Community engagement and empowerment are recognized as critical components of HIV programming, particularly for key population groups affected by HIV (men who have sex with men, transgender women, people who inject drugs, and sex workers.1–3 The World Health Organization defines community empowerment as “a collective process that enables key populations to address the structural constraints to health, human rights and well-being… and improve access to health services.”1 Members of key populations experience intersecting forms of stigma and have been historically excluded from public health services, underscoring the need for meaningful participation and community engagement and empowerment.1,4–7 Activities supporting community engagement and empowerment range from meaningful involvement in planning, budgeting, and execution of service delivery actions to service delivery led by key population communities and enhancement of such services through capacity development interventions.1,8 Forming community advisory boards, facilitating civil society organizations’ (CSOs) access to systems that have influence, and strengthening advocacy skills are also forms of community engagement and empowerment.9

While evidence is limited, interventions delivered through a community empowerment model have demonstrated positive HIV-related outcomes such as reduced HIV prevalence and increased condom use.8,10 Recognizing this, donors have moved to strengthen engagement with key population communities in program planning, implementation, and monitoring. The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) now requires community engagement prior to annual planning meetings,3,11,12 and the Global Fund established communication and coordination platforms as a mechanism for community engagement.13 As donors look to transition HIV programming to be financed and managed by host countries (country ownership), government engagement with communities and CSOs is considered a determinant of readiness.14

Through the USAID- and PEPFAR-supported Linkages across the Continuum of HIV Services for Key Populations Affected by HIV (LINKAGES) project, FHI 360 and partners Pact, IntraHealth International, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill work with more than 100 local partners to plan, deliver, and strengthen services to reduce HIV transmission among members of key populations and their partners and extend the lives of those already living with HIV. LINKAGES programming aims to be key population led and provide meaningful opportunities for the inclusion of key population perspectives regarding how services are delivered, improved, and evaluated. LINKAGES’ local CSO partners are selected through solicitation processes to identify who can provide high-quality services along the HIV continuum of care to key population communities. Selected CSOs receive subawards from FHI 360 with specific programming expectations, such as numerical targets of individuals to reach with prevention, testing, and treatment services. CSOs are given options for capacity development to reach goals through training, coaching, mentoring, participation in south-to-south mentoring and learning exchanges, and virtual support. Specific areas for technical assistance are identified collaboratively between CSOs and LINKAGES staff through assessments, participation in workshops, and exposure to new methods for programming, and may include both organizational development support and enhancement of technical implementation capacity.

This paper presents results from a survey of CSOs working with the LINKAGES project. Our goal was to document CSO perspectives on LINKAGES’ engagement of key population communities, the benefits and challenges of receiving U.S. government (USG) funding through LINKAGES, and perceptions of their own sustainability as a result of work with LINKAGES. The findings also provide insights related to preparing local CSOs for direct funding from donors and national governments in the larger policy context of country ownership.

METHODS

We conducted an online survey with CSOs to document CSO perspectives related to working as a local implementing partner for LINKAGES.

Recruitment

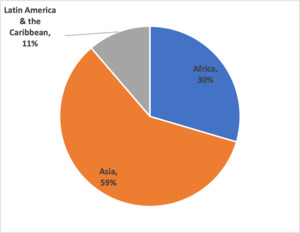

In March 2018, all CSOs implementing LINKAGES service delivery subawards for at least six months were invited to participate in the survey via email. In total, 116 CSOs operating in countries where LINKAGES supported programming (60 across Africa, 41 in Asia, and 15 across Latin America and the Caribbean [LAC]) received the survey and a reminder to participate. CSO staff were encouraged to submit one survey response per organization.

Implementation

The survey included closed- and open-ended questions and was administered using Qualtrics. The questions were designed by the research team, reviewed by LINKAGES leadership, and then field-tested with two CSOs in Thailand. The survey was available in French and English, and one office translated the survey into Bahasa Indonesia. All responses were translated into English for analysis.

Analysis

We used Microsoft Excel and SAS 9.4 to conduct descriptive analyses. We report percentages for categorical variables and the mean and standard deviation and median and range for continuous variables. Data from open-ended questions were analyzed using a data reduction matrix. The research team read all open-ended responses for clarity and corrected unclear segments, then categorized responses to each question using either discrete categories or short summaries and associated quotes. An inductive thematic analysis was then conducted using memo writing to answer the research questions.

RESULTS

We present findings in four sections: CSO perceptions of community engagement with LINKAGES; the benefits experienced by CSOs and the communities they serve through implementing LINKAGES programming; the challenges CSOs described in working with LINKAGES; and perceived sustainability of CSOs as a result of partnering with LINKAGES. Throughout the results, we also share suggestions provided by CSOs for increasing CSO engagement.

