Despite 50 years progress in family planning programming, unmet need for contraceptive services in some regions remains unacceptably high.1 The proportion of sexually active women with demand satisfied for modern contraceptive methods in sub-Saharan Africa ranges from 88% in Zimbabwe to 18% in Chad, and demand satisfied is lowest in the West and Central Africa regions.2 To address these gaps in coverage, there is a renewed global focus on improving quality services to meet the contraceptive needs of women in low-and-middle income countries (LMICs).3 Program implementers require accurate, inexpensive, and timely measures of both readiness (i.e., contraceptive stocks and supervision) and process quality of care (i.e. counseling completeness) to evaluate and inform program improvement.

Currently there is no standard set of tools or methods measuring process quality of contraceptive care for in LMICs.4 Historically, it has been measured through observation of client-provider interactions (“direct observation”), client exit interviews, simulated “mystery” clients, clinical vignettes, provider knowledge tests, and review of medical records but there is little published information on the validity of these methods or how these tools capture the construct of quality practice.5 Simulated clients (SCs) are hired staff trained to adopt a case scenario of a fictional client and then present to a provider for care, ideally without the provider knowing they are being evaluated at the time of the consultation. SCs can generate an accurate measure of routine provider quality behaviors but implementing SCs can be difficult in LMICs. Simulated clients require intensive training to effectively adopt the persona of a client and accurately report details of the consultation, and field visits to remote, rural facilities can be expensive due to logistics and transportation.

Clinical vignettes (CLV) have been used for decades to measure health provider care knowledge.6–8 During a CLV, providers are given a case scenario and asked a series of questions about care they would provide. CLVs are thought to better estimate provider skills than knowledge tests because they are more practice-based. They record the provider’s response to a fictitious client similar to one that they might encounter during their everyday practice.6 Studies in the United States indicate that CLVs are an adequate proxy measure of physician quality practices but there is less information on their validity from LMICs, particularly for family planning.9,10 Unlike other quality of care tools, CLVs can be administered by mobile phone, eliminating field costs making them more feasible in settings where cost and infrastructure make field visits difficult.

To address the gap of information on the accuracy of low-cost quality measurement tools for LMIC family planning programs, we tested the validity of mobile phone-based CLVs for measuring quality contraceptive practices using simulated clients as a gold standard. We choose the simulated client protocol as the gold standard because it is a more accurate assessment of the provider’s routine quality care compared to direct observation, due to elimination of reactivity bias. We had the opportunity to test this as part of a larger quality of care assessment in Malawi.11 Close to 99% of the population of Malawi has mobile network coverage, ranked sixth in network access in Africa, making it feasible to test a mobile-phone based tool.12 If reasonably accurate, mobile-phone CLVs would be a more feasible, inexpensive alternative to SCs or other field-based assessments of provider contraceptive prescription practice in LMICs.

Methods

Sample

This sub-study was nestled in a larger cross-sectional quality of care assessment in six purposefully selected districts in Malawi.11 The aim of the overall study was to estimate quality of care for the districts and test the validity/reliability of several measurement tools. This sub-study focuses on the comparison of the CLV and SC tools. Districts were selected to represent an equal number of high and low performing districts based on outcomes including modern contraceptive prevalence rate, fertility trends, adolescent pregnancy, and unmet need for contraceptives. The study was a census of public sector clinics offering contraceptive services (n=112) in the six districts.

Tool development

The CLV tool was designed to mimic an actual consultation by presenting the provider with a description of a client they might encounter during their practice. It is meant to be more of a summative assessment – testing their knowledge and its application– rather than a formative assessment like a quiz. The interviewer began with a short description of the case scenario and the provider was invited to ask questions to gain more information. If the provider asked a relevant question, the interviewer replied with additional information from the case scenario. Providers were then asked about any physical exams or tests they would conduct, which contraceptive(s) they recommended, and what counseling they would provide. The tool was designed to be administered by mobile-phone.

Simulated clients were trained to adopt a standardized case scenario and attend the family planning clinics as an actual client, without revealing to the provider, staff, or other clients they were part of an assessment. We developed a checklist that documented the provider actions, and it was administered to the SC shortly after the visit by the team supervisor.

