Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) accounted for about 66% of global maternal deaths in 2017.1 The maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in Nigeria stood at about 917 per 100,000 live births with 67,000 maternal deaths, ranking 4th in the world after South Sudan, Chad and Sierra Leone.1 Therefore, addressing maternal mortality in Nigeria is a global priority and findings from research in Nigeria may inform an understanding of other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with similarly high MMRs.

Facility-based delivery (FBD), also known as Facility-Based Birth (FBB) consists of skilled care provision provided to pregnant women during delivery at a health facility and this is an important intervention for reducing maternal deaths.2 The Nigeria National Demographic and Health Survey 2018 observed that only 39% of Nigerian women gave birth in a health facility.3 This may explain why the MMR of Nigeria has remained high, thus contributing to high global maternal deaths.

Qualitative research is well placed to explore how women perceive factors that influence their choice of where to give birth. Qualitative evidence synthesis (QES) applies the principles of systematic reviewing to studies that use recognised methods of qualitative data collection and qualitative data analysis – studies are systematically identified and assessed for quality. Extracted data are then synthesised to derive insights into the perspectives of service users and their decision-making processes. A previous QES was conducted by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the World Health Organization (WHO) to analyse the barriers and facilitators to FBD in LMICs.4

The USAID/WHO review offers a useful framework against which to map the factors affecting FBB in LMICs. However, questions remain regarding the extent to which synthesised findings apply to specific countries or contexts. For example, the USAID/WHO review included only two qualitative research studies conducted in Nigeria.5,6 Experience from conducting another country-specific review (i.e. Kenya) in this topic area7, and from two Masters assignments based on Nigerian studies done at the University of Sheffield, suggested that the two included studies may represent significant under-reporting of the eligible qualitative evidence. These initial projects were conducted by the first two authors and supervised by the third author which later informed the conceptualisation of this review. Therefore, this QES aims to increase the coverage and richness of included studies while focusing on specific considerations relating to FBB in a Nigerian context. This review uses common factors identified from the original USAID/WHO review as a “best fit framework”8, supplemented by factors unique to Nigeria.

Evidence syntheses that have addressed the low uptake of FBB have tended either to be quantitative9 or to assimilate evidence from different geographical regions or countries.4,10 This “context-specific QES”11 aims to explore the factors influencing the use of FBB in Nigeria. The specific objectives of the QES are:

-

To explore the various facilitators and barriers that influence the utilisation of services to support FBB for pregnant women in Nigeria.

-

To provide recommendations for policymakers in Nigeria on strategies to strengthen the utilisation of services to support FBB.

METHODS

Methods for QES have been developed by the international Cochrane Collaboration12 and have received substantive endorsement by the WHO.13 They are recognised as making an important potential contribution to an understanding of the effectiveness of programmes, by increasing understanding of a phenomenon such as FBB, identifying associations between the broader environment (e.g. urban and rural Nigeria) within which people (pregnant women, fathers and other community members) live and programmes are implemented, and unpacking the influence of individual characteristics and attitudes (to both birth and health facilities).12 A sensitive literature search seeks to identify as many relevant studies as possible, examining and rejecting many abstracts in ensuring that items are not missed.14 Typically, all studies that pass this initial test of relevance and that can potentially contribute to the overall interpretation are included within the review; quality assessment is used to moderate the certainty associated with each finding, not to exclude suboptimal studies. A QES concludes by acknowledging the limitations of the review methods and of the included studies, which act as constraints associated with secondary analysis of already published data.

As this synthesis follows recognised QES methodology, a systematic review protocol was produced to allow a priori specification of review methods, to facilitate replicability and to protect against potential threats to rigour. This secondary research is based on already existing published data with no participant involvement and therefore ethical requirements were not applicable.