Sample

Responses were received from 71 CSOs across 18 countries (figure 1): Botswana, Burundi, Cote d’Ivoire, Haiti, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, Kenya, Laos, Malawi, Mali, Nepal, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Suriname, Swaziland, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago. More than half of respondents (59%) were from Asia, 30% from Africa, and 11% from LAC. Nearly half (42%) of the CSOs self-defined as key population led. On average, CSOs had been operating for 15.6 (SD 9.1) years with 43.4 (SD 82.8) full-time employees and 44 (SD 72.9) part-time employees (including volunteers). Of the respondents, 39% stated more than three-quarters of employees identify as members of key populations, 38% stated between one and three-quarters identify as such, and 23% stated less than one-quarter of employees do. Table 1 presents additional characteristics of the sample.

Perceptions of community engagement under LINKAGES

Of responding CSOs, 76% reported that key population communities were engaged in the planning and implementation of LINKAGES activities, and another 13% stated that activities are often proposed and led by members of key populations. Respondents suggested several strategies to better involve key population communities in LINKAGES activities. The most common suggestion was to organize regular sessions with them to solicit feedback on LINKAGES activities. A majority of respondents also requested that key population communities be more meaningfully engaged in the design and planning process to strengthen overall program implementation. Ten (17%) respondents wanted greater involvement in the decision-making processes within program planning and implementation. Several CSOs noted that members of key populations are largely absent from the evaluation process, and one CSO suggested that LINKAGES “…actively involve [members of key populations] as evaluators” as opposed to participants.

As institutional trust is an important indicator of successful community engagement, we asked if the services provided through LINKAGES CSOs were trusted within the key population communities they serve. The majority (96%) of respondents indicated that this trust did exist. Trust was attributed to the high standards of privacy and confidentiality maintained by LINKAGES partners, the quality of services, the length of time CSOs had been working in the community, and the involvement of key population community opinion leaders in the program. To further improve institutional trust, respondents recommended involving more key population members in all stages of program planning, especially design.

