Women in sub-Saharan Africa face numerous barriers to reproductive health and antenatal care (ANC) services.1 As a result, the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) increased by over 20% between 2012-2017 in Tanzania.1 This persistently high MMR raises the question of whether the country can achieve the Sustainable Development Goal 3 target: less than 140 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births by 2030.2

A study conducted in the Dar es Salaam region of Tanzania found that although over 90% of women deliver in healthcare facilities, the quality of services provided by these facilities is substandard.3 This leads to an excess of preventable maternal morbidity and mortality.3 In metropolitan areas, such as Dar es Salaam, overcrowding at facilities, shortage of human health resources, delays in care, heavy traffic, and a limited number of ambulances all present as barriers to seeking maternal care in a timely manner.3 Additionally, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, increased demand for child caregiving and a compromised household environment also serve as significant barriers.4

A recent qualitative study asked health providers and hospital/clinic managers in Burkina Faso to list factors that contribute to improved quality of perinatal care and an increase in facility-based deliveries.4 These included leadership, strengthening relationships of trust with communities, users’ positive perceptions of quality of care, and the introduction of female professional staff.4

We sought to build on the existing body of knowledge by exploring and examining health providers’ knowledge, beliefs, and perspectives regarding individual, cultural, community, and health system-based barriers and enablers to women accessing Tanzania’s reproductive and maternal health services.

METHODS

Study setting and design

The study was conducted in Tanzania’s Geita, Singida and Singida DC districts. These study areas were purposely selected because they were the study areas for a mixed-methods implementation research program, which included a cluster-randomized controlled trial of health facilities and communities (manuscript in preparation). This examined the effectiveness of a smartphone-based intervention used by health providers and community health workers (CHWs) (manuscript in preparation). Tanzania has a very well-established volunteer system of CHWs that play critical roles in community-based health promotion (manuscript in preparation). CHWs work and live in the communities they serve, and they are considered extensions of the health system (manuscript in preparation). They work to improve recognition, diagnosis and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, while also strengthening guideline-based processes of ANC and postnatal care (PNC) in health centres and hospitals in 4 districts in Tanzania (manuscript in preparation).

Participants’ sampling and recruitment

Key informant interviews (KIIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted among health providers and health leadership from health facilities and the communities in the areas of these study districts. The number of people involved in the KIIs and FGDs was predetermined at 10-15 participants. The selection of participants was conducted in consultation with the health provider in charge of the health facility study sites in each of our research study districts. Health providers involved in ANC, PNC, reproductive health, and family planning were recruited through their willingness to participate in a KII or an FGD. All health providers had been working for more than a year at the facility. Other health providers who were involved in health management and leadership related to reproductive, maternal and child health services within the district, and part of the district health management team, were also approached to participate in the KIIs and FGDs.

To reduce faulty insight and risks of biased sampling, the KII and FGD participants were required to be residents in the local community, of varying levels of socioeconomic status. All participants also had to provide informed consent to participate in the research, including permission to be recorded during the KII and FGD. They were told that all their inputs would be completely confidential and that no identifying information about them would be recorded beyond the information collected in the informed consent process.

The research team developed an interview guide, with an overall research objective focused on individual and community-based factors (barriers or enablers) to women accessing reproductive and maternal health services (including ANC and PNC services).