We developed two case scenarios based on Malawi specific contraceptive provider training materials.13–15 The SCs adopted the same case scenarios as was used in the CLVs. One case scenario was a married, adult client switching methods (referred to here as the “Adult” case scenario) and a second was an unmarried adolescent using contraceptives for the first time (referred to as the “Adolescent”) (Online Supplementary Document, Appendix S1). Each provider was evaluated using both scenarios per tool (i.e. 2 measurements per provider: 1 Adult and 1 Adolescent for both SC and CLV). The case scenarios, SC checklist and the mobile-phone based CLV tool were pre-tested with non-study contraceptive providers in Malawi to improve cultural and clinical relevancy. The genericized tools used in this study are available online.16

The CLV and SC tools captured the same quality information: the questions asked while taking client medical and contraceptive history, information given during counseling, exams or tests administered/recommended, and the contraceptives recommended (table 1). Both tools were used on the same provider to facilitate a direct comparison. Because the case scenarios for the SC and the CLV were the same, the CLV tool was administered at least three weeks after the SC visit allowing the provider to forget the details about the SCs.

Training and data collection

We trained local data collectors on the study protocols, how to administer the CLV tool and conduct the simulated client method. All data collectors were staff hired and trained for the quality of care assessment and had previous experience with household or facility surveys. SCs were chosen based on their willingness and ability to effectively employ the case scenarios. To simulate actual clients, SC data collectors were trained to provide the information from their assigned case scenario when asked by the provider. For their own protection and safety, they were trained to avoid all clinical procedures including receiving any injectable/inserted contraceptives, tests involving specimen collection, vaccinations, and vaginal exams. They could only accept pills or condoms and were trained on exit strategies in case the provider advocates for other contraceptives (Online Supplementary Document, Appendix S1). A different group of data collectors was trained to administer the CLV tool via mobile-phone, including approaches for contacting providers who worked in poor cellular network areas. As part of their training, data collectors practiced administering the CLV tools via mobile phone to non-study clinicians, and the SCs practiced presenting to non-study clinics, with contraceptive providers unaware they were SCs.

Field-based data collection was carried out from January through March 2018 followed by the mobile-phone based collection carried out from February through May 2018, a minimum of three weeks after the field visit. Both the adult and adolescent SCs arrived at a facility on the same morning, traveling separately, during the clinics normal operating hours. The provider who was providing care on the day of the SC visit was enrolled in the study. When each consultation was complete, the SC returned to a meeting point (out of visual range from the clinic) to be interviewed by the study supervisor, documenting what occurred using the SC checklist. Further details on the SC training and data collection are available elsewhere.11 The supervisor then returned to the clinic to interview providers on their background characteristics, education, professional status, and collected the best mobile phone number to reach them for further assessment. A minimum of three weeks later, as noted above, the data collectors called the same provider to administer the mobile phone-based CLV. If they could not initially reach the provider, they used several tactics to improve response rates such as varying the times/days of phone calls, sending a SMS to set an appointment for the call, or sending a verbal message through their colleagues that the research team was attempting to contact them.

Ethics considerations

We developed a listing of the names and mobile phone numbers of all facility-based contraceptive providers by contacting the in-charges at each facility. Using that listing, the data collectors called all providers on the list to obtain verbal informed consent. During the informed consent process, providers were told SCs would visit them at some point over the next three months, and they would receive a follow-up phone call. Approval for human subjects research was obtained from the National Health Science Research Committee in Malawi and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in the United States.

