Cesarean section (c-section) is the most common major surgical procedure conducted in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).1,2 C-section poses inherent risks to patients, many of which occur at higher rates in LMICs. For all surgical procedures conducted, the most common post-operative complication is surgical site infection (SSI), with incidence estimated as high as 30.9% in some low-resource settings,3–12 where high SSI rates have been associated with factors including lack of effective pre-operative antibiotic use,13 lack of antiseptic skin prep,14 antibiotic resistance,15 and lack of sterilization policies.16 Interventions have been designed to attempt to address high SSI rates, but strategies for optimal care of patients at risk of developing an SSI after c-section would be strengthened by understanding the general care-seeking behaviors and decisions along the pathway of peri-partum care for delivering mothers, including their identification, intervention, and follow-up.

Elsewhere, mapping care pathways has provided opportunities for quality and safety improvement for specific disease areas but has only limitedly been applied in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA),17–19 and even less often, to surgery patients in SSA. The few studies on surgery care pathways have explored barriers that patients may face in accessing surgical care20 and community perceptions and misconceptions of surgical care, which were in turn used to improve programs and access to services.21 However, to our knowledge, there are no studies on post-operative care pathways, and in particular none currently on post-c-section in SSA. In this study among women who delivered via c-section in rural Rwanda, we aimed to elucidate the personal experiences of healthcare seeking, delivery, and post-discharge follow-up.

METHODS

Population and study setting

The study was conducted in the rural district of Kirehe in the Eastern Province of Rwanda, 120km by car from the capital city, Kigali. In Rwanda, ninety-seven percent of deliveries take place at health facilities,22 compared to 91% from 2011-15 and 69% in 2010.23 In 2014, a reported 14.3% of deliveries in health facilities were c-sections,23 and c-section is the most commonly performed operation in district hospitals.24 Kirehe District has 612 villages occupied predominately by farming families and a large refugee camp housing more than 50,000 Burundian refugees,25 for a total population of approximately 365,000. Kirehe District healthcare services are provided by the Rwandan Ministry of Health with support from the nonprofit organization Partners In Health (PIH) since 2005. The hierarchical health referral system for the district is headed by a 235-bed district hospital (Kirehe District Hospital; KDH), where patients are referred from the sixteen health centers in the district.

Data collection and analysis

This qualitative study was nested within a larger mobile Health (mHealth) study exploring the utilization of community health workers (CHWs) to provide SSI monitoring for patients post-c-section.26 This qualitative study was designed to capture the nuances and complexities in the experience of women utilizing the healthcare system who received no additional mHealth study-specific follow-up beyond standard of care.

Twenty-five women post-c-section participated in protocol-guided, in-depth interviews. Author BP designed the guides which were revised by TN, LD, and MK during a review period when the team conducted practice interviews with women from the community and optimized the protocol for culturally appropriate content. The interviews focused on the participant’s interactions with the healthcare system during and after her c-section delivery (Table 1). Participant demographics and healthcare outcomes were extracted from data collected during enrollment in the mHealth study at KDH.26 Participants eligible to be interviewed were women randomized between February – March 2018 into the no-intervention (standard of care) arm of the mHealth study. All women enrolled in the study received standard discharge instructions as part of the study procedures. Each woman interviewed was screened over the phone for their agreement to participate, between post-operative day (POD) 21-23. Interviews were subsequently conducted in Kinyarwanda in-person at the participant’s home by POD 30, by one of two trained Kinyarwanda-speaking data collectors, LD and MK.

The interviews were translated and transcribed verbatim from Kinyarwanda to English. One author (BP) used a subset of ten randomly selected transcripts to identify deductive and inductive codes to develop a coding manual. Four codes were added de novo during the coding phase and prior transcripts were re-coded. Data analysis and theme extraction were guided by the Grounded Theory approach with cyclical analysis as described by Hennink et al.27 Thematic saturation was achieved, which is the point in qualitative data collection when no new issues are being raised by subsequent participant interviews. The entire dataset was coded based on thematic content analysis27 by the primary analyst (BP) using Nvivo 12 (QSR International, Doncaster, Australia).28

Ethical approval

We received approval for this study from the Rwanda National Ethics Committee (Kigali, Rwanda, No.848/RNEC/2016) and the National Health Research Committee (Kigali, Rwanda, NHRC/2017/PROT/004) and from Partners Human Research Committee (Boston, USA, 2016P001943/MGH). All participants were first provided a written consent for the larger mHealth study, then a consent form in Kinyarwanda that explained their voluntary participation in the interview portion. This was read to them in Kinyarwanda and their consent was obtained by participant signature before study enrollment. All interviewed participants received 3000 Rwandan francs (RWF) (US$3.30) for their time. This amount was determined by local colleagues to be fair compensation based on daily wage for unskilled labor, and was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Rwanda National Ethics Committee (RNEC).