Literature search

Searching for qualitative studies is widely recognised as problematic, primarily due to variations in terminology and limitations in subject indexing.14 Debate continues within qualitative evidence syntheses regarding the acceptability of alternative sampling approaches.15,16 However, in this case, the specific country focus indicated that it would be both feasible and useful to use a comprehensive exhaustive sampling approach. We used recognisably relevant references as a starting point for potential free text and thesaurus search terms. This strategy known as “pearl-growing” involves reviewing all terms assigned by authors or indexers to the relevant record, identifying whether they are sufficiently distinctive and, if so, adding them to the formal search strategy.17

Initial searches were conducted on MEDLINE via OVIDSP, EMBASE via OVIDSP and CINAHL via EBSCO between March 2017 and April 2017 and were limited to articles published from 2000 to 2017. The inception date of 2000 was chosen to reflect the likely influence of Millenium Development Goal campaigns on health services. We undertook a further search in MedNar and the Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health (NFMOH) websites to identify grey literature. Update searches were conducted in June 2019 using PubMed MEDLINE and an update citation search was also done in the same period. Citation searches were conducted for all included studies to identify additional studies. The full electronic strategy for Ovid MEDLINE is presented in Appendix S1 in the Online Supplementary Document. Boolean operators were used to combine sets across the SPICE elements (Table 1).18

Studies were limited to those published in the English language. Report types could potentially include journal articles, book chapters, grey literature reports and academic theses provided that they reported a full account of a qualitative research study. Abstracts and conference proceedings were excluded, given their acknowledged tendency to report incomplete information.19

Methodological filters designed to retrieve qualitative research were used to optimise the likelihood of identifying potentially relevant studies.20

Citation searches

Citation (reference) searches were conducted on Google Scholar for all included papers (forward chaining). 192 citations were reviewed for additional included studies while 290 citations were reviewed from the update citation search. The reference list of each included study was reviewed for relevant references.17

Searches of the repositories for major Nigerian universities were also conducted and yielded one additional thesis. Two further eligible theses by Nigerian students registered at South African and United States universities were identified from the Google Scholar search.

Study selection

Study selection was completed by two independent reviewers with each reviewer independently assessing each article using the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2). Titles and abstracts were reviewed sequentially and those meeting the inclusion criteria, or those with insufficient information for exclusion, were referred for full-text inspection. In the absence of consensus, articles were referred to a third reviewer.

Data extraction

Data extraction of included articles was performed simultaneously with a risk of bias assessment using a Microsoft ExcelTM spreadsheet, adapted from previous systematic reviews and modified following pilot extraction. Each of the two principal reviewers extracted data independently from a separate set of studies. A third author checked the extracted for accuracy, completeness and resolved discrepancies that arose from the two reviewers. Data items included SPICE elements, descriptive study characteristics (objectives, study design, data collection, analysis method, ethical approval), themes identified from a pre-existing framework and conclusions.

Qualitative findings, in the form of author observations on the data, may appear throughout a paper. However, in this instance, we privileged extraction of findings from the Results sections alone of the included primary studies reasoning that subsequent sections should draw upon salient findings from the Results section. Verbatim quotes and accompanying author’s interpretation were all extracted as data with quotes documented as italics and authors’ interpretation documented as bold. By combining these sources, we sought to obtain the authentic experiences of participants enhanced by the researchers’ interpretation of context and significance.

Risk of bias assessment

No accepted methods exist for assessing the risk of bias for qualitative studies.21 The team, therefore, privileged a structured examination of study quality using the most commonly used quality assessment checklist; the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist tool.22 We rated each study as being of high, moderate or low quality. No article was excluded from synthesis because of study design limitations.21 Following accepted approaches to interpretive reviews, we prioritised the contribution of each study to answering the review question and to the overall interpretation over technical criteria for data collection and analysis.

Methods for assessing the likelihood of publication or dissemination bias in qualitative studies are relatively underdeveloped, although such biases undoubtedly exist.23 For example, “truncation bias” occurs where the full reporting of results is constrained by journal word limits. We sought to mitigate against potential truncation bias by seeking academic thesis reports that met our eligibility criteria, even where journal versions of the same study also exist. We identified one thesis from our search of Nigerian university repositories and two additional theses by students registered at non-Nigerian universities.

Synthesis

Findings were synthesised using framework synthesis.8 Best fit framework synthesis is recognised as a rapid and efficient way of generating themes; initially deductively and then through a discrete inductive phase to analyse the remaining data. Framework synthesis is one of several options believed to offer deliverable findings that are easier for policymakers to apply to their context.24 While thematic synthesis offered a flexible and easily understood alternative, we selected a “best-fit” framework synthesis approach to optimise comparison with a framework derived from a pre-existing multi-context qualitative synthesis on FBD for LMICs (Table 3).4

The authors agreed on a reflexive statement to acknowledge their positionality concerning their perceptions of FBB and the possible impact it could have in the synthesis of the study. All the authors generally favour formal interventional approaches to support a pregnant woman during birth that will give rise to the outcome of a healthy mother and baby. Two of the authors have varying practical knowledge and experience of the Nigerian context while the third has little. This imbalance helped to constrain the unwarranted interpretation of the findings.