Perceptions of the benefits of working with LINKAGES

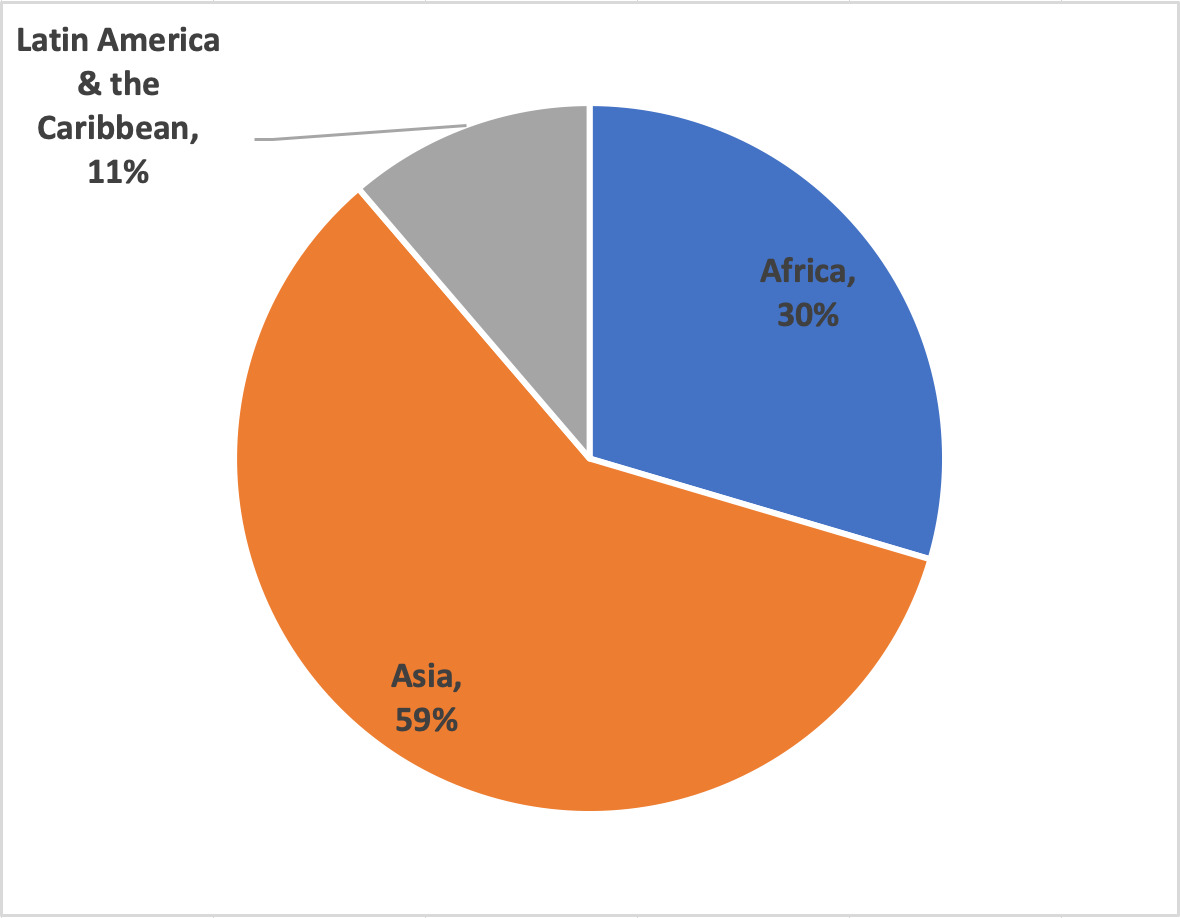

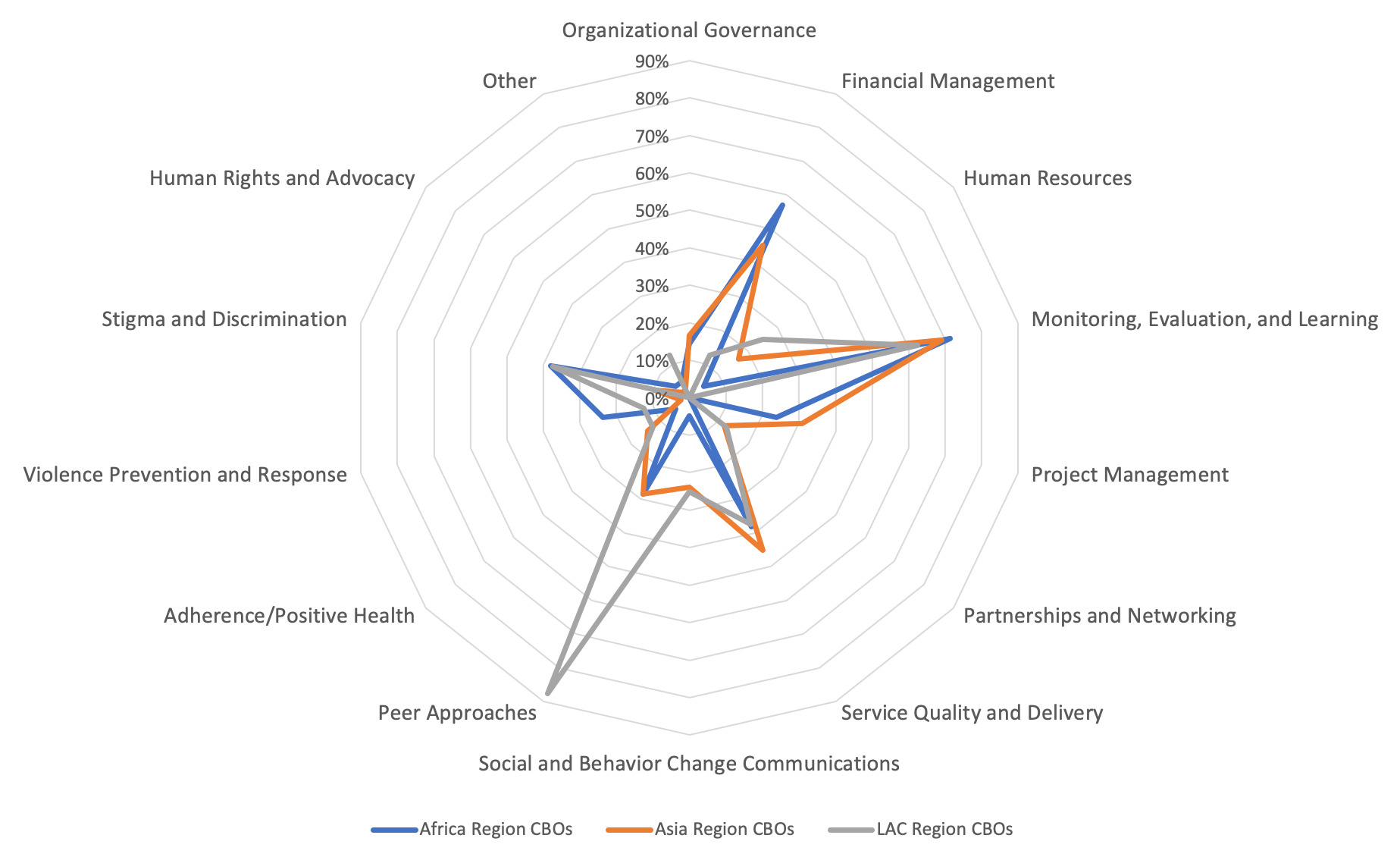

Globally, CSOs reported the three most-valued areas of support they received from LINKAGES were monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) (21%); financial management (14%); and service quality and delivery (13.5%) as shown in Figure 2. Additionally, CSOs identified technical assistance around implementing HIV programming for members of key populations and program management support as helpful. The areas of support valued varied by region. CSOs from Africa valued stigma and discrimination support as much as service quality and delivery. The majority of CSOs in the LAC region (88% [n=8]) valued receiving technical assistance on peer approaches for reaching members of key populations over other technical assistance areas (Figure 3). Self-described key-population-led organizations also valued peer approaches more than non-key-population-led CSOs, while 80% (n=30) of key-population-led organizations valued MEL assistance versus 59% of non-key-population-led CSOs.

CSOs were also asked to describe how LINKAGES could better assist CSOs in reaching their goals under LINKAGES. Responses included: additional capacity development support (defined as organizational development and technical programming enhancement), addressing funding constraints, and expanding work scopes.

Challenges associated with receiving U.S. government funding

While 87% of CSOs found the LINKAGES project “very helpful” in supporting their work with key population communities, they also reported a variety of challenges in working with USG funding through LINKAGES. Most challenges were related to program management and technical implementation. These included:

-

Contractual requirements including the volume of documentation required for USG funding, high program achievement targets, and the limitations on how funding can be spent. One CSO reported: “Too much administrative details and attention burdening our staff and affecting performance and program impact. Bulky paperwork and data tools take too much of our outreach team time hence they are poorly remunerated.”

-

Limited technical scope of LINKAGES inhibiting their ability to incorporate economic strengthening, and human rights and advocacy activities they deem priorities for their communities.

-

Funding constraints such as imbalance between the level of funding and the scope of work, delayed payments, concerns about future funding, and issues with consistency of funding. One CSO described the main challenges as “1. Low budget, 2. High targets and low human resources.”

-

Human resource constraints including staff turnover, lack of human resources to reach targets, limited pay for staff, and staff lacking the necessary skill sets.

