Worldwide achievements in medicine and health are limited by shortages in healthcare delivery, especially among the most vulnerable global citizens. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), despite experiencing 24% of the global burden of disease, the WHO African Region experiences has access to only 2% of the global physician supply and spending.1 To aid such regions, high income countries such as the United States conduct about 6,000 medical mission trips each year.2

The Islamic Medical Association of North American (IMANA) is a non-profit faith-based organization that provides medical relief to people globally. One of the IMANA missions, SaveSmile, is dedicated to performing cleft surgeries on people of all ages in Khartoum, Sudan. With a global prevalence rate of 1 in 700 live births3 cleft is the most common facial anomaly in children.4 Besides the obvious impairments in eating and speaking, children with orofacial clefts also report disrupted peer interactions, poor self-image and higher levels of anxiety and shame compared with their normal peers.5 Seeking assistance due to high number of cleft cases and a lack of oral and maxillofacial surgeries and short supply of surgeons, the Sudan Islamic Medical Association (SIMA) reached out to IMANA and SaveSmile was first launched in the spring of 2009 and cleft palate surgeries were performed in Khartoum, Sudan. Since then, SaveSmile has returned to Sudan every year until 2021.

While substantial literature documents orofacial cleft surgical missions to south,6 and central7 America, and south8 and east Asia,9 to our knowledge, no studies have been reported such surgical missions in north Africa. The main objective of this report is to describe SaveSmile’s 10 year surgical mission experience in providing orofacial cleft repair procedures to children and adults in Sudan. We describe operational and surgical details and complications, while also reviewing the challenges and opportunities for conducting such humanitarian programs in similar underserved regions of the world.

METHODS

Geopolitical and Organizational Considerations

The government of Sudan authorized the Sudan Islamic Medical Association (SIMA) to collaborate with the Islamic Medical Association of North America (IMANA) and provided them medical licenses to operate the SaveSmile mission in Sudan, in 2009. At the time Sudan was led by the former President Omar Al Bashaar. After two civil wars, in July 2011 Sudan split into two nations with the northern territory referred to as Sudan and the southern parts comprising of South Sudan (Figure 1). South Sudan is a majority Christian nation while present day Sudan remains predominantly Muslim. Of note, the Al Nejood Elkhair Society, a charitable foundation, provided a bus to continue transportation of patients from Juba in South Sudan to the hospital in Sudan where the surgeries were being performed.

For the first three years, from 2009 -2011, the IMANA Save Smile mission conducted surgeries in central Khartoum in Khartoum Dental Teaching Hospital. Subsequently, the site of surgeries moved to the Khartoum Dental Teaching Hospital, a private institution, due to its superior facilities and resources. In 2020, SIMA was unable to support IMANA due to governmental financial constraint and the mission then changed from Khartoum to El-Obeid at a private hospital named Al-Ubayyid International Hospital in Eldaman.

Surgical candidates mainly came from the states of North Kordofan and West Darfur, specifically from the villages and cities of El-Obeid, Kassel, Janina, Kadaqoli, Wadi Medani, Nyala, and Sanar. Many also came from unknown villages from the regions Kordofan and Darfur. The majority of South Sudanese patients originated from Juba. The SaveSmile mission was advertised by newspaper and radio media outlets. Particularly, one radio show held by a prominent local cardiologist was able to disseminate information regarding SaveSmile, nationally on a weekly basis.

During each SaveSmile mission there have been approximately four plastic surgeons, four anesthesia personnel, two local surgeons, and eight other healthcare physicians travelling to the region. In the first year there were only 2 IMANA surgeons; one operated with patients under general anesthesia while the other surgeon used it under IV sedation with ketamine. Eventually, all cleft lip procedures transitioned to using IV sedation. All missions included a mentoring component wherein local surgeons were trained in improved anesthesia techniques novel to them in an effort to promote surgical advancement in the region.

The major barriers to implementation involve operation logistics, funding, supply procurement, and physician-patient communication. As foreigners, practicing medicine in Sudan involved clearance from Sudan’s medical board as well as special permission from the local hospital and the relevant documentation; full approval took several months. The funding for each trip (approximately $35,000-$40,000) was obtained through national IMANA fundraisers within the United States while the services of the medical staff was volunteer-based. The process of supply procurement was carried out within the US, packaged by volunteers, and transported to Sudan through the coordination and oversight of the Sudanese Embassy in the US and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Sudan. The supplies included, but were not limited to, surgical and anesthesia supplies, IV materials, and medications. Finally, the language barrier was overcome through the methods described in the perioperative procedures section of this paper.

Perioperative procedures

Each SaveSmile mission performed two types of surgeries: cleft lip (right, left, and bilateral) and non-cleft lip (palate and revisions). Patients typically completed a pre-operative evaluation by local dental hospital resent staff a week prior to surgery. They arrived at the hospital with one parent on the day of surgery and completed a registration process by IMANA team members. Using skilled translators, the surgical team explained the procedure as well as specifics regarding post-operative wound care. Surgery was performed under IV sedation or general anesthesia, depending on the complexity of the case. After the surgery, they were transferred into the recovery areas where they remain for overnight observation. Prior to discharge, the parents were shown videos in Arabic that educated them on feeding techniques and post-operative care. As the team’s experience progressed, they soon realized that pamphlets are best to give to the patients to reference in case they forgot the verbal instructions. Due to the high illiteracy rate, they were also given pictorial brochures which helped maintain the cultural competency of the care team. There are no reports of patients returning the following year due to repair failure.