RESULTS

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants

The women interviewed for the study were aged 19 - 42 years, largely married or living with their partner, primary-school educated, and living in subsistence farming households. 72% rely on a monthly household income level ≤ 10,000 RWF (US$11.63) (Table 2). Public transport and moto were the major means of transport to a health center (81%). The leading indication for c-section was previous c-section (n=8, 32%) (Table 3). The breakdown of indications is consistent with previously published distribution of c-section indications in this setting.29

Healthcare pathways

It was my wish to deliver my baby at [my health center] but it was God’s plan to deliver my baby at KDH (Transcript 6).

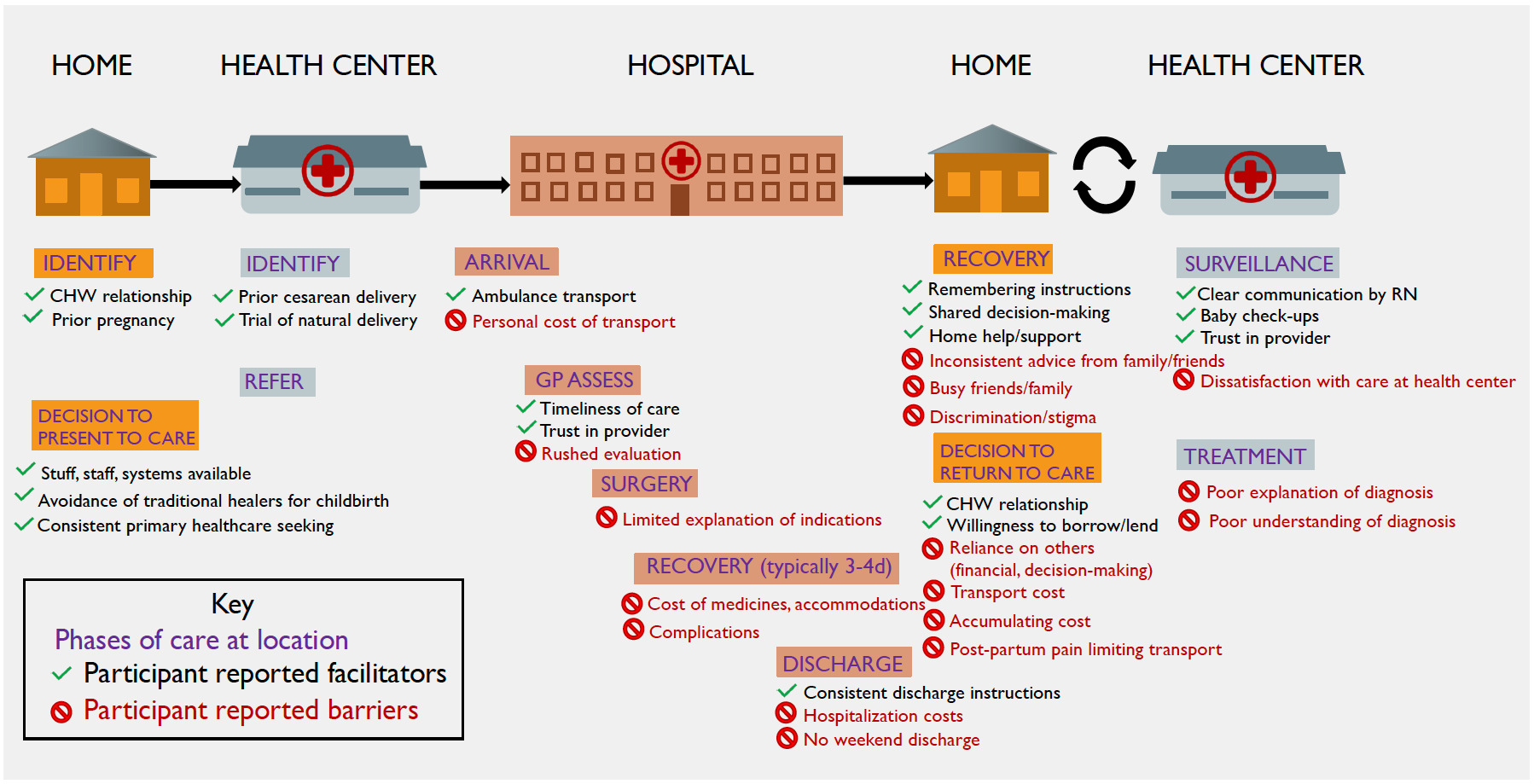

Based on thematic analysis of the interviews, we conceptualized a process map for healthcare-seeking surrounding c-section, including common facilitators and detractors at phases of the healthcare pathway (Figure 1). There is a common progression through the healthcare system – from health center to referral to KDH, to surgery and discharge, to wound care follow-up, and finally to recovery. Shared events, decisions, and deviations from this pathway are denoted on the process map and will be explained in the results below, supported by illustrative quotations.