Data collection

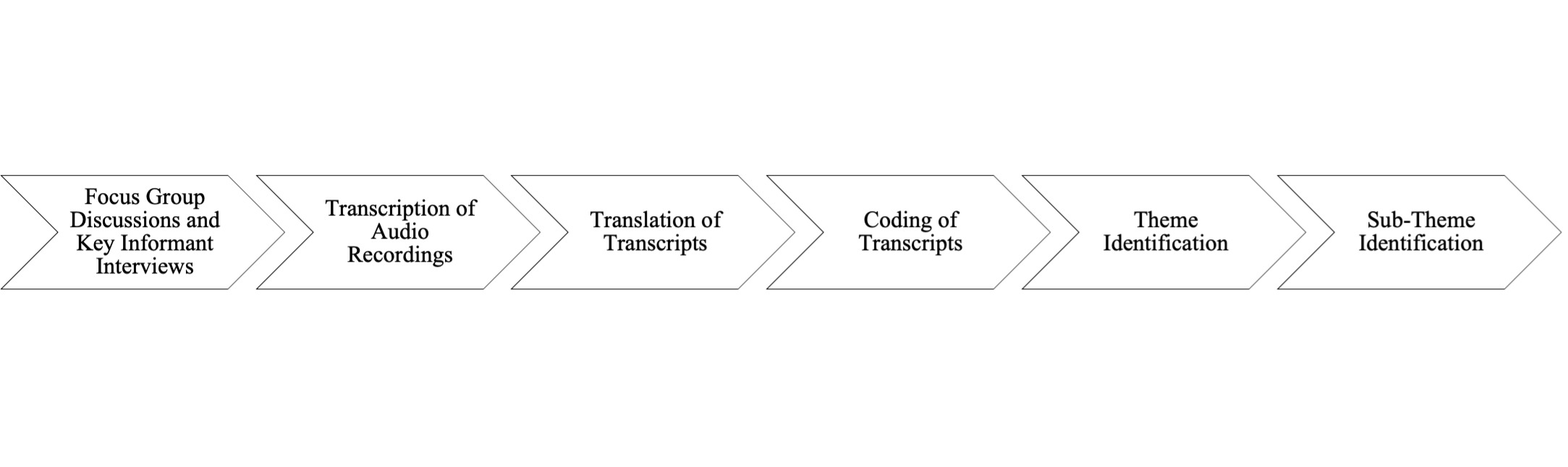

First, an interview guide was developed in English with a set of questions to lead the discussions (Figure 1). Next, it was translated to Kiswahili and then translated back to English (Figure 1). Data collection was done during the months of December 2017 and May 2018. KIIs and FGDs were conducted in a quiet location, and privacy was ensured to enable discussants to feel free and express their opinions. These KIIs and FGDs were conducted separately for females and males. In addition to taking field notes during the KIIs and FGDs, all sessions were audiotaped (Figure 1). On average, the sessions took about one hour.

KIIs and FGDs were chosen over other qualitative methods, as group dynamics and interaction were thought to create better anonymity and spontaneity.5 The combined effect of the group produced a wider range of information, insight, and idea than the individual responses.5

The KIIs and FGDs were conducted by skilled moderators who had training and experience in leading these sessions in similar contexts in rural Tanzania. A female research assistant and another female team member conducted the KIIs and FGDs among the health providers.

Data analysis

Tape recorded data was transcribed in Kiswahili and then transcribed to English (Figure 1). Any outstanding questions, clarifications, and confirmation of findings from the initial transcription and coding phases were discussed among the research team (SC, AL, AE), until consensus was reached (Figure 1). Thematic analysis based on initial coding was used to identify emergent themes and triangulate the information collected, facilitated by NVivo for Mac v11.4.0 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) (Figure 1). This inductive approach allowed for links between research objectives and findings from raw data (Figure 1). It helped develop a deeper understanding of emergent themes’ underlying experiences and processes (Figure 1). Verbatim quotations were frequently used to illustrate the responses of the respondents on important themes and sub-themes (Figure 1).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of Ifakara Health Institute, Queen’s University, and the National Institute for Medical Research in Tanzania Institutional Review Board. Consent at the community and individual levels was obtained in verbal and written formats. Each participant was given a copy of the transcriptions. In addition, the research assistant collected information regarding age, sex, marital and occupational status.

RESULTS

A total of 4 KIIs (1 District Nursing Officer and 3 ANC Nurses) and 2 FGDs were conducted among a group of 13 health providers and allied health professionals in the health facilities (Table 1). Unfortunately, the District Nursing Officer in Geita was unavailable to participate in the KII and FGD when the research team attended the facilities in the district. All health facility interview sites were to become recruitment sites in a cluster-randomized trial evaluating the delivery of a package of interventions, with an intent to improve processes of maternal health care in rural health facilities in Tanzania (manuscript in preparation). The participants identified multiple barriers and enablers to accessing family planning and ANC services, which we classified into two major themes (Figure 2). Several sub-themes also emerged (Figure 2) and have been described with supporting quotations translated below. They have been taken verbatim from the KII and FGD transcripts.

