Excessive absenteeism and low retention of health professionals has resulted in high vacancy rates for doctors in rural health facilities.1 It was found that 58.5% of doctor’s-level positions are unoccupied at the rural health complexes,2 compared to an average of 39.45% of unfilled positions on average throughout Bangladesh.3 These statistics indicate an imbalance between rural and urban vacancies, showing more doctors working in the cities. Moreover, countrywide, the average absence rate of doctors is 58.75%.4

One of the main objectives of the health policy of Bangladesh is to ensure primary health care and emergency treatment for all.5 Still, primary health facilities are running short of adequate doctors. Chaudhury and Hammer6 identified two problems related to providing public health services in rural areas. One problem is the unwillingness of doctors to serve in the rural areas. They refuse offers of appointment or posting there or otherwise try to prevent being posted there. The other problem is that, even when the post is filled, ‘the provider often fails to show up’: i.e. they are absent. This paper will seek answers in economic theory, like rational choice theory and institutional theory, to questions like why doctors do not want to serve in rural areas and what the relationship of the policies and practices of the regulating authority is to the failure to get doctors into the rural health facilities serving.

Rural placement of doctors in Bangladesh

Very few studies have been done in Bangladesh regarding rural placement of doctors and none of those has attempted to use economic theory to enlighten the discussion. Most of these studies have used qualitative methods of data collection and analysis. The studies are narratives without the benefit of economic theory to explain what the respondents were telling the researchers. From that literature, we can find two broad themes: factors in doctors not serving in rural areas related to individual rationality and factors in doctors not serving in rural areas related to institutional constraints. The data related to rural placement of doctors in Bangladesh is presented in Table 1.

Rural placement of doctors in neighboring countries and beyond

The problem with rural service by doctors is not unique to Bangladesh as neighboring countries have similar problems. Rajbangshi et al.13 conducted research in India to identify motivations for, and challenges of rural recruitment and retention of health workers, including doctors and nurses. They found that health workers’ decisions to participate in rendering health care in rural areas is strongly associated with the health care worker’s own background and attachment to a rural community. On the other hand, the challenges of recruiting and retaining health care workers in rural areas included: poor working and living conditions in rural areas; low salary and incentives for service in rural areas; lack of professional growth and recognition opportunities for those serving in rural areas; and lack of educational opportunities for health care workers’ children in rural areas. Shortage of health care workers is considered to be a critical problem in rural Nepal.14 Shankar and Thapa15 conducted study on the medical students of Nepal to find out why the doctors were reluctant to serve in rural Nepal. They found that inadequate living facilities, low salary, less personal security than urban areas, less opportunity for professional development in rural than urban Nepal, and less health infrastructure are the main reasons behind health care workers’ unwillingness to serve in rural Nepal. Sultana et al.16 researched on willingness of doctors of Pakistan to work in the rural areas. They identified that lack of personal career development opportunity in rural areas, low salary, poor benefits and poor living conditions are some of the factors of unwillingness to work in rural settings. Besides, willingness of the lady doctors to serve in rural areas may depend on their spouses’ decision as well. According to Budhathoki et al.,17 lack of infrastructure, high workload, poor hospital management and isolation are some of the important factors that demotivate medical students to serve in rural areas in low-income and middle income countries. As Sri Lanka, Nepal, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan are in this category, this observation may also be applied to these countries.

Not only in the neighboring countries of Bangladesh, but also in other countries around the globe, doctors show similar attitudes to rural placement. Dewar18 found that medical education at urban areas in Australia induces to seek to continue their urban lifestyles. So even medical students coming from the country lost their connections with rural areas and ended up staying in urban areas as doctors. Sirili et at.19 studied retention of medical doctors at the district level in Tanzania. They found that, “unfavourable working conditions including poor working environment, lack of assurance of career progression, and a non-uniform financial incentive system across districts; unsupportive environment in the community, lack of opportunities to earn extra income, lack of appreciation from the community and poor social services” (p.1) are the challenges for doctors retention in districts.