Delivery location and method

Most women went to their health center before being referred to KDH for c-section which follows the design of the tiered referral health system in Rwanda. They described experiences like, “Actually, before I went to KDH, I first had to go to the local health center. They tried to help me deliver my baby, but it didn’t work, and I was getting very tired and the baby was too. Then after all the trials, they decided to transfer me to KDH” (Transcript 13).

A few women presented as direct admissions to KDH. Stated reasons for direct admission were either consistent primary care-seeking at KDH, or prior experience with c-section: “I thought to go there [KDH] because I believed that doctors from KDH provide a better service to the patients than anywhere else. That is why I didn’t go to the health center” (Transcript 19).

The birth experience was often informed by prior pregnancies. Women who had previously given birth by c-section were commonly referred directly to KDH or, infrequently, allowed a trial of natural delivery at the health center prior to being referred. “You see, this was the third time I had a c-section, so when I got to [my health center], the nurse tried to help me deliver my baby in a normal way, but it didn’t work. I told her that I can’t give birth without having surgery. So, they transferred me to KDH” (Transcript 14). Despite having had c-sections before, many women still went to the health center hoping they would deliver their child naturally. “My wish was [to deliver] my baby in the normal way because I got surgery on the firstborn” (Transcript 20).

Hospital care

When we inquired about the patient’s understanding of why she had a c-section, answers were limited. Often, women in our study reported that the indication for c-section was their previous c-section. Another common response was, “some complications in the belly” (Transcript 10), which when probed was not expanded upon.

Most women were hospitalized for 3-4 days following their c-section. According to the main study outcomes data, five women experienced an extended stay at KDH, which was defined as greater than four days. One woman reported that she was told to stay near the hospital for three weeks due to a wound infection. A woman who was pregnant with twins described being asked to stay at KDH instead of going home before her delivery because she didn’t have money to pay for guaranteed transport to come back. She stayed in Kirehe for six days before she delivered twin girls. She was admitted for a total of nine days. One woman said, “Because I was bleeding, I spent one week there” (Transcript 25). In explaining her extended 5-day stay another woman stated, “they just told us they don’t let patients go back home on the weekends” (Transcript 4).

We asked explicitly if hospital staff offered any discharge instructions about their wound, and if they could remember what they were told. All women in the study were given the same printed discharge instructions that were provided as part of the mHealth study enrollment, including instructions to keep the wound covered until their follow-up appointment at the health center and warning signs to return to the health center. Consistently, women were able to recall instructions, like “[She] told me that I have to keep my wound away from urine, breastmilk, and unclean water because if I don’t, my wound will get infected and it will be hard to recover. They told me that I have to put on clean clothes to keep it safe” (Transcript 11). And many women could also recite signs and symptoms they were warned to look for in their wound, including, “If I feel pain from it and if I see that the wound is getting swollen or a very bad odor comes from it then the wound is in danger” (Transcript 10). Pus discharging from the wound was the most commonly cited warning symptom recalled by study participants.

Despite receiving written discharge instructions, one woman remembered her discharge differently:

They didn’t tell me anything, because you know when they’re about to discharge a patient, the doctor comes to check on that person, he checks on the wound to see how it’s doing, he presses on the belly to make sure there is not any problem inside, and then once he sees there is not any other problem, they just sign for your discharge and you go back home and keep going to the health center for your wound dressing (Transcript 1).

Post-discharge care

On discharge, women were told to return to their closest health center for a wound check appointment in three days. A majority of the women describe returning to care for wound checks, wound cleaning, or dressing changes. Instructions to continue returning for dressing change came from the health center when she visited. One woman who was discovered to have a wound infection at her health center follow-up explained:

When nurses were removing [the sutures], they realized that my wound had pus and they told me to come back on the following day. So, I had to go to the health center every day to treat that problem of pus and to get my wound cleaned. So, the nurse really followed-up on my wound until my wound was fully healed (Transcript 24).