Analysis

We reported the background characteristics of the enrolled provider and summarized the CLV and SC for the provider behaviors (Table 1). We calculated the p value of the difference between the CLV and SC behaviors, accounting for clustering at the provider level (two measures per provider for both CLV and SC). For the validity analysis, we calculated the percent agreement, sensitivity, specificity, and the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUC) the adult and adolescent case scenarios individually and combined. We conducted a bootstrap analysis to generate 95% CIs for AUC, and used the Stata svy command for the sensitivity and specificity 95% CIs that take into account the clustered data (2 case scenarios per provider).21 The AUC represents the probability that a particular test correctly rates one “positive” subject and one “negative” subject that are randomly chosen and therefore summarizes the overall validity of the test.22,23 Following convention, we only reported the validation analysis for indicators with sufficient sample size, a sample of five or more in each cell of the 2x2 table.22 We used Stata 14 for the analysis, and a user-generated STATA program to calculate AUC.24,25 To account for missing data due to non-response from the mobile-phone CLV interviews, we performed an imputation analysis with two scenarios: assuming perfect agreement between the CLV and SC measurements, and assuming perfect disagreement.

Results

A total of 224 SC consultations were completed with 112 providers (two SC consultations per provider) and interviewers attempted to call all 112 providers for the mobile phone CLV (Figure1). During the SC protocol, 12.5% of the consultation data were missing due to lost data collection forms (n=2) or the SCs were not seen by providers because the clinic was closed during normal operating hours (n=5), or they were refused care because they did not consent to clinic procedures (n=24) as described elsewhere.11 Interviewers were unable to reach 12.5% (n=13) of the providers by mobile phone due to poor network (n=11), lack of mobile phone (n=1) or refusal to participate further (n=1) (Figure 1). A total of 85 providers or 170 SC consultations (75.9%) were matched with CLV data and used in the validity analysis (Figure 1).

Background characteristics

Providers were equally distributed by sex, 40.5% were under the age of 30, and most were married (62.9%), and predominantly Protestant Christian (76.4%) (Table 2). Most providers assessed were nurses or midwives (59.6%), 21% had been at their positions less than one year and 30.3% were community health workers known as Health Surveillance Assistants (HSAs), who also provide services in facilities. There were no statistically significant differences in provider socio-demographic characteristics between health providers who participated and those who did not (data not shown).

Methods recommended

The given preference for the case scenarios in both SCs and CLVs was pills. Most providers recommended pills to the simulated clients (81%, 95% confidence interval, CI=71-87%) and only half recommended pills during the CLVs (49%, CI=41-56%) (Figure 2). Providers recommended condoms more often during the CLV (54%, CI=46-61%) than in the SC (22%, CI: 15-31%) (Figure 2). During the SC consultations, providers recommended fewer methods overall (2.2 methods on average per client) compared to the CLV (3.7 methods).

Client history, clinical assessments, and counseling

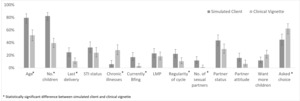

The questions the provider asked while taking client history differed by SC and CLV as well (Figure 3). The proportion of providers who asked the client about her age, number of children, last delivery date, whether she was breastfeeding, the regularity of her menstrual cycle, and number of sexual partners was statistically significantly higher during the SC compared to the CLV responses for the same scenarios (fig 3). A higher proportion of providers said they would ask about chronic illnesses (28% during CLV vs. 6% during SC; P<0.01), and the client’s preferred method on the CLV compared to the SC (62% during CLV vs, 45% during SC; P<0.01) (Figure 3).

Overall, the providers recommended more clinical assessments during the CLV compared to the SC (Figure 4). However, during the SC consultations, more providers recommended human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing during the SC compared to the CLV (15% vs. 4%, P=0.01). Counseling did not differ between SC and CLV, except for “what to do if pill was not taken on time or forgotten” (59% vs. 26%; P<0.01) (Figure 5).

For the indicators with sufficient sample size to conduct the quality analysis (n>5 in each cell of the 2x2 table), quality measured by CLVs was essentially a random guess as to what the provider did with the SCs (AUC not statistically significantly different from 0.5) (table 3).

Difference between adult and adolescent case scenarios

The pattern of differences between provider behaviors reported in the CLV and documented through the SC was similar for adult and adolescent case scenarios as in the combined analysis with these few exceptions (Online Supplementary Document, Appendix S2). In the adult case scenario, the proportion of providers who asked about age, last delivery, regularity of menstrual cycle, and currently breastfeeding was statistically significantly higher during the SC consultation compared to what they reported during the CLV. During the CLV, the providers reported more frequently that they would counsel the adult SCs on pill use and side effects compared to the SC consultation (Online Supplementary Document, Appendix S2) and this difference was not found for the adolescents. HIV testing was recommended by a higher proportion of providers during the SC consultation than during the CLV for the adolescent case scenario only.