CSOs also mentioned other challenges common to implementing programs for key population communities including difficulties engaging and retaining clients along the continuum of HIV care due to systemic and structural issues. Almost 30% of respondents reported difficulty accessing and engaging key population communities due to challenges such as the mobile nature of these groups, the legal environment including the criminalization of some key population behaviors, and political instability.

When further analyzed by type of CSO, non-key-population-led CSOs reported funding constraints, such as discrepancy between the amount of their subaward and the scope of their work, as the most prominent challenge. For key-population-led CSOs, contractual requirements were found to be the greatest challenge. Additional differences by region are described in figure 4.

Perceptions of sustainability under LINKAGES

Sustainability refers to an organization’s ability to continually achieve goals over time.15 Respondents stated that their CSO financial, organizational, technical, and structural sustainability had increased somewhat (51%) or substantially (33%) as a result of partnering with LINKAGES (n=69).

“It [LINKAGES] has enabled us get noticed and linked up with organizations that are supporting our sustainability plans. The strengthening of our monitoring, reporting, and financial systems gives confidence to prospective donors who are always impressed with the systems we have as a local organization. We envisage to still gain more from LINKAGES through their support. We are not yet at a level that we can say we are sustainable, but we are now on the right path and with more input we see ourselves getting to the highest sustainable level.”

Nineteen CSOs (32%) attributed stronger financial and management systems to their increased sustainability, including improving their ability to pay staff on time and having more supportive oversight systems. As a CSO noted, “Technical assistance from LINKAGES does not guarantee sustainability; however, it helps to ensure that we have sufficient internal structures and policies aligning with international standards [which]…make us more…[likely] to receive future funding from other donors.” Twelve CSOs attributed the increase in sustainability to the strengthening of staff technical skills, and some attributed it to expanded geographical coverage due to LINKAGES funding and stronger relationships with other partners. Of the four CSOs that reported a perceived decrease in sustainability, all attributed this to the restrictive nature of LINKAGES funding to support only specific activities.

As an indicator of increased financial sustainability, CSOs were asked whether they had received additional donor funding to continue or expand programming for key population communities since beginning work with LINKAGES. Nearly half (46%) reported they had received additional funding.