Similarly, Asante et al.20 found that the inadequate budget for the health sector, lack of opportunity for career development, lack of supervision, inadequate infrastructure and logistics are the main challenges in trying to retain doctors in rural Timor-Leste. Whitcomb21 found that the failure of rural communities to provide career opportunities for doctors’ spouses and quality schools for their children make rural placement unattractive in the USA. Besides, doctors feel professionally isolated in rural communities after an initial period.

Yet there are contrary examples. In Pakistan, most of the doctors who have lived in rural areas are interested to practice in rural areas.16 The story in India is similar: many doctors are interested to go back to their own native villages to serve their own people.13 Another study11 on Bangladesh also found that being able to provide service to poor people is a source of motivation for the doctors. Laven and Wilkinson22 found, doctors with a rural background in Australia are about twice as likely to work in rural areas, than those with urban background.

Therefore, irrespective of country, whether developed or under-developed, it seems that doctors with rural backgrounds are willing to work in rural settings to some extent. This finding may be helpful for policymakers crafting policy to improve the supply of doctors in rural areas. Yet, rural areas in most countries are suffering from shortage of doctors and mostly for the same reasons. According to Wilson et al.,23 ‘‘Both developed and developing countries report geographically skewed distribution of healthcare professionals, favouring urban and wealthy areas, despite the fact that people in rural communities experience more health related problems’’ (p.1).

Theoretical aspects

Most of the literature we found did not attempt to explain the phenomenon of rural medical professional shortage with any theory. Hence, one of the objectives of this paper is to develop a theory to explain this problem. To develop such a theory, we hypothesise two broad independent variables: rational behaviour and institutional constraints. Rational choice theory can help us to explain why so many doctors do not choose to serve in rural areas or depart for the cities after they do. Institutional theory can help us to understand the constraints and incentives which making leaving rural practice a rational choice for the doctors who do so.

Rational behaviour

Here, rational behaviour indicates that individuals behave in such a way so that they can maximize their benefits subject to applicable constraints. Doctors are presumed to prioritise benefits such as income opportunities, family concerns, professional and personal development etc. as benefits of practicing medicine, which may be done in the country or in the city. Of course, we presume that the doctors will weigh the relative access to these benefits associated with each choice: country or city.

Rational choice theory

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoH&FW) of Bangladesh do deploy doctors to cities or to rural areas. Yet many doctors deployed to rural areas are found absent because they are practicing in the city. Therefore, the doctors’ preferences cannot be realistically ignored. Rational choice theory can help us to understand why doctors have these preferences and choose to practice in these ways. Rational choice theories explain an individual’s choice behaviour.24 Elster25 explained that the rational choice theory is a normative theory. It does not describe what should be the goal or objective of individuals: rather, it explains the means to achieve an aim or targeted objective by the individual. Coleman and Fararo26 show a relationship between individual’s rational action and institutional or social behaviour. They say that rational choice theory is fills in the connections between the micro level of individual action and the macro level of system structure. Here macro level can be described as the institutional structure, the Bangladesh health service and the micro level as the behaviour of doctors within the health service. According to Scott,27 in rational choice theories, individuals are posited to be rational beings who are motivated by their necessities according to their preferences. They act within specific, given constraints and based on the information that they have about the conditions under which they are acting. Then when individuals belong to an institution, their preferences may undermine their imposed duties if they act to maximize their utility. In the case of doctors’ choice between rural and urban placement, they may prefer the option that gives maximum benefits. Similarly, Sen28 showed the utility maximization process as ‘‘the result of conscious choice’’ (p.175). It means a person chooses an option deliberately to maximize his/her utility. Here, rational choice theory is used to explain how doctors make conscious choices between rural and urban practice to maximize their utility, based on the information they have, even if this undermines their imposed duties to the health service.

Institutional theory

North29 introduced institutions as ‘‘humanly devised constraints’’ (p.97) that shape political, economic and social interaction. He states that institutions contain both formal rules and informal constraints. Here, formal rules indicate constitutions, laws etc. and informal constraints consist of customs, tradition, code of conducts and so on. Therefore, institutions have some tools to control the behaviour of individuals. Hall and Taylor30 says ‘‘institutions affect behaviour primarily by providing actors with greater or lesser degrees of certainty about the present and future behaviour of other actors’’ (p.939). Therefore, it can be said that even rational behaviour of individuals can be controlled by the institution. If employees do not follow the rules of the institution and try to maximize their personal benefits by avoiding their stipulated duties, then conflict may arise between institutional goals and individuals’ goals. As this study investigated why doctors are not attending in or leaving their rural postings, because of institutional weaknesses or not, hence, this study used institutional theory to understand the impact of the health service constraints on the doctors and the impact of the doctors’ rational choices on the health service.