Discussion

This study shows that skills and knowledge reported during a mobile phone-based CLV interview are not an adequate proxy of practice measured during a SC consultation, even when comparing the same client case scenario. Generally, our findings are in line with previous research on the validity of CLVs in LMICs. In Tanzania, a study found that CLVs did not correlate to the provider’s practice as observed by an assessor for care of fever, cough, and diarrhea-related illnesses.26 Two studies in India compared CLV and SC for child health illness and tuberculosis consultation (respectively), and found higher quality knowledge reported during the CLV compared to practice.27,28 Another study in Ethiopia compared CLV and direct observation as measured through a facility survey and also showed higher quality knowledge compared to the observation for childhood illnesses.29 In the Ethiopia study, two of the quality indicators were higher for the direct observation compared to the CLV by 30+ percentage points. None of these studies replicated the same case scenario for knowledge versus practice assessments or measured quality of care for contraceptives.

In this study during the CLV, providers reported recommending more assessments, asking about chronic illnesses, and recommending more methods than was reported in the SC consultation. Anecdotally, data collectors reported that the providers had more time to think about their responses during a CLV as compared to the SC, which took place in a busy clinic setting. The providers also knew the mobile phone CLV was an assessment but (ideally) did not know they were being assessed when the SCs visited for care. The higher proportion of quality behaviors reported during the CLV could be an example of the “know-do” gap or the difference between what the provider knows and what they practice.30 We did not document why the providers did not carry out these quality behaviors in practice but high caseload, poor availability of supplies, and provider motivation are all factors thought to contribute to the know-do gap and this could certainly be the case in Malawi where the health system is overburdened and under-resourced.17,31

However, providers performed some quality behaviors more often during the SC consultation than they reported during the CLV. They asked certain client history questions more often such as age, number of children, regularity of menstrual cycle and others (Figure 3). They were statistically significantly more likely to recommend the client’s preferred method (pills) compared to the CLV (Figure 2). Something about the clinic environment, being presented with an actual client, or non-verbal cues stimulated the providers to remember more quality procedures compared to the CLV for some aspects of quality of care. We assessed whether the providers used job aids during the CLV and most did not: 30.6% preferred not to use them and 63.5% said they did not have any job aids. It could be that for some of these behaviors, the providers did not recognize it as a “quality” action and therefore did not report it during the CLV, although it was done in practice. There could also be some bias with the mobile phone administration that could be eliminated if the CLV were administered in person. For instance, network problems may make it difficult to understand some of the questions or providers may want to hurry the interview to save phone battery. Either way, this is evidence that the mobile phone CLV may not accurately measure all aspects of knowledge.

When stratified by adult and adolescence case scenarios, a similar pattern of differences was seen between SC and CLV responses for most indicators. More differences were observed in the adult case scenario although no clear pattern emerged: a few indicators were higher during the SC while other were higher for the CLV. In general, the adolescent simulated clients received more complete counseling (Online Supplementary Document, Appendix S2) which lowered the discrepancy between SC and CLV. Some client history questions were asked less frequently during the adolescent SCs– such as regularity of menstrual cycle and timing of last delivery, which also made them less likely to be discrepant as well. These differences show that providers alter their counseling strategy to match the client profile, as might be recommended. Future quality of care assessments should take this into account.

This study had several important limitations. The SCs may have presented their scenarios in an unstandardized manner or mis-remembered or mis-reported provider-client interactions. For instance, SCs were trained to request pills as a method if asked but in some situations, they may have offered their preference for pills without being asked. Audio-recording of SC consultations is an option for future studies that could help ensure that presentation and reporting are consistent. The providers may have detected the SC and altered their behaviors during the consultation, although we had no indication of any unmasking during data collection. SCs could only request pills or condoms, which may have triggered suspicion since less than 5% of married, Malawian women use these contraceptives.32 SC were trained on exit strategies to avoid all clinical procedures such as blood draws and cervical exams and documented if the exam was recommended, even if they refused, so we were able to compare to the CLV results. This could have resulted in providers recommending a non-hormonal contraceptive such as condoms, since the providers could not do a full assessment. Per the exit strategies, the SCs were trained to say they would come back later for the exam and ask for a short-term supply of pills in the meantime. Most of the providers provided pills (81%) even without doing a full assessment (Figure 2).