Many women said they experienced no complications during their recovery. For example, "Actually, after I got surgery, I didn’t have any complications and my wound quickly recovered and I now have the normal life I used to have before I got surgery (Transcript 3).

Post-operatively, mothers judiciously returned for their baby’s follow up appointments. No women relayed any barriers related to returning to care for her baby. The common reasons for returning to care with the baby were routine vaccinations or “flu.”

Support and decision-making in the pathway to care

Setting and provider decisions

When asked what their first stop is if a health concern arises, responses varied. A few women said their local Community Health Worker (CHW) was their first stop:

Actually, when I got malaria, I first went to see the Community Health Worker and she helped me to get to the hospital. We went there together, and they gave me pills. She really cares about me. […] Because she is the only one who cares about my life most of the time, she even cared for me when I had a [traumatic accident]. She is like my mother in fact, since my mother lives far away from here (Transcript 21).

Many women said the health center is the first place they would go because there are medications available, trained staff, and referrals to KDH from the health center if indicated. “The mindset of the people here in the village in general and myself, we have this mindset that whenever I have a problem I have to rush to the health center” (Transcript 1).

And many women said KDH is the first place they would go. For some this was out of convenience. For most, it was because they associate KDH with the best care and the least delays, or because they saw shortcomings in the health centers or CHWs, “[I go to the hospital first] because I believe in them” (Transcript 24).

In considering the available healthcare providers, five women discussed alternative providers, either to explain their use or disuse of these providers. In this study, “alternative providers” was described as anyone working outside of the government hospital system. They are sometimes referred to as “traditional healers” in Rwanda. Three women explained that they felt they would be better served at the health center than with a “religious healer”, as one mother explains:

I don’t want to go see those other people because you see this is my third c-section, do you think I could go see a religious healer and that he can pray for me and the problem could be over? You can understand yourself that I cannot go see a religious healer, I would rather go to the health center and when they find that my case is too difficult to treat, they transfer me to Kirehe Hospital (Transcript 1).

Another explains, “No, I can’t. Since I have health insurance I can’t go to fake doctors. […] I am Adventist, I only believe in God” (Transcript 6).

One woman described getting, “herbs from the forest” from her mother-in-law which she then ate during her recovery, seeking them, “because I was in so much pain.” When asked why she took them, she said, “In fact, she told me that she once gave that herb to someone else who had the same problem and it worked, that is why I thought I could use it too. […] You know, when someone is in as much pain as I was, she can take or do anything to end that pain” (Transcript 14). Other than these examples, the women interviewed denied seeking care from alternate providers.

Medical care explanation and comprehension

In a previous section, we discussed ambiguity for mothers around the indications for their c-section. Another common topic of ambiguity was the reason for having an issue with the surgical wound. Eight of twenty-five women interviewed were told to continue coming to the health center for wound monitoring. It was infrequent for a mother to provide a meaningful explanation for why their wound became infected, or even what they were being treated for. In many cases they returned to the clinic for wound dressing changes and possibly some medications as long as they were told to, relying on the healthcare provider for further instructions, but not explanations.

I: You say that you have been going to the health center several times for your wound dressing. Were you given any information about that problem, or the issue you were having?

P: No, I didn’t get any explanation of it.

I: So, you were going there, they did the dressing, and you came back home?

P: Yeah, I was going there, the nurse came to see how the wound was doing, applied some medication, and prescribed other tablets for me to take and that’s all.

I: So, they were not telling you anything about that problem, they didn’t tell you what the problem was exactly?

P: No, they didn’t tell me why it would take that long for the wound to get healed.

[…] Maybe. I’m not really sure because I don’t really know what happened to me this time during my pregnancy. […] Yeah, since it’s their expertise, you don’t really have any idea what they are doing. For them they know (Transcript 1).

Women who returned to the clinic post-operatively because of a medical complaint were frequently only able to say that they were given medicine but could not name the medication or what was being treated. Most commonly, inconsistencies were related to specific instructions during the recovery-period (Table 4). Wound-specific misunderstanding included wound complications and concerns about sutures left behind after surgery, such as, “Yes, they told me to keep the wound away from any liquids such as water, urine or breastmilk because it can cause the wound to get cancer, which will cause me serious problems” (Transcript 9).

There were a few women who felt comfortable with the information provided to them, and that they had been fully informed:

I: Did you get an explanation for your illness or a diagnosis from the health center?

P: Yes, they told me that I didn’t have to be worry about my wound, it will get better slowly. They told me that they would care for it until it was fully healed and remove the surgery stitches. They really explained to me everything I needed to know (Transcript 18).

