The Pacific region, also known as Oceania, is populated by people of diverse cultures and ethnicities. Pacific peoples are significantly affected by poor health including issues with nutrition, obesity, smoking and related diseases such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.1 Knowing how Pacific peoples perceive health and health services may help to understand the determinants of wellbeing and suggest ways for health services to support these populations. This study examined the health beliefs and behaviours of men from the island nation of Niue. This is an exploratory, qualitative study of a population that has poorly examined health-related beliefs and behaviours.

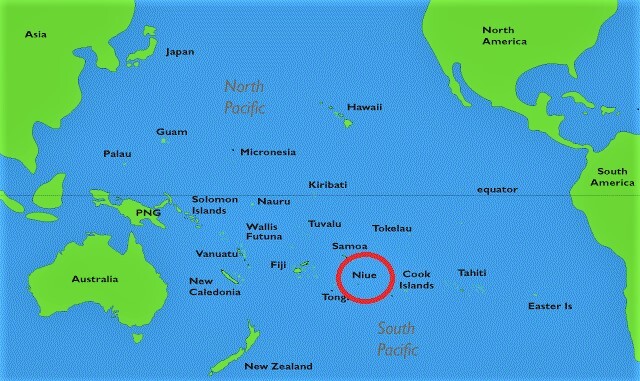

Niue is a small single island in the Pacific Ocean with a population of 1,719 people (831 men and 881 women). It is located in the South Pacific (lat. 169º55’W, long. 19º02’S), 2400km north east of New Zealand, 480km east of Tonga and 660km south east of Western Samoa (see Figure 1).2 It is 259 square kilometers in size (approximately 21 km by 18 km) and is the highest raised coral island in the world. The island is made up of 14 villages. The median age of the population is 33 years and the average household size is 3.3 people.3

The warm climate and low population has many benefits, but like other small island nations, Niue has a number of economic, social and health issues. These include geographical isolation, natural disasters, land tenure issues, poor infrastructure, low tourism numbers, low export of products and dependence on foreign aid.4 There is substantial migration to New Zealand as Niue is self-governed in association with New Zealand and all Niuean people are New Zealand citizens.5

Niue also has areas of innovation and as early as 2003 Niue was the first country in the world to offer all residents free Wi-Fi. About 7000 tourists visit each year.

Niue has free primary and secondary healthcare, all provided by a hospital health care provider. There are about 54 health care workers in the country. Health programmes include maternal and child health, obstetrics, medical and minor surgeries, public health, dental services, annual school health check-ups, health promotion and education and non-communicable disease action plans. People with complicated health issues are sent to New Zealand for medical care. The total expenditure on health as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) is 7.5%.5,6

Non communicable diseases are the most common health issue in Niue. In a recent WHO survey, about 16% of men and 8% of women said they smoked daily. Half of the population said they drank alcohol and of these 55% of men and 31% of women reported binge drinking at least once in the past month. Over 90% of the population reported consuming less than five serves of fruit and vegetables per day. Sixty one percent were obese (BMI ≥30kg/m2) and the average waist circumference was high at 98.9cm for men and 96.6cm for women. About one third of the population had high blood pressure (33%) and a similar proportion had raised blood sugar levels (38%) and raised cholesterol (34%). More men had poor health indicators than women.7

Little is known about whether people in Niue know what constitutes healthy and unhealthy behaviours and what influences their use of health services. This study sought to test the feasibility of asking men in Niue about these sensitive topics. Men were chosen because in Niue they are more likely to drink alcohol, smoke and be at high risk of cardiovascular disease than women, but are less likely to use available health services. The study did not aim to generalise the findings to the entire population, but rather to test whether men would agree to discuss their health behaviours and to identify trends that could be further researched.

METHODS

Ethical approval was provided by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee.

Data were collected from a convenience sample of 20 men living in villages throughout Niue. Men were eligible to take part if they were over the age of 16 years and living in Niue. Table 1 lists the characteristics of the participants, showing that there was a good mix of age ranges, education levels and other characteristics.

The researchers asked Niue’s Ministry of Health public health team to make local men aware of the interviews and we also contacted other community stakeholders to inform men by word of mouth. If men were interested in participating, they were asked to contact the researchers directly. When men contacted the researchers, an interview was scheduled with a view to gaining a good spread of geographic location and demographic characteristics.