METHODS

Study design

A literature review was conducted by searching electronic databases and by manual search of the internet and physical books and journals in libraries. This study is broadly divided into two parts. Part I tries to understand the views of doctors towards rural placement both in Bangladesh and in other countries. In part I, we discover the challenges of placement in rural health centres as the doctors perceive them. We reviewed a wide range of literature (both physical and virtual) such as: journal articles, reports of different organizations, government policies, reports, circulars, office orders etc. We also collected data from different websites. Part II focuses on theory. We tried to explain the rural shortage of doctors using rational choice theory and institutional theory. We collected literature related to these theories from books, journal articles and empirical studies.

Search strategy

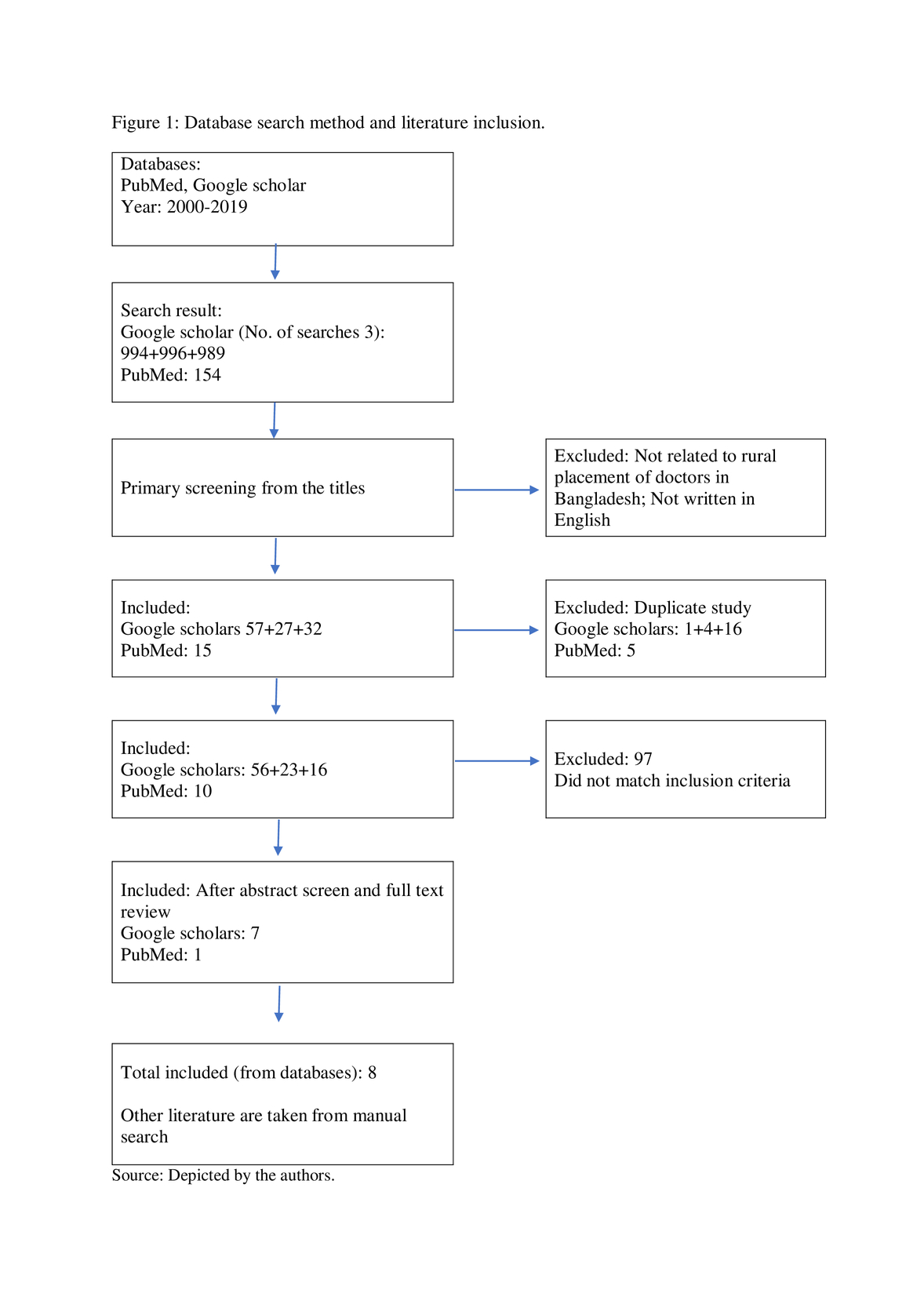

Two types of search method were used for this study: electronic database search and manual search. We have used PubMed and Google Scholar for electronic database search. Manual search was conducted through Google search engine. We conducted searches thrice in Google Scholar, with different search terms, to cover as many articles as possible. The search terms in Google Scholar were: ‘Rural placement of doctors in Bangladesh’, ‘Rural placement of doctors in Bangladesh AND Doctors Retention in Rural Bangladesh NOT Nurse NOT Patient NOT Disease’ and ‘Factors influencing doctors’ placement in Bangladesh’. The search term for PubMed was ‘Rural retention doctors Bangladesh factors’. We used a software31 for database search. We also sought further resources in the references of sources found by the above methods: snowball method.32

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Some criteria were set for electronic database search. This study included the literature published between the year 2000 to 2019. We excluded the books but the articles, reports and other documents were taken. We also did not consider literature not published in English. These criteria were not applied in manual search. To supplement the term ‘Rural area’, ‘Retention’, and ‘Doctors’, we also accepted ‘Underserved area’, ‘Absenteeism’ and ‘Health workforce’. From database search result, we have excluded the literature not related to Bangladesh. The details of electronic databases search and inclusion of literature is shown in Figure 1. As this study needed to examine the state of rural doctor supply in other countries, so we searched manually for the particular countries. As it is not possible to study all the countries, therefore we have considered South Asian countries, USA, UK, Australia and some countries from Africa. As the study used rational choice theory and institutional theory, for information about these theories we consulted books, journal articles and some empirical studies.

Data analysis