Sources of support and information

Women cited many sources of advice, information, and support. For some women this resulted in frustration over inconsistent information or more difficult decisions. Husbands alone were mentioned by six of the women as the main source of help with decision-making about their healthcare. One woman delayed returning to care until she discussed with her husband and he helped her reach care:

In fact, when I first saw those internal surgery stitches, I was not with my husband. So, I had to wait for him to check for me what color those internal surgery stitches were because I couldn’t tell by myself. He told me they that they are blue, and he told me also that I have to go to the hospital because it might be dangerous to stay home without medical care. He had to look for money and the following day we went to the health center. I only delayed by one day and then I went to the health center (Transcript 5).

Some women cited nurses and a few women cited CHWs as main sources of advice and instruction in decision-making for healthcare seeking during their delivery. Two of the women had personal relationships with a CHW:

There is a CHW who was my classmate, so, when I had a problem on my breast, I went to see her and ask her what I could do. I didn’t want to take any medications without asking someone who knows about them. Actually, whenever I have a problem related to my health, I go talk to her because she likes to give me advice (Transcript 13).

Doctors were mentioned as sources of support by a few women. Lastly, other family members living in the home (grandmother, mother-in-law) and friends were mentioned infrequently.

When asked about emotional and physical support during the hospitalization and post-operatively, women more commonly cited their family, extended relatives, and neighbors who would provide help including bringing food and water to the hospital. Some women referenced a lack of support, the main reason being a husband/father of the baby who was traveling, absent, or jailed. Others felt friends and family were too busy with their own lives to lend help to them. “People really helped me when I was still at the hospital, they could bring me food but at home, everyone is super busy with his/her own duties” (Transcript 15).

Financial factors

We asked questions to clarify who had out-of-pocket costs for care and whose decision-making was actually affected by financing their healthcare. Financial issues that were brought up included debts/borrowing money (majority of women), transportation costs (majority of women), hospital costs (many women), health insurance (infrequently), and selling owned property (infrequently). In some cases, families sell what they can to pay for the healthcare costs or borrow money from friends and family and then have ongoing debts to settle.

Yeah, I can say my health care has caused us to live in poverty at home because everything that he has planted/cultivated he has sold them so that we can pay the hospital and live. […] Regarding the livelihood, I’ve told you it’s a problem because we’ve used almost all of the money that we had. And the field crops that were supposed to help us survive we’ve sold all of them in order to be able to pay for the hospital. So, you can understand for yourself how much life is not easy at the moment. That’s the only problem we have, otherwise we are fine, we don’t have any other problem (Transcript 1).

Another woman notes, “Of course yes, you see, I had a chance because I was still depending on my mother’s medical insurance but if I was not, I would have had more problems and I could even [have had to] sell my house to find money for medical care.” (Transcript 12)

Medications were a consistent cost-burden. Women described a system where patients are told they need certain medications and then their family must buy/pay for them before they can be administered. In some cases, this led to delays in receiving medication, and in other cases women felt the medications would go to waste.

I don’t really have any problem but again I want to give advice. Doctors should tell patients medications they have to buy when patients are still at the hospital. Patients should pay for medications that are equal to the days he/she will spend at the hospital. If not, it will be a loss to the patients if they buy much more medication than days, she will spend there. For example, I bought medications and I didn’t finish them because I was sent home the following day (Transcript 23).

Family members and neighbors were most often involved in loans to families for healthcare costs, “My mother had to take on risk and had debts also, just to help me out” (Transcript 9). One woman described receipt of charity funds from her neighbors and friends, “People helped me out, some visitors came with money and they gave it to me and people from far away used Mobile Money to send me some money. I really got helped” (Transcript 10).

Some women claimed that finances directly affected their decision-making. Predominantly, financial constraints were cited as delaying a desired appointment or follow-up by one day to multiple days. This seemed to stem from a lack of disposable income available for transport to an appointment, especially for women who were already in debt from their initial hospitalization. “You mean something they should have done for me to get the treatment quickly and easily? For me, if I could have money at that time, I would have gone to the health center at the right time. There was nothing else to be done, I just had to wait until I had the means” (Transcript 1). And:

Yes, I once missed an appointment because I didn’t have money for transport, and I had to take a debt of 300 RWF (US$0.34) to get to the hospital. I needed my wound to get a new cover on it. […I missed] 3 days, without cleaning my wound, I could feel much pain from it because of the surgery stitches but, at the end of the day, the doctor gave me a new cover on my wound and removed the last stitches (Transcript 25).