Theme 1: Factors relating to women in the context of their family and community

Lack of autonomy in a patriarchal society

Women in these communities lacked the autonomy to make important, life-impacting decisions regarding their personal health. In many cases, the man of the household had to be consulted prior to any action regarding their well-being. Specifically, although women may have received education at the clinic regarding their health and well-being, decision-making was always in the hands of men (who had very limited understanding regarding their spouse’s health).

“A large percentage of women have neither the right nor the authority to make their own decisions.” (ANC Nurse)

“‘There is one woman who died. Before she died, they gathered information. She started to feel pain at night. It took a while until her husband allowed her to come to the dispensary. The pain continued but her husband told her, “wait for the morning, we will go to the hospital.” When she reached our clinic that morning, she lost a lot of blood and the uterus was ruptured. They get problems because they can’t make decisions until a man decides.’” (District Nursing Officer)

Other nurses offered similar insight:

“But there is one challenge. There are many women who cannot make decisions. She can get sick, or she will get sick, but even if there is money inside, she cannot take it and go to the health service, if the man is not there.” (ANC Nurse)

“As we have said, based on the same challenge we have seen, it means that a large percentage of women have neither the right nor the authority to make their own decisions.” (ANC Nurse)

A social worker described the lack of understanding men have towards their spouses’ reproductive health:

“‘The education that women receive at the clinic is hard to reach for men, and even if a woman tells a man “we have been told so and so,” his understanding is limited, unlike him attending a clinic and receiving education from a health provider.’” (Social Worker)

The use of contraceptives has been declared as “taboo” in Tanzania:

“Many women use contraceptives in secret. She comes by herself. There are very few who come with their husband.” (ANC Nurse)

Lack of knowledge and education regarding healthy pregnancy and pregnancy complications

Lack of knowledge regarding the severity and detrimental effects of disease on pregnancy and pregnancy complications also harmed women’s health in these communities. Therefore, the health concerns were often swept aside, for such conditions have little to no benefit. This may have stemmed from the lack of education members of the community have towards the condition, which contributed to poorer health outcomes as a result.

“In the case of a pregnant woman, she may come alone and test for HIV or other sexually transmitted diseases. She probably needs to get counselling together with her husband. You cannot give her treatment because when she gets home, she will continue having unprotected sex, this is a challenge.” (ANC Nurse)

Lack of financial resources or control over financial resources

The lack of autonomy of women in these communities was provided in many shapes and forms, including as a financial barrier. With the inability to access financial resources in the absence of their partner, women in these communities were unable to seek access to healthcare in a timely manner, thereby contributing to worse health outcomes.

“‘The other is the financial problem, they don’t have their own money. She comes to tell you that “her husband left,” and she has been told to go to the regional hospital for further treatment, but she cannot go because she has no money until her husband returns. Where is the husband going? He went to drink alcohol. They do not own money at home, a man has control over all the income and all the decisions.’” (DNO)

Use of traditional birth attendants

Many of the health issues women face in Tanzania require specialized medical care and immediate attention by physicians at hospitals. However, the reliance on alternative care practices, such as midwives and traditional healers, falls short. Specifically, while they may be able to recognize many of the medical conditions presented, they were unable to attend to them in the same manner that a physician would. This led to a delay of treatment when medical attention was required, placing both the woman and child at an added risk.

“It is not that they are admitted (when you refer them to a higher level of care). You tell her to go to the district hospital now, but due to the lack of money she doesn’t go and goes to a traditional midwife. The midwife who is watching her tells her she will help them. Now that they have anemia at the time of delivery, the blood keeps flowing out. The midwife fails and they have to return to the hospital.” (DNO)

Lack of male involvement

Thus, male involvement is considered one of many factors to improve maternal health. Such negligence had many negative implications on the health and well-being of pregnant women, such as the inability to seek care in a timely manner due to a lack of awareness and concern for maternal health from men.