We stopped recruiting after 20 participants because experience suggested that this was enough to gain saturation of themes and it worked well for our planned inductive analysis method.8 If the purpose of this research was to be able to generalise across the population we would have considered a larger sample and not relied on self-selection, but this was a feasibility study to understand whether men would be willing to participate, whether it was appropriate to undertake interviews in English and what themes might emerge for onward exploration. Twenty was enough to achieve those aims.

Face-to-face interviews were undertaken in English using a semi-structured interview schedule. Interview topics included health beliefs and practices and knowledge of healthcare services. The interviews took place in men’s homes, community venues or other venues that the participant nominated. One researcher undertook all the interviews for consistency. The interviewer spent time building rapport before formally beginning the interview. With participants’ consent, each interview was audio recorded and transcribed. The interview guide was tested before beginning the study and we reviewed the transcripts of initial interviews to validate the approach and questions. A NZ$50 dollar cash incentive was provided after the completion of the interviews to the participants to acknowledge for their time in participating in this research.

A general inductive approach was used to analyse the interview data. The aim of this approach is to allow findings to emerge from frequent or dominant themes inherent in the data.7 Each transcript was read systematically and multiple times by the authors to identify and code consistent themes. Two authors independently extracted themes and counted the number of occurrences. A third researcher cross checked the themes and aligned them to our research aims. Illustrative quotes were drawn out as examples to showcase the richness of the responses.

RESULTS

Face to face interviews were a feasible and informative approach to ask men in Niue about their health and health care. The men interviewed spoke openly and provided insights about factors that helped and hindered their health and the potential determinants of health.

The men interviewed had a reasonable understanding of healthy and unhealthy behaviours, but they did not always prioritise healthy behaviours. They were reluctant to visit health services when they had a health issue, seeing this as an unmasculine thing to do or saying that they were too stubborn or proud to seek help. Table 2 shows how many men mentioned various interview themes. This acts as a framework to present the results and to consider further research needs.

Understanding of healthy and unhealthy behaviours

Previous research has found that men in Niue smoke, drink and are more overweight than women in Niue and compared to populations in countries such as New Zealand, Australia and the US.8 It could be hypothesised that this is because men in Niue have limited knowledge of what constitutes healthy and unhealthy behaviours, but our interviews do not support this.

Instead, the men we interviewed were aware of healthy and unhealthy activities and they believed that healthy behaviours benefitted their wellbeing (90%).

Interviewees defined heath largely in terms of consuming fruit, vegetables and fish, being active, including working on their plantations and fishing, and avoiding unhealthy food, smoking and alcohol. They equated health with being happy, enjoying life and a positive mental outlook.

“Health is about being active, going to the bush and work, even with going to the sea, you have to work and do active stuff…For me, I think for Niueans we’re doing good and living a healthy life… (our problem is) it’s mainly our food intake and what we eat every day.”

The men interviewed were aware that non-communicable diseases were a burden in Niue. They suggested that eating ‘unhealthy foods’ imported from other countries and the way men eat was a cause of ill health, including obesity, diabetes, gout, high blood pressure and high cholesterol (85%).

“High blood pressure, and high cholesterol is because of the eating style and how you eat… It’s like no food in the morning and no lunch and then a heavy meal in the evening. And it’s a real problem because it’s very hard to change now because we still tend to follow that way…the food coming in from New Zealand and Australia are no good…they’re full of chemicals.”

The men also identified heavy drinking as an issue and believed that this was influenced by the ease of access to alcohol, peer pressure and a sense of it being ‘normal’ to drink at social occasions such as sporting events and family celebrations. Some participants reported that excessive alcohol consumption is more of an issue for younger rather than older men.

“I reckon drinking is a problem for the Niuean men, especially the younger ones. It’s that thing when you get older you already know what it’s like…I use to drink a lot when I was younger. It was a problem before but now with my family, it’s come down…We used to drink to socialise and because of peer pressure.”

Knowledge of health services

The men had high levels of knowledge about the health services available in Niue (100%), particularly men who had frequently used healthcare services in the past or who had family members employed in healthcare.

Amongst those interviewed, older men were more likely to have used or be using health services than younger men. Older men were also more likely get regular health check-ups.