Many women described costs associated with their healthcare but said it was not too much to bear. “You see, some money was spent on medical care, but my husband and I tried to manage it. Of course, we had to take some debts, but it was not so much, we really managed it. We have to figure out how we can find other money, it is just life” (Transcript 21). A few women specifically mentioned saving money in preparation for their pregnancy, as a sort of savings fund. “It wasn’t [a lot of money] when we compare to the service they provided me. I remember I paid 8500 RWF (US$9.60) and it was really not that much. You know, when you are pregnant you have to save some money just in case” (Transcript 13). For one woman this involved paying into a communal collection to ensure she would have cost coverage in an emergency:

Yes, there is association called Ingobyi, they helped me out. Actually, we contribute 200 RWF (US$0.23) each month to that association and [from] that [collection] that they take money when a member has a problem to solve, as I did. So, they gave my husband money for transport and we paid a moto driver who helped me to reach the hospital (Transcript 18).

Transportation-related factors

Transport cost is a very common issue both pre-delivery and post-operatively. Many women did not anticipate the additional costs of leaving the health center to get to KDH to deliver, and in some cases multiple follow-up trips to their health center for wound checks after. They mentioned trade-offs they faced to use their money for transport to the hospital, and debts that would accumulate with more trips. “[The financial burden] like feeding my babies, it was very hard to feed them when I was using all the money in transport. I also had debts of 5000 RWF (US$5.65) and I have not yet paid them” (Transcript 25). In another case, a woman explained, “I said that I am going to stay at home and hopefully this wound is going to heal by itself, just because I could not afford transport to the hospital” (Transcript 4).

Lastly, transportation issues unrelated to cost were discussed. Some women cited difficulty with walking/tiredness, some described pain during motorbike rides or “moto shakes,” and infrequently cited were difficulty with availability of transport when needed, and that transportation on the moto was dangerous when the road was slippery and muddy.

Perceptions of illness and care on the healthcare pathway

Perceived infection

We asked patients about their wound infection (8 of 25 women interviewed) and why they think the wound became infected. A few of these women with wound problems thought medication delay or early termination of medication was the cause of their infection. Other causes espoused less frequently included problems caused by the sutures, provider error, her own delay to return to clinic, riding on a motorbike, returning to activities too quickly, and “just my nature” to recover slowly. One woman thought the symptoms of infection were a normal part of recovery, saying, “Actually nothing special happened, I think it is normal to have pus when you have a wound. It was not very serious, just a little pus and it is over now, I am fine” (Transcript 24).

Perceived delays

We asked participants if they experienced delays in their healthcare and characterized their responses – a large majority of participants said they did not experience delays during their delivery or recovery; few women experienced personal delays; and some women experienced health system delays. The health system delays referred to ambulance delays, discharge delay, health center staff delay, and overcrowding at the health center.

Perceived provider trust

Many patients expressed trust in their physicians, and their most commonly cited reasons were that they believed in them, because of their schooling/training, and because they demonstrated expertise. One woman said the physician had strong communication skills with her. One woman expressed trust in her CHW because of her shared experience, having given birth by c-section herself. “We have to [trust them] because they have gotten a degree for curing patients. God gave them knowledge, so we have to have confidence and trust in them” (Transcript 6).

Satisfaction

When asked if she felt satisfied with the care she received, the most common phrases expressed were ‘they gave me everything that I needed’ (majority of women); “really cared about me” (many women), and satisfaction with timeliness of care (some women).

We get a sense for the appreciation of care from women in their descriptions of the care they received:

I spent almost one week and a half at KDH but within all of those days they really cared about me. They gave me pills, they injected me with some medications, they even gave me food. I didn’t have any problems there. […] They really gave me anything I needed, they cleaned my wound, they gave me a new cover on my wound, they gave me medications, actually they did what they were supposed to do (Transcript 22).

Most of the comments concerned the hospital. Some women also expressed satisfaction with their care at the health center level. Women were relieved to receive care when they needed it most, “They gave me everything I needed as a patient who got surgery. One more thing they helped with was that they gave painkillers when my wound was hurting, and I didn’t have money to pay yet. So, when I got money, I paid them back. I was very happy about that” (Transcript 9).

Dissatisfaction

Some women expressed dissatisfaction with the care they received. Factors contributing to this dissatisfaction varied widely. Not receiving medication at either KDH or the health center was again raised. A few women had wound care concerns, either that it was not being checked, not checked carefully enough, or that it remained uncovered when it should not have. One woman expressed concern for how her wound was being managed by a physician at KDH:

I didn’t really appreciate it because they no longer take care of the patient, because you see before […] the doctor who was supposed to remove the bandage and do the wound dressing, he could do it while talking to you gently. They were putting on gloves and removing the bandage very slowly, very gently, and would help you. But nowadays the doctor will come with a scissor and remove the bandage very quickly without paying attention. For me, I don’t really imagine what is happening with doctors nowadays (Transcript 1).