“The challenges they face, some of the women and their spouses are unwilling to bring them to the clinic.” (ANC Nurse)

In select cases, the lack of male involvement in ANC dictated the inability of women to seek care entirely. Additionally, women were hesitant to visit the clinic without the support of their husbands, resulting in a delay in visiting the clinic until the time of delivery.

“‘There are some who can tell you that, “isn’t there a law to come with your husband?” Others regard the law of coming with a spouse as a precautionary measure of delay in coming to the clinic. For example, she will tell you “My husband was not there so I did not come to the clinic,” so she carries the pregnancy from day one, until she comes to birth without a clinic card.’” (ANC Nurse)

Cultural beliefs as barriers to accessing family planning and ANC services

There are many cultural beliefs and misconceptions that serve as a barrier for women seeking ANC. Many of these beliefs were based on superstitions and rooted in witchcraft or supernatural powers. The act of being ‘bewitched’, for example, was associated with miscarriage. Additionally, the condition of anaemia was misrepresented and resulted in delays in seeking medical attention.

“Superstitious beliefs are that she can be bewitched, the pregnancy may be lost, or the pregnancy may be miscarried.” (ANC Nurse)

“They say, if your wife is pregnant and has anemia, this means that the child is not yours. Her lover goes to the witchdoctor and the blood begins to drop.” (ANC Nurse)

Furthermore, an attempt to hide one’s pregnancy from other members of the community in fear of “evil eyes”, a common superstition, acted as a deterrent for women seeking ANC. It delayed pregnant women from visiting the clinic for several months.

“‘We say “you just got pregnant. When you begin to declare yourself pregnant, that pregnancy may come out. Some have evil eyes, others hear it and they will feel jealous or some are witches.” So when a pregnant woman of one month starts going to the clinic, in our tradition and society, it means they are often publishing their pregnancy, So, many mothers are late, coming five months on.’” (District Nursing Officer)

“‘The problem that causes them to do so is just beliefs, which is a misconception. For example, you can question a woman “why did you come for only one visit and give birth?” She tells me “I can’t show it to the public when the pregnancy is young, people may look at me with evil eyes.” Someone went to a witch doctor and was told she got a miscarriage because she was looked at by someone, while heading to the clinic.’” (ANC Nurse)

An ANC Nurse described another cultural belief:

“They think the Norplant will disappear inside the body or a loop will hurt a man during sex, and a woman will be a prostitute.” (ANC Nurse)

Theme 2: Factors related to health system barriers

Lack of infrastructure, equipment and health provider resources at health facilities

Unfortunately, the barriers to ANC and pregnancy care did not end upon arrival at the clinic. The lack of health facility resources resulted in the need for women to come equipped with the items to aid in their delivery process.

“Other problems exist in the facilities. You find there is not enough equipment. Materials are scarce so it becomes a challenge. You hear that pregnant women are instructed to come with some things so they can deliver themselves there.” (Social Worker)

This scarcity of equipment was a notable health system barrier, as it compromised the delivery process itself, and acted as a source of added stress and worry for women. Furthermore, the inability to complete testing required tests to be done at external laboratories, which lengthened the care process even more.

“The problem that concerns us is that women who come to the clinic have to get all the services in the antenatal clinic. The biggest problem comes with the hemoglobin test. We don’t have a machine and when she has to test urine protein she has to go to the laboratory. That is a challenge.” (ANC Nurse)

Lack of confidentiality and feelings of stigmatization when receiving health services

Women that voiced their concerns regarding health issues or the need to uptake health services, felt stigmatized against, and neglected. When medication was provided for the mother and her child, there were instances where the husband also consumed the same medication, after refusing to get tested himself.

“‘There are a few who are open and tell their husbands that they tested positive and are given medication to use to protect themselves and their babies. When a woman advises her husband to test for HIV the man refuses and says “if you have been tested and have HIV, I am also positive.” You find a man taking the medication his wife was given at the clinic without him being tested.’” (ANC Nurse)

DISCUSSION

This study gives an in-depth insight into a range of barriers and enablers that impact a woman’s decision to seek maternal healthcare from the perspective of health providers in the community. Specifically, this includes barriers resulting from patient-related and health services-related factors that culturally, financially, and systematically impede access to maternal health care (Figure 2). For example, patient-related barriers included the lack of autonomy in a patriarchal society, lack of knowledge and education regarding healthy pregnancy and pregnancy complications, lack of financial resources, use of traditional birth attendants, lack of male involvement, and cultural beliefs (Figure 2). Health system-related barriers included the lack of infrastructure, equipment and health provider resources at health facilities, lack of confidentiality and feelings of stigmatization (Figure 2). Interestingly, reduced stigmatization of HIV+ women was identified as an enabler that increased maternal and reproductive health services uptake in the study districts (Figure 2).