After getting the related literature, we thoroughly reviewed those and accumulated necessary data. Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis approach33 was used to analyse the data. Hence, this study followed the following steps: familiarizing the data, generating initial codes, searching, reviewing and naming themes; and finally producing the report. The findings are described in narrative manner as we collected qualitative data. Data sample size was considered too small to validly use quantitative method. Finally, the findings are explained by the theories we used in this study. No specialized software was used to analyse the data. Data analysis was done manually.

RESULTS

From the literature survey, it is clear that doctors perceive the benefits of practice in urban areas to be greater than the benefits of practice in rural areas, except perhaps for some doctors who themselves have rural roots. So, the rational choice for such doctors is to avoid duties in rural areas and maximise practice in city areas and they do so. Yet this rational doctor behaviour violates health service constraints. This is the basis of the conflict that leaves rural patients out in the cold. Why are the constraints not effective? In other words, why are the doctors the winners in that conflict with the health service? One answer found from the literature is that the institution failed to monitor or supervise the doctors and to provide adequate personal, social and professional facilities. In other words, the health service were not watching the doctors nor were they providing any benefits in the rural practice to make urban practice a less-rational choice.

Institutional constraints and individual rationality

An institution has different tools to guide and monitor its’ employees. These instruments are identified as institutional constraints in this paper. The policies, rules and regulations, supervising capability, monitoring system, institutional support etc. act as constraints of an institution. Institution plays a significant role in supervising the individuals, as Peters34 pointed out that ‘‘the mercurial and fickle nature of individual behaviour, and the need to direct that behaviour toward collective purposes, required forming political institution’’ (p.3). According to Sadiq,35 even if the doctors desire to work in rural areas, but they lose their interest because the health service fails to support them. If adequate institutional support were there, it would be possible to motivate the doctors to stay in the rural health facilities. According to Zey,36 ‘‘If individuals behave rationally, the collective will benefit; therefore, individuals should not be interfered with by the collective, except when individual behaviour undermines collective interests’’ (p.1). Therefore, individual rationality is also needed for social benefits. It is in the interest of the collective to allow individuals freedom to behave in ways that are rational for them. Only if individual behaviour is harmful to society does society have a right to interfere with the freedom of individuals to make rational choices.