Reporting

This systematic review is reported using the ENTREQ statement guidelines outlined to adhere to the comprehensive and transparent reporting of QES.25

RESULTS

Search outcome

A detailed search across the included databases including citation search yielded a total of one thousand four hundred and thirty studies (1,430) (Appendix S2 in Online Supplementary Document). Following removal of duplicates, 1084 records were eligible for title and abstract screening. 1054 items were excluded following the examination of title and abstracts. Full texts of 30 items were examined. Twenty-seven eligible studies were identified and included in the qualitative evidence synthesis after 3 articles were excluded with reasons (Figure 1) and Appendix S3 in the Online Supplementary Document shows the 3 articles excluded with reasons. Table 4 describes the characteristics of each of the 27 included studies.5,6,26–50

Quality assessments

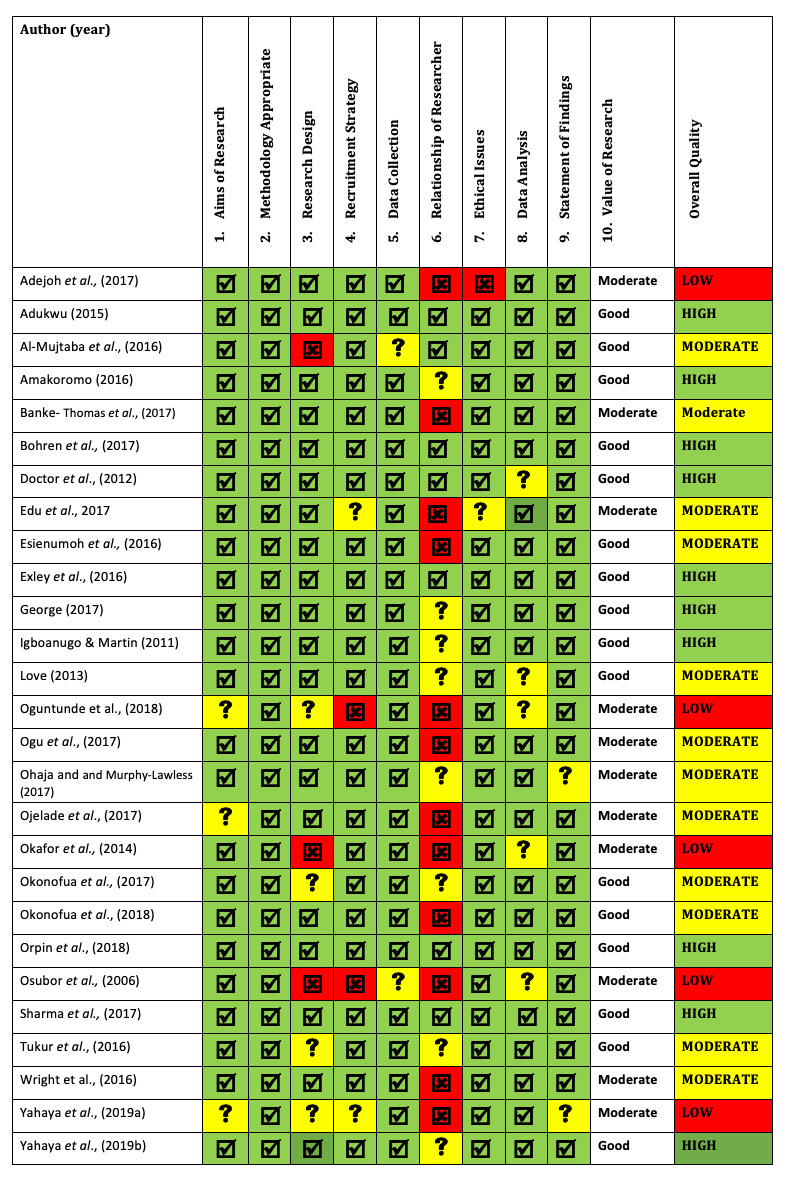

All twenty-seven studies were assessed using the CASP checklist for qualitative research (Table 5). This was independently assessed by two reviewers and conflicting results were resolved by the third reviewer. One source journal was considered a potential predatory journal37, two other journals are controversially labelled as such28,33 and the studies included three academic theses.27,29,35 The remaining journals are indexed in PubMed MEDLINE.