Some infrequent reasons for dissatisfaction were related to ambulance delay, pain, rushed care at the health center, busy providers at KDH, and wasting money on medications. One woman offered that interns should not be providing care to maternity patients.

We asked patients if they had any suggestions to make their path to care easier. One new idea was to provide shelter for a patient’s caretaker at the hospital. There was another woman who shared her concern for the lack of uniformity in messaging that patients receive:

I just want to give my advice. It would be better if you guys provide some trainings to all nurses so that they can give the same information to patients. I am saying this because sometimes I hear people having different information on how safe to keep the wound and this is not good. Otherwise, you are doing a great job. Thank you (Transcript 20).

A majority of women commented on stigma or discrimination in the setting of having had a c-section, either to confirm experiencing perceived discrimination or to comment to the contrary. One woman remarked, “Not at all, contrary to that, people keep helping me in different activities especially my neighbors. Even at home everything is fine, I don’t see any discrimination because of my scar” (Transcript 10), and, another reported, “No, they said that it was God’s plan. […] They came to visit me without any problem. And my husband also accepted what God planned” (Transcript 6).

Some women said they experienced stigma or discrimination after their c-section. A few of them said that people told them they got a c-section because, “people say that we are like men, we were not born to give birth” (Transcript 25). Others related being seen as “disabled” or blamed for needing a c-section because she waited too long to get pregnant again after her first child. One woman, who was pregnant due to rape, described a feeling of isolation after the birth of her child:

Actually, people from my baby’s father keep saying that the child isn’t from their family, but people say that they have to accept the baby because the baby’s father raped me when I was still at school and I found this like discrimination. Only my father-in-law tries to help me but not so much. […] Of course, yes, sometimes my father-in-law says that I can’t do anything because I got surgery. They don’t care about me, and they even don’t care about my baby (Transcript 12).

Only one of these women said that the discrimination or stigma was experienced as a barrier to care, describing that it was related to money. She said, “The only problem occurs when I need money for transport because no one cares about me” (Transcript 12).

DISCUSSION

The existing literature around help-seeking and pathways to care in LMICs often concludes that care pathways are inherently complex with many options, decision points, inflections, and routes.17,30 Our findings, however, suggest that there is consistency in the pathway through care for women undergoing c-section in one rural district in Kirehe, Rwanda, a district with a relatively homogenous population in terms of income and education. A functionally shared pathway emerges for most women during their childbirth and postpartum care. This homogeneity allowed us to construct a process map and then to focus attention on the facilitators and obstacles that enable or disable women on this common pathway. It is important to recognize that this study found that women were largely moving through the health system as it was designed, and therefore interventions should be designed to promote facilitators, to reduce barriers, and to identify and target the women being diverted from this path.

The most common deviations were also shared. Women who struggled to pay for transportation or to seek loans from family or friends were delayed in their care-seeking after c-section. Interestingly, women often were not able to relay the reason for their c-section or relayed conflicting information from healthcare providers. Some of the more startling claims were the misperceptions around post-operative care that may be perpetuated from one mother to another (Table 4). It is impossible to tell whether these misperceptions originate principally from the healthcare providers or the mothers themselves but ensuring the accuracy of the messaging that delivery centers disseminate to expecting and postpartum mothers is imperative to consistent high-quality care.

This qualitative study was not designed to draw conclusions about post-operative complications or to understand the root causes of SSI after surgery in this population. Rather, the qualitative nature of the data reveals patient perceptions and where resources may strategically be deployed to best serve the most patients. From our results, the most frequent and actionable barriers for our study population are transportation costs to access the hospital and return for follow-up visits, and the variety and quality of information that women receive about their health condition.