Individual rationality

As shown in Table 1, most of the studies identified that less opportunity for private practice is one of the main reasons for the unwillingness of doctors to accept in addition to the lower quality of family life for urban families which have to live in a rural area. Some doctors’ spouses have jobs in the cities, or their children are studying in urban schools. So these doctors cannot shift their family to the posted village. They would have to live alone in the village and visit their urban families at weekends only. As a result of that painful option, they make their own choice to absent themselves from village duties. Some researchers identified unfamiliarity with rural life, an urban mindset which finds village people’s thinking too restrictive and conservative, negligence, and a perception that the village is not attractive to live in as reasons for doctors’ refusal to take up practice in rural areas. Essentially, strengthening the institutional constraints to limit doctors’ rational choice not to live in the villages means forcing the doctors to have a worse lifestyle in an unfamiliar, confining place.

State of institutional constraints in Bangladesh health sector

Lack of institutional support to maintain urban doctors’ quality of life in the villages

Almost each of the study identified lack of basic amenities and infrastructures, poor living conditions, fear for personal security, poor transportation, poor living condition, poor working condition as the sources of unwillingness. These factors highly affect doctors’ decision-making on whether or not to practice in villages.

Ineffectiveness of policy of institutional support for doctors in villages

The policy of the Government of Bangladesh intends to fill in the gap between urban and rural areas in the quality health services.5 Recent research8 has found that there is an imbalance in health resource distribution between rural and urban areas. They also found that Government have career development and promotion plans for health care workers in rural areas, including doctors, but these plans are often not clearly-drawn and not well-implemented.

Ineffective enforcement of rules

Baniamin and Jamil37 say that many developing countries have various governance-related challenges and regulatory limitations. According to them, ‘‘Opportunistic behaviour may become more prevalent where there are problematic governance and comparatively loose regulation’’ (p.1). It means that, if institutional constraints (i.e. governance and regulation) are weak, opportunistic behaviour will be stronger. This study found that rules are not enforced uniformly in developing countries. The doctors who have personal linkages with administrators in the health service get the postings they want.38 Thus, rural health facilities are not getting the best doctors: merely the least well-connected doctors who cannot get urban posting.

Lack of motivation for doctors to work in villages

There are so many reasons for a doctor to show interest in urban placement: the highest-income; the most-challenging practice using the latest technology to save lives; state-of-the-art housing; cultural and entertainment opportunities; the opportunity to teach or study at urban medical colleges; the best schools and social opportunities for his/her children; the best employment, study and social opportunities for his/her spouse; the best internet connections to keep abreast of latest medical developments and network around the world. What are the reasons for a doctor to serve in a village?: none of the above. Only village residents who regard the village as “home”, with personal and social networks there, or doctors with strong social commitment to live the life of the poor in order to cure the poor and give them a better life have any motivation at all to practice in the village. Liu and Mills39 point out that this is not just a matter of money: paying a rural loading to doctors who have nothing to spend the extra money on in the village, for example, may not create any motivation. The dilemma is that trying to recreate the benefits of urban life in the villages would simply be impossible.

Poor monitoring

It seems that health service monitoring of doctors’ activities at the rural level is very weak. Sadiq35 found that the local authority officials usually do not visit the health facilities regularly to see if the doctors are there. Most doctors in peripheral health centres may attend their centres as little as once or twice in a week - or even in a month. Thus, doctors get an open opportunity to be elsewhere than at their village postings.