Most men said they thought the quality of available health services was good, particularly as the services are free for people to use (85%). However, a smaller proportion (15%) said that certain healthcare services did not meet their expectations or needs. This was especially true for the after-hours healthcare service.

“After-hours, pretty low to be honest. Especially when we take our kids and we have to wait for the doctors for an hour or two. Or they will tell us to come back during working hours because the doctors not available.”

Reasons for not using health services

The interviewees said that men in Niue often did not visit health professionals when they were unwell and ‘held out’ until their ailments significantly worsened. The men said that they themselves would avoid using health services if they had a health issue (80%). They said this was due to their sense of pride and stubbornness. This may be due to a masculine culture where men do not want to admit that something may be wrong or that they cannot ‘fix’ an issue themselves.

“Pride! Pride! That would be the biggest one. They find themselves that they don’t need to see a doctor. They can fix it themselves. They can’t find themselves sharing with other men what’s wrong with them. Niuean men think that we are the only ones who can fix what we got.”

The men said that they and other men in their community did not want to worry or burden others with any illness they may have. They may also be concerned about the confidentiality of their information in a small community.

“I’ve known some people who don’t want to let people know that they have a health problem or that they are sick. Family and friends will always have to find out the hard way later on…most likely they don’t want to worry other people. They just want to keep it to themselves and not be other people’s problem…they’d rather keep it to themselves.”

Family played a significant role in influencing participants to see a doctor, especially if a family member worked in health services.

“Yes, especially my wife. She’s a nurse and she’s always trying to get me to go to the doctors.”

The characteristics of available health services did not appear to influence whether or not men used them. Men generally believed that healthcare services were of good quality and did not think that the ethnicity of doctors mattered, although if a choice was available, a Niue doctor would be preferred over doctors from other countries. This was stated as due to being able to more clearly communicate with a healthcare professional in the Niuean language.

“I found some of the doctors because it’s multicultural healthcare in the hospitals and we have doctors from different countries but I find that Niuean doctors are helpful because you can speak Niuean as well as English and you can tell a Niuean doctor exactly what is wrong. Because if you try to tell the same thing to a doctor from another country, even though they are qualified, you don’t seem to get the right answer back.”

Many of the older men interviewed said they used Niue traditional medicines when they were sick or injured in preference to visiting health services.

“I’ve learnt quite a bit of the basics about it from the older people and that it can help with the coughing and headaches…If I’m coughing then I usually use wild ginger and some of the bark from the trees and stuff like that.”

Ways to engage men in health and wellbeing

Although the men interviewed said there was reluctance amongst Niuean men to visit health services or be a ‘burden’, participants were eager to see more opportunities for men to get involved in health and wellbeing activities in their local communities.

A recurring suggestion from interviewees was to have wellbeing workshops or an exercise programme specifically for men in villages (85%). It was stated that such health promotion activities could provide men with information about health issues common to Niue men in a way that was entertaining and interactive.

Although there was much positivity about this approach from participants, they believed it may be a challenge to encourage men to participate in such programmes unless they were made fun and part of a communal approach.

“But even if a workshop is called…will they turn up? The best part of the workshop would be to individually go to each village instead of calling a major workshop, but take it to the village. And take it at a time where people are already gathered like after church. When there is a crowd. When the village is all there. It’s the best time to take workshops to them.”

Older men liked the idea of community health promotion workshops and the younger men interviewed were keen to see exercise programmes. Interviewees said that young men were interested in sport and competition and this could be used as a lever to engage them.

“Just try and make them compete with each other, something to keep them motivated, something to inspire them, like something that they think is fun but a bit of fitness as well. Yeah, do something that gets them in a healthy shape because if you try pushing them to do something, they won’t do it.”

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that it is feasible and worthwhile to engage with men one to one in seeking to understand how to help small communities and health services tackle health promotion. Interviews can provide a wealth of information about why men may not use health services or how they could be better engaged to tackle poor health outcomes. Men were willing to participate, including in English, and spoke openly about their beliefs and challenges.

Other researchers have found that men are less likely than women to visit health services when they are ill.9 Our interviews suggest that this is also the case in Niue and that this may be linked in part to notions of masculinity and not wanting to be a burden on others. To address this imbalance, work is needed to show men that it is a masculine trait to take care of themselves and remain able to provide for their family.