According to the KII and FGD participants, decision-making power involving ANC and household finances are dictated by the male head of household, who is often not involved in their wife’s maternal healthcare. In 2011, a focus group study was conducted with women and men across rural districts in Tanzania.6 Notably, the choice that women made regarding delivery location (hospital, primary care clinic, or at home) was largely influenced by their husbands, who often lacked a complete understanding of the situation.6

Education and general knowledge of healthy pregnancy and complications were also noted as barriers to adequate care for pregnant women, often resulting in delayed access to care, poor nutrition, and/or sexually transmitted diseases.7 A study in Nepal reported the unequal use of maternal care services depending on the mothers’ education level, wealth quintile, knowledge of danger signs, ANC service utilization, and distance to a health facility.7,8 More educational training sessions should be implemented, collaborating with health providers in the community, to address misinformation and promote the uptake of knowledge.

KII and FGD participants revealed their lack of access to financial resources and further explained how this serves as a significant barrier to ANC services. In a study aimed to examine the correlation between the role of health insurance coverage and the uptake of maternal health services, it was determined that women with health insurance had appropriate timing of first ANC attendance, compared to those who lacked insurance.9 Those with financial stability are also more likely to receive skilled birth attendance upon delivery.9

Traditional Birth Attendants serve many critical roles in the field of maternal health. This includes conducting deliveries at home, providing education, arranging transportation, accompanying women in labour to health facilities, providing psychological support, and counselling them throughout their pregnancy journey.10 However, some of their spiritual practices may pose significant threats to pregnant women.11 Several studies indicate the need to train traditional birth attendants with the appropriate skills to escalate health issues related to maternal health and to provide women with the most effective information regarding their reproductive health.11

Historically, male involvement in maternal, newborn and child health in Africa resulted in improved maternal and child health outcomes.12 Despite this, male involvement in ANC is especially low in low-income and middle-income countries such as Tanzania.13 Notably, traditional gender roles continue to impede male involvement in maternal health. In a study conducted in Tanzania, semi-structured interviews were completed with women to gather information regarding their perceptions of male involvement in pregnancy and childbirth.14 Results of the study indicated that men were largely responsible for supporting their partners financially; however, they were absent in terms of ANC and delivery.14 Similarly, although women preferred to be accompanied by their husbands, many factors, including traditional gender roles and fear of HIV testing, continue to serve as barriers.14

Cultural beliefs continue to serve as barriers to Tanzanian women accessing family planning and PNC and ANC services. A qualitative study on CHW knowledge and practice to pre-eclampsia in Nigeria demonstrated that the most consistently stated cause of pre-eclampsia by participants is psychological, with the majority pointing to depressive thoughts (due to marital conflict or financial worries).15,16 Similarly, eclampsia was believed to be due to prolonged exposure to the cold.15,16 In another study conducted in an urban region in Tanzania, where traditional beliefs are held by some, but not most of the population, half of the participants believed that evil spirits and exposure to the fire were causative agents for pre-eclampsia.17

Regarding health system factors, a lack of infrastructure and resources impede a woman’s ability to access ANC comfortably and/or safely. The lack of health facility resources leaves many pregnant women in a difficult situation and reluctant to give birth in a hospital, especially if there is the added risk of complications that cannot be attended to.18 One study conducted in Ethiopia reported that the increased preference for home births is shaped by negative experiences with modern health systems, including the competence of health care providers and the lack of necessary resources, such as drugs and equipment.18