The dilemma of financial incentives for suppliers of credence goods

Two people may act in different ways in the same situation based entirely on the types of incentives that are available to them at that time.40 Therefore, using incentives in the healthcare sector is also important. Baniamin and Jamil37 identified medical service as a ‘‘credence good’’. They showed how incentives affect opportunistic behaviour if institutional regulations are not strong enough. They stated that ‘‘The introduction of an incentive system for service providers may be problematic, as it may encourage service providers to act in opportunistic ways for the sake of personal gain. Opportunistic behaviour may become more prevalent where there are problematic governance and comparatively loose regulation’’ (p.1). This statement also supports the discussion in the previous paragraph from a theoretical perspective because of institutional weakness, individuals supplying credence goods may try to maximize their benefit by abusing the opportunity offered by the incentive.

DISCUSSION

The above findings indicate that there is an inverse proportional relationship between institutional constraints and individual rationality. If institutional constraints become stronger, individual rationality gets weaker and vice-versa. If the constraints are weak and ineffective, individual rationality prevails and individuals get the chance to maximize their utility. The innate conflict between these two, individual rationality and collective interest, as represented by the goals of social institutions, is not beneficial to society. Therefore, all public policy must represent a balance between individual rational choice and collective needs expressed by the regulations of social institutions. The balance can be moved, in favour of the individual or in favour of society but, in a democratic society which recognises both individual freedom and the need for State action in the collective interest, it can never be abolished or disregarded. In these terms, the issue in the rural placement of doctors is whether the balance now lies too far in favour of the doctors’ rational choice, so that the needs of village patients and the social interest in equal health care for all are not being met.

There are two policy options where the balance is not fair: force or incentives. Force means sacrificing the individuals’ interest in favour of the social interest by rigid control and punishment. In this case, it means making urban doctors’ families live like poor people or imprisoning the doctors in default. Incentives means transferring some social wealth to the individual so that the individual does not lose so much by taking the non-rational choice that benefits society. In this case, that means giving something to the doctors so that they can live more like the lives they lived in the city but now in the village. Incentives in this case, however, are fraught with complexities. They are not possible and they are open to abuse. The quality of life in the village can never be raised to the level of that available in the cities, only for doctors. Even financial incentives, the most popular kind, like exempting rural doctors’ income from tax or paying a subsidy to each doctor for each rural patient, would not work because what the doctors really crave in the city they cannot buy in the village even with infinite budgets. The published literature recognises that subsidising the producers of a credence good like medical services, in which the purchaser does not even understand whether proper service was rendered and no real competition is possible, opens great opportunities for abuse and the waste or theft of State funds with little benefit to the target group of rural patients.

Force is also not a serious option in this case. The theory of individual rational choice vs social institutional regulation seems to imply that, given strong enough institutional regulation, individual rational choice could simply be overwhelmed and crushed. Sato41 says that one of the main assumptions of the rational choice theory is that an actor chooses an alternative which maximizes his/her utility under subjectively conceived constraints and those constraints may make possible alternatives impossible. Kamel42 also came up with a similar idea that institutions have extensive influence on human behaviour through rules and norms. Yet this approach purports to abolish the balance between individual liberty and the social needs promoted by State institutions by simply ignoring it. The State which could achieve this total victory of social needs over individual rational choice would be, by definition, totalitarian and it would have to use totalitarian methods like force. Add in the reality, expressed in at least some of the published literature, that developing countries have weak systems of governance which tend to corruption and we see that these theories are talking not only about the horrible but also about the impossible. Using force to make doctors practice in rural areas in Bangladesh would probably not break the doctors’ will. In fact, it is already a law in Bangladesh that doctors must practice where they are posted and this is what has happened: where it could be enforced, doctors used money and personal connections to escape their legal duty.

So what is the way out of this conundrum? First, we must understand the problem properly. The problem of failure of supply of doctors in the rural areas is not a simple matter of bad, greedy doctors who need their heads broken open, after which all will be ideal in village health care. The problem goes to the roots of the insoluble conflict between the needs of society and the freedom of the individual and to the impossibility of providing equal resources to the poor and the rest of society in a developing country where all resources, including doctors, are not sufficient to meet everyone’s needs.