Themes

Data were organised under four overarching themes in line with the best-fit framework used for this synthesis.4 Further synthesis gave rise to two or more subthemes (Table 6). Details on the results of the included studies can be found in Appendix S4 in the Online Supplementary Document.

Perceptions of pregnancy and childbirth

Compelling reasons for giving birth in a health facility were a woman’s prior experience of a safe delivery or other women having given birth safely.35 Also, “an additional attraction going for facility delivery was the incentives given to patients such as baby kits and mosquito nets.”47

Childbirth was consistently revealed as a normal, safe process6,38 leading to a prevalent narrative that a facility is only to be accessed when a woman developed complications. Another prevailing fear that related to the medicalisation of childbirth was that, “Some of the participants complained bitterly for fear of sharp objects and recommendations for Caesarean Section.”29

Conversely, a woman’s knowledge of their HIV-positive status encouraged them to pursue FBB.28 However, another study elicited opinions that the requirement to undergo an HIV test “drives women away from using the facilities.”43

The home environment offers a competing private and comfortable place for birth compared to the open nature of health facilities.47 For example, some traditionally prefer to lie on the floor to have their babies whereas midwives in the hospitals may try to persuade them to deliver on a couch.33

Influence of sociocultural context and care experiences

Sometimes choice may be determined by whether the partner is available to transport her to the clinic.28 Husbands were typically the major decision-makers in the household.35,46 However, this influence may extend to the husband’s family: “My sister’s husband told me to go to the TBA although my husband did not support the idea. However, I had to obey my sister’s husband by going to the TBA for care.”33

Nonetheless, family influence is not always construed negatively; a mother advocating FBB to her daughter35 or a husband affirming his wife’s choice35 were viewed as an extremely positive occurrence. Friends also influence the place of birth, particularly if their own experience has been positive.35 TBAs also play a positive role where they perceive danger signs associated with delivery.38

Religious leaders are seen to play important roles in signalling the need for FBB services.38 The influence of religious belief is also seen less overtly in shaping how the overall labour and birth takes place. Adejoh et al26 reported that, “…Even when lives are lost in the process of giving birth in religious homes, they see it as 'the will of God”.

The women cited the sudden onset of labour as a reason for not giving birth in a facility: which didn’t give them time to plan: “It was the hospital [where I] intended to give birth, but it [labour] suddenly come at home, before I could come, I felt I cannot make it, so I delivered at home.”34

Resource availability and access

Participants voiced practical concerns relating to the availability of, and access to, health facilities; for example, the working hours of the facility47 or delays experienced when waiting to access services.

FBB is seen as expensive37,40 and this may influence women to resort to home delivery35 and to access TBAs as a cheaper option.29 Women expressed the view that if the facilities were free then women would utilise the services.47

The sudden onset of labour may preclude transportation options, for example, the use of motorcycles or Okada (motorcycle taxis).29 Okada may even drop the nurse at the facility before returning for the woman.37 If nearby facilities are closed women need transportation to more distant facilities.46

Some communities benefit from Emergency Transport Schemes (ETS) that have been instituted to transport pregnant women to the hospital. However, some health facilities do not readily admit women brought by the ETS drivers because the drivers are not able to identify themselves as volunteer drivers for the program.38

Women who used the program and their husbands responded positively to ETS as they affirmed that, "It [ETS] has really helped women. Immediately we get to know that a woman is in labor and she is bleeding, we immediately call the driver to come take her to the hospital […] yes, it is a success." (Woman, integrated ETS, Kaduna)38

Security challenges were identified as a significant barrier, given that drivers often transport the women at night.