Additionally, both traditional birth attendants and ANC Nurses cited the lack of confidentiality and stigmatization pregnant women face when accessing maternal health services, particularly if those women are HIV+. In some communities, there is still prominent stigmatization of people who are HIV+. If a pregnant woman tests positive, it could exacerbate the feelings of isolation/judgement that she already experiences from her community. A study conducted in Kenya examined the fears related to HIV/AIDS, and how it affects the uptake and provision of labor and delivery services.19 Semi-structured interviews revealed that fears of HIV testing, involuntary disclosure of HIV status to others, and stigma attributed to HIV/AIDS, inhibit many women from delivering in health facilities.19 However, interestingly, in our study, some health providers reported that some HIV+ women experienced reduced stigmatization, which increased their uptake of reproductive services.

Strengths and Limitations

Participants of the KIIs and FGDs were made aware that their inputs were completely confidential and that no identifying information would be recorded. Interview questions were initially open-ended and then redirected at times to understand certain themes, which allowed participants to express their experiences openly and freely. The themes were systematically identified, and all KIIs and FGDs were qualitatively coded by three people using NVivo 12.0 software (Figure 1). Discussions had to reach a consensus on the most important themes and subthemes to include in the paper.

A significant limitation of this study is its qualitative nature. Qualitative studies have an increased risk for error and biased input. Interviewers are also likely to guide answers. Therefore, this process doesn’t ensure maximal accuracy and reliability of our results, providing our study with less internal validity. Another limitation of this study is that we obtained qualitative data from only four districts in Tanzania. Therefore, it is unclear if these results can be generalized to the country, or even to other low-income countries with similar health disparities.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the perspectives health providers have regarding barriers and enablers to reproductive health and ANC services in rural Tanzania. Two major themes that were classified as barriers, include patient and health system related factors. Among patient-related factors, we identified the following subthemes: lack of autonomy in a patriarchal society, lack of knowledge and education regarding healthy pregnancy and pregnancy complications, lack of financial resources, use of traditional birth attendants, lack of male involvement, and cultural beliefs. Among the health system related factors, barriers included: lack of infrastructure, equipment and health provider resources at health facilities, and the lack of confidentiality and feelings of stigmatization. Interestingly, reduced stigmatization of HIV+ women was identified as an enabler. Overall, this study highlights the need to implement more initiatives that will address and overcome barriers related to the uptake of ANC and PNC services in the rural districts of Tanzania. Furthermore, this study also indicates the need to find strategies to improve male involvement and family support in the local context.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants, health providers, and researchers for their contributions to this study. We also thank the program directors and managers at Innovating for Maternal and Child Health in Africa initiative and Canada’s International Development Research Centre, for continuous support and input during the research process. Ethical clearance was obtained from Institutional Review Boards of Ifakara Health Institute, Queen’s University, and the National Institute for Medical Research in Tanzania Institutional Review Board. Consent at the community and individual levels were obtained in both verbal and written formats. Each participant was given a copy of the transcriptions. Information regarding age, sex, marital and occupational status was collected by the research assistant and remained with the data.

Availability of data and materials

Summaries of the data are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Funding

This work was carried out with the aid of a grant from the Innovating for Maternal and Child Health in Africa initiative - a partnership of Global Affairs Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and Canada’s International Development Research Centre.

Authorship contributions

Conceptualization by KY and RPT; Data curation by PDM and RPT; Preparation of Table 1 by KY, NW and MC; Preparation of Figure 1 by SC; Preparation of Figure 2 by MC; Formal analysis by MC, SC, AE, AL, SK, NW and KY; Funding acquisition by KY, RPT and AN; Methodology by KY, RPT, PDM, EE and AN; Project administration by RPT, KY, AN and EE; Supervision by KY, RPT, EE and AN; Writing of original draft by KY, MC, SK, SC, AE and AL; Review and editing by KY, MC, SC, AE, AL, SK, NW, PDM, GS, EE, RPT and AN The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests (includes financial and non-financial). The authors completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ (available upon request from the corresponding author) and declare no conflicts of interest.

Correspondence to:

Melinda Chelva

MSc (Candidate), Queen’s University

56 Boulderbrook Drive

Scarborough, ON

M1X 2C2

[email protected]; 647-746-1491