The spread of COVID-19 in Myanmar was evaluated as an opportunity to fortify the call for peace between ethnic groups across the country and to strengthen the resilience of the health system towards the end of 2020.1 Myanmar responded to the impending COVID-19 breakout with the formation of the Inter-Ministerial Working Committee and of the National Central Committee to prevent, control and treat COVID-19. In particular, the National Central Committee, chaired by State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, aimed at fast-tracking activities at the central level such as case investigation and management, providing community awareness and disseminating updates regarding the pandemic, securing funding, procuring essential medicine and equipment in due time.1 It was probably thanks to these early interventions that, during the first wave, there were only 374 registered cases and six deaths, and the last local transmission was recorded on 16 July, 2020.2 It was difficult to expect such a result would be maintained, considering that the previous half a century of military rule left Myanmar’s healthcare system largely neglected, critically underdeveloped, and catastrophically underfunded.3,4 When the civil government took over the country 10 years ago, they increased both the capacity and the quality of the health care system.5 During the COVID-19 pandemic in Myanmar, community awareness of public health initiatives, sanitation and hygiene practices and disease prevention strategies were supported more efficiently and effectively through state media led by the State Counsellor, State Counsellor’s social media Facebook page, Ministry of Health and Sport’s website and social media Facebook page and person-to-person civil society organization-led communication.6 Many ethnic armed groups in Myanmar seemed willing to put aside differences and work with the central government to help address the pandemic.

Following the military coup of February 1, 2021, the relatively small and fragile, but recently thriving health care system is now under strain. Health-care workers in the country say Myanmar is experiencing a profound health system collapse. The military are reportedly occupying public hospitals across the country, which enables the police to arrest wounded people easily. Direct essential health services provision and capacity-building of the public health sector are severely impaired, thus limiting the availability of life-saving interventions and likely resulting in an increase of preventable cases of morbidity and mortality.7 Regular healthcare services are unlikely to be restored if the military continues to harass and arrest healthcare workers, medical staff, and the deans of medical universities.8

In the meantime, COVID-19 is resurging and quickly spreading all over the country because of inconsistent application of contact tracing and quarantine practices, poor surveillance, overwhelmed health centers and hospitals, shortage of supplies, including oxygen, lack of skilled staff and difficulties in accessing testing facilities.7 Myanmar had begun its COVID-19 vaccination program on 27 January, with healthcare staff and medical workers being the first to receive vaccines produced by the Serum Institute of India, but the immunization campaign has collapsed following the military coup. As of July 2021, about 3% of the population got vaccinated.9 On 3 February 2021 there were 140 600 officially confirmed COVID-19 cases, and on 22 July 246 633.10 However, information coming from social media and from reliable sources describes a much more serious picture with a much higher number of cases and an increasing number of deaths.

Fearing that a return of the military rule of the 20th century would sweep away the improvements recently achieved in the country, doctors and nurses in Myanmar are leading the resistance through a Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM), minimizing work in public hospitals under military control, closing medicine and nursing universities. CDM health personnel used private and charity clinics to provide medical assistance at reduced fees, collaborated with general practitioners, ensured HIV and TB services, and organized staffing ambulances and clinics in the street.11

Representatives of the democratic health and university institutions continue to work to create the conditions for a resumption of the call for peace throughout the country and strengthen the resilience of the health system. The federal National Unity Government (NUG) appointed by the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH) and representing the democratically elected parliamentarians, with its Minister of Health (MOH) has devised an interim health service delivery plan to provide people-centered health care during the revolution against all challenges.12

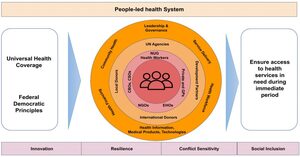

The strategy is developed on two main cornerstones, Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and Federal Democratic Principles, and underscores seven interconnected and pivotal pillars of health systems (Figure 1). Following the Plan, local communities play an essential role to set up a people-led health system and should coordinate efforts with different health actors (Pillar 1), including the MOH, that will provide health policy and strategic directions, ensuring leadership and accountability (Pillar 2). Primary health care services should be prioritized, including trauma, and injuries (Pillar 3), and provided with coordinated efforts by public and private health actors, including general practitioners, NGOs, and ethnic and community organizations (Pillar 4), whilst also strengthening the health information system (Pillar 5). Medical products and supplies, including COVID-19 vaccines, should be secured in coordination with international agencies and development actors (Pillar 6), which are encouraged to repurpose their financial assistance to local health funds or organizations that are providing essential health services (Pillar 7).

A specific plan has been devised to strengthen community-based COVID-19 management, including protocols for disease prevention and treatment.13,14

The implementation of the strategy will uphold the use of innovation, resilience and conflict-free, equity and social inclusion.12 As such, this strategy can be potentially evaluated as an opportunity to fortify the call for peace and restoration of democracy and human rights, showing that the health sector of a country can be reshaped and revitalized in times of great adversity. The NUG Ministry of Health fosters the “health as a bridge for peace (HBP)” multidimensional policy, which supports health workers in delivering health services and programs in conflict and post-conflict scenarios, whilst contributing to peace-building. The framework is defined as an integration of peace-building concepts and strategies into health relief and health sector development, and underscores health as a neutral meeting point to bring conflicting parties to discuss mutually beneficial interventions.15 Health is a universal human right, it is neutral, it cannot side with any party. Thus, the international scientific community should support the Plan and the efforts of the Myanmar democratic MOH, as a means of restoring peace and democracy in the country.

Unfortunately, what is happening in Myanmar is continuously repeated in many parts of the world. Conflicts trample the right to health both locally and globally. As a matter of fact, the COVID-19 pandemic has shown us how health is a global good. The international scientific community, with the help of relevant stakeholders, should demand to monitor the progress of health determinants in conflict areas in order to promote interventions aimed at restoring this fundamental right.

Funding

None

Authorship contributions

All persons listed as authors have contributed to preparing, writing and editing the manuscript.

Competing interest

The author completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ (available upon request from the corresponding author) and declare no conflicts of interest.