“I won’t forget [the experience] of one of my drivers that once took a woman in labor to the health facility […] in the night. Thieves attacked them on the way, forced them to stop [..], laid them flat on the ground and they collected the little money that the woman’s husband had on him.” (Focal person, integrated ETS, Kaduna state).38

Other transportation-related barriers from the same study included insufficient numbers of volunteer drivers and vehicles, poor road conditions, and instances where a husband would not let the driver transport his wife which often led to sad outcomes38 - “All in all she was not taken away from home, she died while we were trying or in the process of looking for car” (MD-6).46

Perceptions of quality of care

Women frequently expressed concerns about the lack of privacy.31 In some cases, this not only threatened basic human rights but also transgressed religious dictates.31 A particular concern was where women were managed by male staff, against the preferences of husbands, the women themselves or both.

Again, such sub-standard care is uneven with other women expressing appreciation for the standards of the facilities and the availability of medicines and equipment. Women would also contrast past and current standards of cleanliness, praising such improvement.34 They would also contrast unfavourable treatment in previous facilities with favourable staff behaviours and attitudes.35

Women may be suspicious of facilities if they believe that they will be insulted or poorly treated.31 Other studies corroborate this finding, including instances of women being slapped by health staff or yelled at for not bringing in supplies or not complying with health provider demands.41 Further lack of trust was seen in the belief that healthcare workers will swap their babies with a dead baby.32

Other policies and procedures, separate from mandatory HIV testing, also exerted an influence over the choice of place of birth. These can operate in either a “push” or “pull” direction. For example, TBAs may not readily refer women with complications to hospital Instead they may use the health facilities as a place of last resort once they have exhausted other options.35

DISCUSSION

Implications for Nigeria

Given that FBD is considered expensive there is a need to explore different funding options. These funding options may include a need to review delivery fees either in form of a discount, health insurance package or a free service especially for women residing in rural areas.51

Poor access to health facilities, identified either as lack of transportation services or bad condition of the roads, constitutes a major challenge to women residing in local areas. This has made the women settle for other alternatives that are close and convenient. It could be argued that a lack of health service proximity particularly exists for rural Nigeria. This highlights the urgency to address rural-urban disparities in Nigeria. ETS interventions, designed to improve pregnant women’s access to health facilities, offer a response in many underserved communities. In northern Nigeria, these schemes have required collaboration between government departments, development partners, and transport unions with various donor-funded projects providing scale-up within the region.38 However, our review identified reported difficulties in being admitted to facilities when transported by an ETS driver, leading to a recommendation that ETS programmes ensure that drivers are provided with identification to facilitate prompt admission

The utilisation of FBD services in Nigeria is deeply influenced by widespread socio-cultural determinants, diverse perceptions and experiences. These sociocultural factors are influenced by anecdote and stories which can operate either positively or negatively which can be used as a tool for change. Changing negative perceptions can be achieved through the institutionalisation of the Safe Motherhood Action Groups (SMAGs) which are community-based volunteer groups that seek to address knowledge gaps and change long-held perceptions. Studies of SMAGs from Zambia have demonstrated the relevance of this intervention in improving institutional births in poor rural settings.52,53 The SMAGs are particularly effective when the volunteers are indigenous beneficiaries of facility delivery. A similar community-based volunteer group called Voluntary Community Mobilisers (VCM) has been used, particularly targeting childhood immunization, in some states in Nigeria.54 The VCM were found to be instrumental in improving immunisation uptake. Such policy implications may extend to FBBs for pregnant women in Nigeria.

This review identified in passing that the prospect of gifts for women after delivery may further shape the perceptions of women and their subsequent choice of place of birth. This incentive was found to be a cost-effective way of increasing facility delivery in rural Zambia.55

Implication on the three-delay model

In 1994, Thaddeus & Maine proposed a “three delay model” against which to define interventions that address maternal mortality. The first delay relates to the 'decision to seek care’. The second phase constitutes’identifying and reaching the medical facility’. Finally, ‘receipt of adequate and appropriate treatment’ is required. In subsequent years, the three delays model has emerged as an important visualisation of challenges faced in delivering FBB and has been a relevant framework particularly in LMICs. Our QES offers an amplification to certain social factors that complement these delays and a conceptualisation, which reveals a complex interplay of factors, of which lies a pregnant woman at the centre who is continually subject to influences. So, an otherwise predetermined decision may be modified by situational factors, such as the sudden onset of labour, by actual or presumed experiences of the mother or influential others, or by available resources (such as the availability of transport). Others have previously led the critique of the three-delay model such as Sorensen et al56 in their work in Tanzania

As an alternative, we propose a relationship between four broad themes which, if addressed, should lead to greater participation in FBD and improve overall maternal mortality indices. These four themes are adapted from the four overarching themes presented in the result section (care quality, resource availability and access, influence of sociocultural context and care, and beliefs and perceptions of pregnancy). The fourth of these factors, relating to the woman’s beliefs and perceptions, based on actual, vicarious and assumed experience acknowledges the unique contribution of qualitative research and places the woman at the centre of decision-making.

