic

The final theme emerging from the data was individual’s experiences during the pandemic, including how they managed physical and social restrictions, and how it impacted upon them personally.

Sub theme: The role of proactive coping strategies on optimism

Adaptive coping was used by most participants during the pandemic. Some sought alternatives, such as use of technology (e.g., Zoom) to manage challenging times. Routines, keeping occupied, and engaging in enjoyable pastimes helped participants cope with the stressful situation. Additionally, proactive attitudes and perspectives such as being patient, and taking necessary steps with the constraints in place, helped participants to cope. The role of individuals in the broader context of the social milieu was also mentioned. To cope, a few participants described viewing the restrictions as temporary. For others, keeping physically active and healthy also helped. Participants generally exhibited problem-focused coping, that is, they took action in order to deal with the stressful situation they faced.

“You do the best you can, don’t you?” - P6, male 73y.

“We’re doing this for the better good. For our society” - P5, female 68y.

“Ah, I could walk, so I, um, that’s what I was doing. I was walking a lot” - P4, female 68y.

“When it first became obvious that there was a good chance that we would be shut down, um, the approach that I took there was to probably take it head on” - P3, male 71y.

Sub theme: The role of acceptance on optimism during the pandemic

A few of the individuals interviewed spoke of acceptance, some with a sense of resignation. Participants discussed COVID-19 as a reality, similar to other diseases, and whilst not seeing the situation as fortunate or a pleasant one, they acknowledged that worrying would not be helpful. Participants did acknowledge the difficulties faced, such as missing out due to rules and restrictions and experiencing some challenging emotions. While conceding the many things they missed out on, such as travel and family celebrations, overall, the group accepted the difficulties faced.

“I mean, we were disappointed, um, but – again – 'cos what else are you going to do?” - P10, female 72y.

“We can’t change it” - P5, female 68y.

“It is what it is” - P6, male 73y.

“There’s a sense of nothingness” - P5, female 68y.

Sub-theme: Unique individual experiences and the shaping of the level of optimistic responses to the pandemic

Unique, individual experiences during the pandemic had both emotional effects and practical implications and consequences. For most, the COVID-19 pandemic did not appear to have affected their optimism and even gave them more hope for the future. For one individual, the pandemic made them even more resolute to fully experience life. Emotional effects included the impact of difficult emotions, such as a sense of Groundhog Day and feeling annoyed, but also helpful feelings, such as a sense of relief about certain aspects of the restrictions. Two participants spoke specifically about feeling comparatively well off, while four participants discussed the role of authorities and trust in the government. There were mixed opinions on governance and decisions made by those in leadership positions. Many individuals gave reasons for why the virus had not affected their optimism, with a few viewing the pandemic as a temporary adversity, while others had been living in areas with relatively few cases of illness. Interestingly, there appeared to be no commonality with those in highly impacted areas (e.g., metropolitan Melbourne) compared to those in areas where impact was less (such as regional communities). Nor were there other trends related to gender, education, or living situation. A couple of individuals focused on the return of ‘normality’, such as borders reopening, and others reflected on similar events in their lifetimes and how such historical circumstances had resolved.

“I expect that there will be some massive changes after this occurs, and probably, I think – mostly, most of them – a lot of them, will be to the good” - P1, male 68y.

“It’s probably… made us more determined. To do more” - P2, male 74y.

“We lost out on a few things, like not being able to go to family birthdays, and ah the socialising, dining out – those sorts of things. Travel” - P3, male 71y.

“Ah, it wasn’t good governance to start with but I think he’s done an amazing job since then” - P6, male 73y.

“Being up here and being isolated, it hasn’t impact(ed) greatly on us” - P2, male 74y.

Discussion

With the population ageing, research is needed to explore how positive health assets may improve older adult’s capacity to contribute meaningfully and enjoy a good quality of life. Theories of optimism vary, though a conceptual model of optimism as a disposition has been related to healthy ageing5 and improved quality of life in older adults.16 However, there is a lack of description of what optimism means to older adults themselves and their lived experience of optimism across the life course. In addition, the phenomenon of optimism during the pandemic has, to the best of our knowledge, not been explored, or whether lived experiences during the pandemic had an impact on optimism.

Our study explores the meaning of optimism for older Australian community-dwelling adults, how their optimism varied (or not) across the life course, and their lived experience of optimism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Semi-structured interviews were conducted via teleconference with eleven older adults (55% female) who resided in metropolitan and regional areas during 2020.There were complex and dynamic interactions between individuals’ personality and values, the ways in which they cope and their life experiences and journey.

Our first theme explained older adults’ perception of optimism and its meaning, enabling us to develop a rich description of optimism that reflected both personality and values. Participants’ perception of optimism as a generalised tendency of positivity,9 and both a hereditary personality trait and a malleable state14,15 is largely consistent with existing theoretical evidence and conceptual model of optimism as a disposition.9 Social rejection may occur for individuals who have a pessimistic outlook30 which may explain why all participants claimed to be optimistic. Perhaps interviewees anticipated judgement if they identified as ‘not’ optimistic. As evident in our results, research suggests gratitude, optimism and hope are correlated.31 We found that participants believed ‘genes’ also shape ones’ optimism, which is in accordance with endogenous theories of personality development.32 The life journey and the experiences embedded within it shaped the personality and optimism of participants, which is aligned with contextual theories of personality development.33 Some participants described changes in their optimism with ageing, and research suggests that optimism does in fact vary across the lifespan.12,13 The good health of the participants may relate to their optimism - high optimism is associated with better health, and engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviors.16