Understanding the complexity of the problem will keep us away from outrageous and unworkable “solutions”, like conscripting the doctors or handing buckets of money to rural doctors, that will not solve anything. We first need to realise that the problem probably cannot be solved, completely, in the short-term, until the rural and urban sectors in Bangladesh develop relatively equally. This realisation will allow us to focus on effective, incremental measures that may make the problem a little better. Probably the incremental measures that will work will come from the complex world of human psychology rather than the hard, dismal world of economics. As a study43 says, ‘‘doctors have adopted individual strategies to accommodate the advantages of both government employment and private practice in their career development, thus maximizing benefit from the incentives provided to them, e.g. status of a government job, and minimizing opportunity costs of economic losses e.g. lower salaries’’ (p.1). They are not so much “bad” as they are normal human beings trying to get the best of both worlds because neither one is enough to give them what they truly need.

According to Elster,44 ‘‘actions are explained by opportunities and desires- by what people can do and what they want to do’’ (p.14). If we want doctors to practice in the rural areas, we need to recruit doctors who like the rural areas, not expect urban doctors to exile themselves there. Indian doctors, as noted in this paper earlier, wanted to practice in the rural areas if they came from the rural areas. This is an important pointer to ameliorating the shortage of rural doctors. One obvious measure would be a crash programme of training rural medical students. For example, the State could commit to having at least one quality medical college in each of Bangladesh’s 64 Districts. Education there should be free for District residents who want to become doctors, on condition that they serve in their home districts, in their village of birth, for 20 years. To finance this scheme and to create the right incentives to get the social benefit desired, a 50% income tax surcharge could be imposed on urban medical practitioners. No doctor would be forced to reduce their standard of living to that in the village but, if they chose to practice in an oversupplied area for a much larger income, they would have to pay the social cost of that choice through the tax system. That is how economic incentives are intended to work. Perhaps this policy could be supported by privatising the medical colleges in urban areas, so urban medical students have to pay the full economic cost of urban medical education, to reduce the oversupply.

CONCLUSIONS

The study found that the problem of shortage of doctors in rural areas derives not only from doctors’ utility-maximizing behaviour but also from lack of institutional support. Institutional weakness creates opportunity for doctors to maximize their benefits. This research may have a far reaching impact on future studies. The theoretical framework this research proposed can be validated by empirical findings. The choice of urban doctors to practice in the cities is a perfectly-rational decision to get themselves and their families what they really need. We, too, in their position, would do the same. However, When these doctors make the most rational choice for themselves and their families, there are not enough doctors who want to serve in the rural areas where the majority of patients are. There is no solution to this social problem because we cannot (nor should we want to) force urban doctors to practice without motivation in isolated areas and incentives cannot work with a credence good like medical services. So our proposal is to reverse the implicit incentives in the current medical education and tax policy in Bangladesh to promote medical education for rural people and discourage medical educationand urban medical practice for urban people. The components of this policy would be: (a) a crash programme of building rural medical colleges to provide one in every District by 2025, offering free medical education to graduates who agree to practice in rural areas for 20 years (b) privatise urban medical colleges with no subsidies (c) impose a 50% income tax surcharge on medical practitioners in urban areas. Such a proposal is incremental, would not be opposed by anyone except urban medical practitioners who want to continue to externalize the social cost of their decision to practice in the city and would, over time, make a significant contribution toward equalising income and opportunity in medical services in Bangladesh.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the Public Policy and Governance Program of North South University, Bangladesh for the support that made this research possible. We thank South Asian Institute of Policy and Governance team including Professor Salahuddin M. Aminuzzaman, Professor Ishtiaq Jamil, Professor Sk. Tawfique M. Haque and Dr. Rizwan Khair. Special thanks to Dr. M. Mahfuzul Haque for sharing his ideas and field level experiences which enriched this paper. We also thank Dr. Jack Edward Effron for his valuable support in editing.

Funding: None.

Authorship contributions: AS and SA conceptualized the study. AS wrote the initial draft and SA provided critical comments. All authors edited the draft and approved the final manuscript to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Competing interests: The authors completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available upon request from the corresponding author), and declare no conflicts of interest.

Correspondence to:

Abdullah Shibli Sadiq,

Information Officer,

Press Information Department,

Ministry of Information,

Bangladesh Secretariat, Dhaka, Bangladesh

[email protected]