Providers may have also altered their behaviors based on facility stock-out of contraceptives or supplies. We did not collect data on stocks or other elements of structural quality during the assessment. Another limitation of the study, the level of missing data (20%) due to non-response for the phone-based interview and/or SC being refused care at the clinics may have impacted the validity findings if the bias were differential by provider characteristics. However, we found no statistically significant differences in provider characteristics between those with missing and non-missing data and consider risk of this bias being differential to be minimal. The imputation analysis for the indicators in table 3 showed a qualitative change for all the indicators using the maximum disagreement method and for one indicator using the maximum agreement method, expected since the proportion of missing data is high (data not shown). Since we measured no statistically significant agreement for any of the indicators, we believe that despite the missing data, our conclusion is still that CLVs do not measure quality of practice the same way SCs do.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that mobile phone CLVs are not an accurate proxy measurement of provision of quality contraceptive care relative to SCs for public sector facilities in Malawi. The proportion of providers saying they would perform specific actions through the CLV was higher than the proportion captured by the SCs. This is also known as the “know-do” gap and has been found in other resource-constrained health care settings. Conversely, a higher proportion of health providers conducted more complete client assessments and recommended the preferred contraceptive compared to what they reported during the CLV, evidence that CLVs conducted via mobile phone may not accurately capture all knowledge. We hypothesize that being presented with a client in their clinical setting may stimulate them to remember more quality actions compared to a theorical case scenario described in an assessment setting. Although other studies in LMICs report poor validity of CLVs, more research can be done on improving CLVs so that they may be a better proxy of practice.

Phone-based protocols or other digital health solutions can make quality of care easier to monitor in facilities that are remote or rural, difficult to access due to geography or conflict, or during a global pandemic when social distancing is required.33 This study provides important information on the validity of quality of contraceptive care measurements where there is currently little information, especially for mobile phone-based methods. Continued efforts are needed to identify and test innovative methods to accurately and inexpensively measure quality of care to inform improvement of provider performance.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the technical inputs of Director Fannie Kachale, Deputy Director Henry Phiri, Mary Phiri, John Chawawa, Alufeyo Chirwa, Samuel Kapondera, Ndindase Maganga, Nelson Mkandawire and Lily Mwiba of the Reproductive Health Directorate, Ministry of Health Malawi; Peter Mvula, Winfrey Chiumia, Martin Joshua, Prince Manyungwa, Paul Mwera, Christina Mzunzu, and Flora Salamba of Wadonda Consult Limited; Khumbo Zonda of Marie Stopes International; and Amy Tsui, Scott Radloff, and Stella Babalola of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. We acknowledge the contributions of Ephraim Chirwa (listed among authors) who sadly passed away in July 2019.

Funding

This study was funded by Global Affairs Canada through the Real Accountability: Data Analysis for Results project.

Authorship contributions

EH originated the idea for the study, lead the study development, implementation, analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper, with MM contributing to the writing. DM, EC, PM, JK, and MM significantly contributed to the study development, implementation, analysis, and conclusions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available upon request from the corresponding author), and declare no conflicts of interest.

Correspondence to:

Elizabeth Hazel, PhD

Room W5504, 615 N Wolfe St, Baltimore, MD 21205 USA

_consultation_and_the_phone-based_c.png)

_recommended_during_the_simulated_client_consultation_and_the_cli.png)

_consultation_and_the_clinical_vignette_intervi.png)

_consultation_and_the_phone-based_c.png)

_recommended_during_the_simulated_client_consultation_and_the_cli.png)

_consultation_and_the_clinical_vignette_intervi.png)