We report that personality shaped the beliefs, attitudes and behavior of participants – i.e., their optimism,34 and that their optimism was shaped by life experiences. We suggest that this occurs through a socialisation effect.35 Participants described optimism as a positive orientation, aligning with theory that optimism is an expression of a disposition of positivity.36 We report that optimistic individuals were likely to favor approach-based, problem-focused coping strategies as opposed to avoidance-based strategies.34 The participants’ optimism was associated with actively planning and problem solving, which can lessen the impact of stressors.37

For participants, their optimism served to help them cope proactively and seek solutions during the stressful period of the pandemic. Optimists have increased likelihood of remaining engaged with their goals, and life itself, in the face of hardship.38 Previous research suggests stressful situations do not preclude positive emotions in older adults.39 Our themes converged when we explored how the pandemic affected participants, reporting that their personality and life experiences shaped their individual journey and responses, including those to COVID-19. We found that the way participants appraised and interpreted challenging circumstances, e.g., viewing the pandemic as any other disease or a temporary situation, shaped how they adapted to it.39 Our interviews revealed that older adults’ sense of optimism appeared to result in low experience of fear and vulnerability, which may have been expected given the novel virus.22 Some participants described how their social context, such as where they lived and their relationships also shaped their appraisal of events.33 Participants demonstrated resilience, that is, they effectively adapted to major change in their environment and an unprecedented obstacle.40

Some of our findings were not aligned with research into the lived experience of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic overseas. Reportedly, older citizens have used faith as a source of strength and coping during the pandemic,41,42 though none of our participants discussed this. The experience of the pandemic is likely to vary according to the responses by government and public health departments.43 The lived experience of individuals during COVID-19 alerts us to the diversity of all populations, including older adults, and their experiences of stressors globally.44 Much of the published research into lived experiences of the pandemic have been conducted in the US. We suggest that a country’s culture and response to the pandemic plays an important role. For example, in a study of Malaysian older adults, ‘active’ coping was not used as a strategy,45 which is in contrast to our study and those of Finlay et al from the US.41

Our study makes a unique contribution by giving older adults a “voice”, which arguably captures a perspective on optimism not provided thus far. Phenomenology enabled us to explore the lived experiences that shape the development of personality and our reactions as we age.33 By developing a rich qualitative description of optimism, we clarified some of the historical challenges in defining optimism by exploring the complex interplay between disposition/personality, and attributional style.8 This was evidenced by the nuanced interrelationships between themes and sub themes.

Study strengths and limitations

While this study is novel and timely, we concede the limitations of our research. Using Zoom video conferencing may have excluded potential participants. However, community-dwelling adults are increasingly using technology and the internet, with 93% of older Australians having internet access at home in June 2020.46 Similarly, we only used one social media platform, Facebook, for recruitment. However, of adults 65 years and older who use social networking, 97% use Facebook.46 Thus, we feel results were not significantly impacted by the sample used. We acknowledge the risk of a selection bias in this study, and it is likely the true effect of optimism may have been over-estimated, as less optimistic individuals would be less likely to participate. Data was collected in an opportunistic fashion to coincide with perhaps the most stressful period for older Australians – many were in ‘lockdown’ or stay-at-home orders. Therefore, data analysis was not conducted simultaneously with data collection to reflexively inform the interviews. Ideally, data collection and analysis would have occurred recursively so that as codes emerged, the focus of interviews could be changed to explore codes in greater depth and detail. We maintained rigour and reduced the risk of bias as much as possible by ensuring the analysis was transparent and calculating the inter-rater reliability of the coding (78%), which demonstrated high reliability. For effective phenomenological enquiry, in-depth interviews are required, and each interview in our study lasted 25-40 minutes. Longer, more explorative interviews may have led to richer and deeper analysis. Nevertheless, the breadth of experiences and perceptions elicited are meaningful and thought-provoking. The study was not intended to be, and may not be, representative, as most qualitative research is hypothesis-generating. However, we prepared and piloted interview guide prior to data collection to minimise bias, a mixture of men and women from various locations being interviewed, and transparent data analysis, reached consensus between the lead author (HC) and senior author (ST) for all themes, sub-themes and illustrative quotes. Details for the minimisation of bias are addressed in the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist, provided in the supplementary materials.47

Implications for practice and further research

We propose that qualitative research may add further richness and depth to the current understanding of optimism. Our findings suggest that optimism is high for individuals in early old age, so exploring the perceptions and beliefs of individuals from other age groups may clarify the reasons behind the trajectory and stability of optimism across the lifespan.12,13 Prior research suggests that the experience of positive emotions may help older adults not only cope with stress, but also recover from it.39 Therefore, we suggest that future research could further explore how optimism, as evident in our sample, can help other individuals as they recover from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Further research is needed to design a way to effectively increase dispositional optimism for more than a brief period of time, though a recent systematic review48 demonstrated that a relatively simple intervention could increase optimism in the short term. Future directions may involve designing empirical tests – such as, controlling an exposure and then comparing the outcome based on an individual’s level of optimism, to further explore the role of optimism in coping with challenging experiences. Our results support the conceptual model of optimism as a disposition, influenced by our genetic makeup and our environment and life experiences.

Conclusions

In summary, our research ties together novel understandings of optimism from older adults’ perspective with what is known about personality, coping and how these affect how an individual copes with stress. We demonstrate that for older adults, life experiences shapes what they perceive optimism to be, and that their optimism influences their life journey. COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, highlights the optimism of older adults and the ways in which this enabled them to adapt and cope with the challenges that ensued.

Funding

None.

Authorship contributions

All authors contributed to study design and writing of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ (available upon request from the corresponding author), and declare no conflicts of interest.

Correspondence to:

Dr Stella Talic

School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, 553 St Kilda Rd Melbourne 3004, Australia.

[email protected]