The patients were encouraged to stay in the area for 2 weeks for further post-operative follow up evaluations. They were also asked to return for any noted complications.

For the first two years, only two operating rooms were present, limiting the number of surgeries that could be performed. The following years utilized four operating rooms, which is reflected in the significant increase in clefts repaired.

Data collection and analysis

The study was conducted after approval from Pearl IRB, an independent Institutional Review Board. Being a retrospective study (no new data was being collected), the study was exempt from full IRB review. Patient information was extracted by trained study personnel from the original paper copy files, under the supervision of two physicians. Several “practice runs” were done before actual data collection. Periodic meetings between the main abstractors and physicians were set up to resolve questions about data entry and classification and review coding rules. Cases were periodically sampled and reviewed by supervising attending to assess the reliability of the data collection.

Data were electronically compiled and entered in Microsoft excel, void of any personal identifiable information to honor privacy codes. Data was then processed with basic python programming and charts were generated using Microsoft excel.

Data was analyzed and sorted according to year of surgery, sex, and type of surgery. Data from 2009-2010 is in Sudan on paper files and are missing due change of command and improper care of medical records.

Results

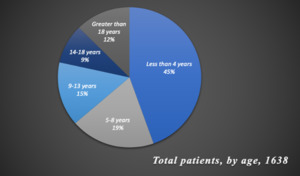

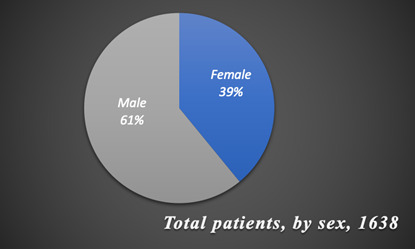

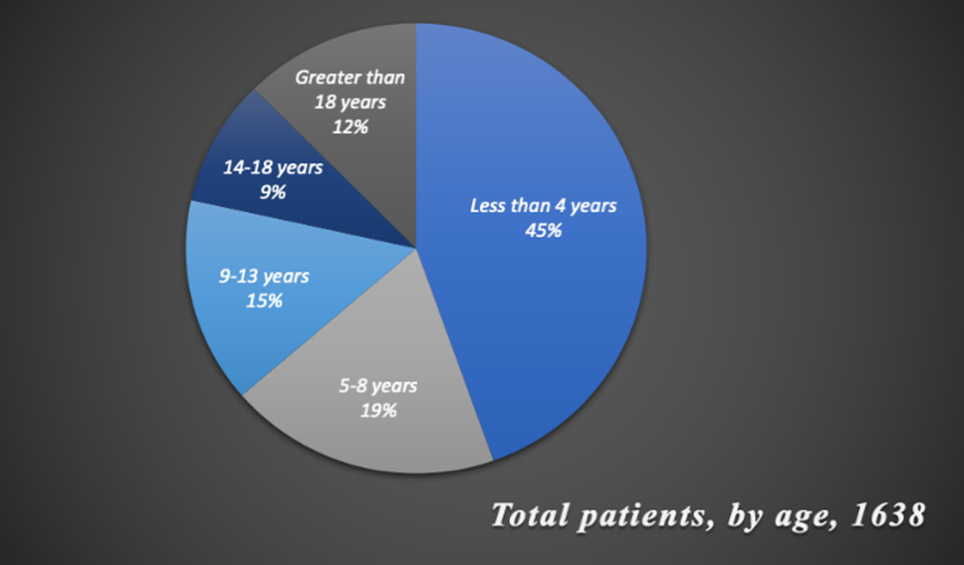

Over a 10 year period, 1638 orofacial cleft surgeries were performed by the IMANA SaveSmile mission (Table 1). Figure 2 illustrates that 998 patients were male and 640 were female out of the 1638, indicating a higher deformity rate in males than in females. According to Figure 3, most surgeries were performed on children age four and younger and the fewest number on those older than eighteen. The youngest patient operated on was three weeks old and the oldest was 63 years old. Of the 1638 patients, few cases were not cleft lip; instead, they were cleft palate revision surgeries. Among cleft lip surgeries, left cleft lip was the most common type of cleft lip deformity while bilateral was the least common.

Discussion

This paper outlines the efforts of the SaveSmile mission, over a period of 10 years, in Sudan. Surgical teams were confronted with a diverse age range and cleft type. Both initial and revision cases were operated on.