Implications on wider similar contexts

Comparison of findings from this QES with the multi-context review funded by the WHO4, and with a single country QES for Kenya7 co-produced by one of the authors, reveals some interesting insights. At a mid-range level, the same constraints pertain across geographical and cultural contexts; for example, how the availability of genuine choice is limited by the rapid onset of labour or by the occurrence of obstetric emergencies. Specifically, however, transport options may differ across countries and arrangements for access to facilities may be organised differently. Prevailing religious beliefs may differ but the influence of religion, traditional beliefs and family attitudes typically combine to impact upon decision-making. Health staff may differ in their attitudes to the women in labour but respect for the women varies more by degree than by its importance. This review can therefore inform an understanding of the decision-making context within which FBB is contemplated and actioned in similar contexts but cannot replace the nuanced interpretation of these factors offered by qualitative research specifically from those contexts.

Methodological strengths and limitations

This context-specific qualitative evidence synthesis on perceived barriers to FBB in Nigeria demonstrates how concentrating study identification and analysis on a single context offers more studies, thicker contextual detail and a nuanced understanding of context, when compared to multi-context reviews (i.e. with included studies from multiple countries).11

One methodological concern is that multi-context reviews access a fraction of relevant evidence. The multi-context review4, a high-quality qualitative synthesis, only identified 2 studies from Nigeria. Our forensic efforts to identify additional studies by searching institutional repositories, by following up citations and by pursuing Internet pointers unearthed sixteen studies. Eleven (69%) out of these sixteen studies were identifiable from MEDLINE alone suggesting a trade-off between exhaustivity and informativeness for country-specific reviews. Importantly, 12 of these 16 studies (75%) have been published since the publication of the multi-context review. Use of a five-year-old multi-context review in decision-making may under-represent the evidence base, for one country alone, by a factor of eight.

Being a context-specific review, the findings of this synthesis may have limited generalisability to similar settings in SSA. However, the congruence of findings with the framework of the multi-context review4 suggests that similar issues influence the choice of place of giving birth in other regions.

Further work should further explore “relevance”. Noyes et al57 describe relevance as the extent to which data from primary studies is applicable to a context. Context here would mean the setting or population. Nigeria enjoys multiple tribes and ethnic origins represented by included studies. Detailed examination would reveal whether regions included in the review are homogeneous, for example, in health system infrastructure and government policies or heterogenous based on tribe, language group, religion and ethnicity. This will further drive the applicability of the review findings by policy makers in their respective settings and perhaps an extension to other LMICs contexts.

CONCLUSIONS

Addressing structural gaps in facility-based services alone is insufficient in improving maternal mortality indices in Nigeria. Wider social determinants, such as socio-cultural beliefs and care experience, operate as key factors to influence the utilisation of maternity health services. SMAGs offer one potential solution for addressing community-level factors identified in this review. Future research should be undertaken to determine their effectiveness and relevance in different contexts in Nigeria. In the meantime, FBD services, particularly in rural areas of Nigeria, continue to encounter gaps involving distance and access. We recommend that ETS should become part of standard service provision in such areas to address such inequalities.

This review demonstrates clear benefits from accessing a richer and more diverse set of qualitative studies for Nigeria when compared with a multi-context review that contains a mere fraction of includable studies. However, as previously stated country-specific reviews constitute an expensive resource and must be commissioned judiciously.

Funding:

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authorship contributions:

SM and CA did the preliminary search and protocol with a robust and update search done by AB. SM and CV separately did the quality assessments of the included studies with AB as the third assessor. All authors jointly did the data extraction and contributed in the draft write up and editing.

Competing interests:

The authors completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available upon request from the corresponding author), and declare no conflicts of interest.

Correspondence to:

Dr Suleiman E Mshelia MBBS, MPH (Sheffield), DiPM (UK)

Department of Community Medicine

Jos University Teaching Hospital

Plateau State, Nigeria

[email protected]