Beginning with cost, prior research into the cost of c-section in Rwanda suggest that copay alone can be a catastrophic expense to mothers and families.31 Despite the social support of Rwanda’s community-based health insurance scheme, the problem of non-healthcare costs persists and was reiterated by the mothers in our study. Transportation cost specifically has been identified as a predictor of post-discharge SSI.14 One suggested solution to give stipends to decrease catastrophic expenditures32 and to increase demand-side financing for maternal health has been examined in the past, and systematic review indicates that stipends can improve utilization of priority maternity services.33 One alternative solution would be train CHWs to do wound dressing changes in the homes of women to avoid follow-up trips to the health center altogether. This is a potentially cost-neutral alternative in regions with robust CHW networks and would offload the time and transportation cost burden from new mothers. Further benefit is avoiding the physical challenge of motorbike travel to an appointment within weeks of major abdominal surgery. An earlier phase of this study demonstrated that CHWs can be trained to detect and refer SSIs in post-c-section patients.26 In communities where CHW networks are already functioning, upskilling CHWs to provide home-based wound checks would be comparable to other more complex skills being trialed for CHW deployment including palliative care,34 cancer screening,35 and cardiovascular disease risk screening.36

With regards to the under-informed responses and misinformation voiced by post-c-section patients, informed consent and knowledge of their medical condition are two points our team identified for potential intervention. The variety of caregivers and decision-making counterparts that were discussed in this study suggests that there is a need to target educational campaigns which cover common indications for c-section and common complications to all caregivers – mothers, grandmothers, older children, sisters and brothers, husbands. This could help create a network of support for informed healthcare decision-making and dispel lingering stigma and misinformation around c-section.

Lastly, there is some onus on physicians and healthcare workers themselves to provide unified information and to gain informed consent and we suggest implementing additional physician training on discussing health status and health conditions with women, aiming for open communication with patients and delivering patient-centered care. Recognizing the unique challenges of informed consent in LMICs,37,38 this is one of the fundamental non-technical skills of healthcare providers. Our study supports the idea that patients inherently trust their providers because of their expertise, training, and experience, which is something to leverage and optimize.

Ultimately, providing better preparation for women likely to need c-section, to mitigate some of the last-minute burden of information sharing and consent in emergent situations is fundamental to improving the pathway to care. The discussion is further complicated because of the current lack of access to some of the non-operative delivery mechanisms like vaginal birth after c-section (VBAC), which ideally would be available and would reduce the need for c-section for some patients. Until these services become part of the standard of care, our findings may inform other similarly structured rural health systems to improve the care of their operative deliveries at district hospitals around the world, and to intervene where the patients themselves are reporting barriers.

Limitations

This was a single-center study in a district of Rwanda that has been supported by the nongovernmental organization PIH for over a decade. Nonetheless, the health system and the patient population there is very similar in composition to other rural districts in Rwanda, and comparable to other rural communities in the region that have CHW-based hierarchical healthcare systems that serve subsistence farming populations. None of the participants interviewed for this study experienced loss of child or stillbirth, so those post-operative experiences are not represented in our results. Interviews were conducted in Kinyarwanda, and we cannot discount any data distortion due to limitations posed by translation. Despite these limitations, we believe that the qualitative perspective expands our general understanding of the rural mother’s experience with regards to c-section delivery and the post-operative challenges.

CONCLUSIONS

Women who deliver by c-section in Kirehe district largely follow a common pathway through the healthcare system. Listening to the stories and perspectives of postpartum women in their own words, followed by thorough analysis and synthesis of these lived experiences can help us identify deviations from this pathway and areas for quality and safety improvements. Moving post-operative wound assessments from the health center into the homes of patients, and ensuring unifying messaging around c-section indications, care, and complications at the community-level are two of the areas we have identified that may facilitate and optimize this common pathway for all women who deliver by c-section.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Kirehe District healthcare staff who tirelessly care for patients, the Inshuti Mu Buzima Kirehe District office, and the mHealth study participants, without whom this research would not be possible. We also thank members of the mHealth study team for research assistance; in addition to the named study authors, other team members who contributed to data collection and/or study administration were as follows: Jonathan Nkurunziza, Laban Bikorimana, Holly Irasubiza, Naomi Tuyishime, Annonciata Murekatete, Ruth Bagwaneza, and Monique Mukabarinabo. No endorsement of manuscript contents or conclusions should be inferred from these acknowledgements.

FUNDING

The mHealth study was funded by U.S National Institutes of Health 1R21EB022369. Dr. Powell acknowledges financial support from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation International Clinical Research Fellows Program at Harvard Medical School, and the Stanford Medical Scholars Research Program.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTIONS

BLP: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing - original draft

TN: Project administration, resources, review and editing

FK: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, review and editing

LD: Resources, review and editing

MK: Resources, review and editing

RK: supervision, Review and editing

BLH: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, review and editing

RR: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, review and editing

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available upon request from the corresponding author), and declare no conflicts of interest.

Correspondence to:

Brittany L Powell, MD

75 Francis Street, ATTN: Surgery Education Office, Boston, MA 02115

[email protected]