Considerable benefit to the local population can be inferred through documentation of similar experiences, in low- and middle-income countries. Efforts in maternal and child health, as well as communicable diseases, have been significant in LMICs; however, surgery is the “neglected stepchild of global health missions,”11 further highlighting the relevance of SaveSmile. Also, timely access to care is hindered by income as every 1000USD decrease in GDP per capita in LMICs leads to a 70% increase in the odds of delayed surgery.11 SaveSmile’s annual presence provided the population with the consistent opportunity to receive free care for a procedure that costs around $200USD, a price that may be prohibitive to most families in Sudan.

The benefit of cleft surgeries extends beyond functional and cosmetic effects and impacts the daily adjusted life years (DALY’s), leading to overall societal and economic prosperity. A cost effectiveness ratio (the cost for each DALY averted) of $79-$146 USD12 was determined for cleft surgery in Africa using formulas and guidelines created by the WHO. According to these guidelines, this ratio is deemed very effective as it is less than the GDP per capita.13 Cleft surgery should be considered an “essential children’s surgical procedure,”12 due to the magnitude of benefits. Additionally, those who have undergone the surgery have enhanced abilities and the opportunity to contribute as productive members of society.

Because patients of all ages were operated on during SaveSmile and no nationwide-wide data on cleft is available, neither the incidence nor the prevalence can be calculated. However, male patients outnumbered female patients by approximately 1.5 times, which contradicts data from a prior 2005 study, conducted in 3 urban hospitals settings in Sudan, where the reported male to female ratio is 3:10.14 The discrepancy in male to female ratios between the two studies may be explained by the gender disparities in access to health care, commonly seen in LMICs. For procedures that affect both males and females equally, women in LMICs have significantly lower hospital admission rates, indicating unequal access to health care. For example, the ratios of male to female admissions for emergency abdominal surgeries and general admissions are 2.2 and 1.4 respectively, whereas this ratio is approximately 1 in high income countries.15 Also, mothers from a study conducted in Malawi were found to prioritize the health and wellbeing of their sons in stressful situations, resulting in the neglect of their daughters.15 Moreover, the previously reported prevalence rate of .9 per 1000 births14 seen in Sudan in 2005 is lower than that of Europe, possibly due to under reporting cases as most births in Sudan do not take place in formal hospital settings.14

Moreover, like any large-scale project, SaveSmile also had its own limitations. The reliance on donations for both medical supplies/equipment and labor limited amount of care that could be provided. Also, there was an inability to follow-up with patients and their recovery in the long-term since this was an annual mission and patients often traveled an arduous journey for this that was difficult to repeat for follow-ups one year later. Finally, it is possible that patient age data in the year 2020 was recorded incorrectly. This is because in 2020, a minimum age requirement of five years was established by IMANA to undergo a cleft procedure. Desperately seeking care for their children, it is suspected that some parents may have misreported their children being older than they actually were.

With one of their main goals being humanitarian aid, IMANA often targets overlooked health conditions and areas of the world in attempts to alleviate their burdens of disease. Due to the scarcity of resources and surgical training, low- and middle- income countries (LMICs) struggle to provide adequate surgical care to their populations. Although one third of the world’s population resides in Africa and Southeast Asia, only 12% of specialized surgeons globally practice in those regions as many of them migrate to higher income countries16 in a phenomenon known as brain drain. As a result, few experienced physicians remain in LMICs to pass on their knowledge and expertise to newer generations of physicians. Additionally, the high out of pocket costs associated with medical care often leave people and their families in economic turmoil, further reducing their life expectancies. In fact, only 1 out of 10 people in LMICs have surgical care at their disposal.16 Thus, the need for such missions remains unquestionable.

Conclusions

The significant benefit of mission trips such as SaveSmile is evidenced by the sizeable number of cleft patients whose lives are changed both physically and emotionally. Organizations such as IMANA fulfil a critical need in such underserved populations and play a key role in training and mentoring local surgeons on the surgical techniques and post-operative care required to sustain such efforts.

Acknowledgments

We thank student interns, Rania Lateef and Quin Ray, for their dedication in chart review and meticulous conversion of paper charts to digital data. We also wish to acknowledge the team effort (medical students, residents, physicians, and nurses) that are critical to the success of every mission.

American lead team

Plastic Surgeons: Dr. Parvaiz Malik, Dr. Khalique Zahir, Dr. Irfan Galaria, Dr. Azhar Ali.

Oral Maxillofacial Surgeon: Dr. Alaa Omer.

Anesthesiologists: Dr. Ismail Mehr, Dr. Wasif Hussain, Dr. Asif Malik, Dr. Farheen Sultana, Dr. Saud Farooqi, Taqi Salam CRNA, Marium Laiq Ali CRNA.

Turkish lead team

Senior plastic surgeon: Prof. Dr. Ethem Güneren

Surgical nurse and chief of organization: Serap Arslan Odabaşı R.N.

Authorship contributions

- M.A.-Literature review, supplemental research, and writing contributions to all sections.

- R.Z.- Obtained essential information regarding SaveSmile from coordinators and surgeons and writing contributions to methods section.

- Z.Z.-Data processing, analysis, interpretation, and visualization.

- J.A.-Data processing

- T.L.-Editor of all sections.

Competing interests

The authors completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ (available upon request from the corresponding author), and declare no conflicts of interest.)