Our findings are similar to those in other Pacific nations, which found that health is equated with being happy.10 Linking health promotion to entertainment and other ‘happy’ activities could increase uptake of education or exercise programmes seeking to engage men who may otherwise shy away from health services. Working with local men to design health promotion programmes that are culturally appropriate may help to reduce the stigma attached to using health services or living with health conditions.

Our interviewees suggested that much ill health in Niue is related to unhealthy diets. Past research suggests that buying imported food products is more convenient than growing traditional food crops in Niue.11 This may mean that strategies to encourage families to maintain traditional crop growing practices could be an important public health initiative, alongside government taxation of imported food.

Excessive alcohol consumption is a health concern in Niue. It is concerning that interviewees suggested that alcohol has become part of the culture in Niue and is expected at sports events and family celebrations. Other researchers have also found that alcohol is an integral part of Niuean cultural rituals, provided as fakalofa (gifts) to signify generosity, as payment for work completed by family and friends and to reinforce communal cultural identity.12 Our study joins with others in suggesting that alcohol awareness programmes need to be developed that are culturally appropriate to the Niue context and which seek to show that alcohol need not be part of Niuean cultural hosting obligations.

Another implication of this research is the importance of developing more health professionals able to communicate in the Niuean language. Our interviewees felt more able to openly communicate their health issues with professionals who spoke in Niuean. This replicates the findings of other Pacific researchers.13,14

Limitations

This feasibility study has a number of limitations. We interviewed a small number of men, we focused on men only and we used a convenience sample that was self-selecting. We did not seek to represent the whole of the Niue population or all men in Niue. Themes were based on one interview with each man and we did not cross check men’s perceptions with others in their families or communities.

Interviewing as a method can introduce a range of biases, including selection bias and social desirability bias whereby the participants say what they think the interviewer wants to hear or what they feel is socially or culturally acceptable. We took steps to avoid this, by using an interviewer that was not known to the participants, using a semi-structured interview guide, sensitively prompting men to explain their reasons and trying not to imply any judgement about answers. Even so, we recognise that the process of interviewing, as with all methods, may introduce biases and affect the type of information provided.

We conducted the interviews in English, which may have limited the interviewees’ level of comfort and ability to express themselves. We did not experience any issues being understood by the participants (teaching in Niue is undertaken in English) or in the interviewer or data analysts understanding the dialects of the participants. Our team included one researcher of Niuean descent and two from another Pacific background, so the language and cultural style was familiar to the researchers.

Despite the limitations we fulfilled our aim to examine the feasibility of speaking with men about sensitive topics related to health and wellbeing.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we have shown that men from Niue are interested in sharing their views about health and healthcare and further research could build on this willingness to participate. This small study suggests that there is much scope for research to consider whether men and women have similar health-related beliefs and behaviours in Niue, to explore what would encourage the population to use health services more proactively and to understand the most effective ways to promote health and wellbeing. Men in Niue die earlier than women on average2 so there is scope for research with both sexes to understand the difference in their lifestyle and disease burden.

It may be a priority to consider how to develop and prioritise community activities to encourage men to engage in a healthier lifestyle. These may include workshops, exercise classes, healthy eating demonstrations, sports and other activities designed to promote health in an engaging manner, challenge stereotypical notions of masculinity and alcohol use and recognise cultural issues. Offering activities in villages and targeting activities to particular age groups could be worthwhile.

With only a limited number of health professionals in Niue, it may be worthwhile to consider how volunteers or senior community members could be trained to support or deliver health promotion work, and this has the added benefit of coproduction and embedding in the community. Such activities at individual level could go hand in hand with government-level initiatives to consider taxation of imported foods and alcohol.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank all the Niue men who participated in this research, Niue government, Niue Ministry of Health, and the Niue Public Health team.

Funding: New Zealand Health Research Council Emerging First Grant.

Authorship contributions: VN & KF collected the data and wrote the first draft of the article. DdS assisted with the analysis and substantially revised the final draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Competing interests: The authors completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available upon request from the corresponding author), and declare no conflicts of interest.

Correspondence to:

Associate Professor Vili Nosa

Pacific Health Section, School of Population Health

Faculty of Medical & Health Science

The University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019

Auckland Mail Centre, Auckland 1142

[email protected]