DISCUSSION

We found a majority of local CSO partners felt engaged in the planning and implementation of the LINKAGES project. CSOs provided suggestions for greater involvement including regular sessions with key population communities to solicit feedback, more involvement in program decision-making, and involvement of key population members in program evaluation. While trust in LINKAGES was high, CSOs indicated that additional community engagement in all stages of program planning would further strengthen that trust.

LINKAGES partners overwhelmingly found capacity development, specifically technical assistance with MEL, financial management, and HIV service quality and delivery support, to be helpful in implementing programming. Human rights, advocacy, and violence prevention assistance were not as highly valued; however, this may not necessarily be due to lesser importance. CSOs may have already had these skills, these areas of work may not have been the focus of the specific LINKAGES programming in country and thus technical assistance was outside the scope of that program in country, the assistance may not have been requested or offered as a possibility, or other priorities may have been higher related to compliance with subaward requirements. Additionally, how CSOs valued assistance varied by region. For example, CSOs in Africa valued stigma and discrimination support over other areas. This may be due to the greater structural stigma and reduced social acceptance for men who have sex with men and transgender women in Africa compared to other regions.16,17 CSOs in the LAC region valued technical assistance on peer approaches for reaching members of key populations, which may be related to the CSOs’ work objectives in the region compared to other regions. These differences highlight the importance of contextualizing and adapting global programming and capacity development support to the local needs of each CSO.

The most valued types of support also align with the most common challenges reported by CSOs. LINKAGES-supported CSOs found meeting targets, contractual requirements, and limited financial resources to be some of their greatest challenges. More specifically, the volume of documentation required to report on USG-funded programming was repeatedly described as a burden. The noted challenges also speak to well-known concerns of local partners about managing and implementing with direct funding from the USG18 beyond the LINKAGES project. Partner concerns about meeting ambitious PEPFAR targets, complying with USG regulations and program reporting requirements, and burdensome and frequent financial reporting while also reaching people vulnerable to HIV will need to be addressed and mitigated as more local partners are directly funded by the USG to achieve and maintain epidemic control. While capacity development support has helped mitigate some of these concerns, additional support is still needed.

LINKAGES CSOs pointed to structural barriers including migration, prohibitive policies, and legal barriers as impacting their ability to engage members of key populations along the HIV continuum of care. CSOs spoke to challenges addressing structural barriers given the limited scope of LINKAGES’ subawards, which require them to focus on reaching service delivery targets and have limited flexibility to support economic strengthening interventions, address human rights violations, or conduct policy advocacy activities. Together, these findings speak to the need for USG and local government funding to support evidence-based measures to reduce structural barriers for key population communities as part of a holistic approach to improve HIV outcomes globally.

As funders push for greater host-country-financed HIV epidemic control, for example, through initiatives such as PEPFAR Local Partner targets19 and USAID’s Journey to Self-Reliance20 critical considerations include: how to better involve key population communities, capacity development needs, and local CSO perspectives on community engagement. Previous efforts to shift funding to local partners have underscored the need to work with local CSOs to strengthen financial capacity and accountability systems,14,21 and ensure technical and programmatic readiness to receive direct funding.22 They have also demonstrated the need for local governments to engage appropriate stakeholders, allow adequate time for meaningful engagement of CSOs,14 handover service delivery from donor to local government23 carefully, and ascertain willingness of local governments to ensure nondiscriminatory access to HIV services.24

While transitioning services to local ownership in countries will be challenging, ensuring that key population communities continue to be engaged in planning and implementing HIV services is critically necessary,14 particularly in locations where country ownership may lead to decreased access to services.4,14 Our survey results reinforce the importance of continued, deliberate local partner engagement and empowerment—specifically those led by and/or serving key population communities—to ensure programming meets the needs of communities, reaches those most in need, and can be sustained by local partners.

Our study had some limitations. First, the survey was not available in all local languages and not all CSOs had the capacity to reply in the languages in which the survey was available. Our sample does not reflect all CSOs or countries where LINKAGES works—71 of 116 CSOs responded, and 18 of 23 countries were represented. As the number of CSOs LINKAGES works with varies by region, regions are not equally represented. Also, CSOs operating under LINKAGES varied in size, which may have had an impact on their responses to survey questions. Additionally, these findings may be reflective of more well-established CSOs, particularly in Asia where CSOs were nearly five years older, on average, than those in Africa and 10 years older than those in LAC. Our results, therefore, may not reflect the perceptions of younger CSOs that may have different experiences. Differences in responses by region, as well as by KP-led or non-KP-led CSOs, are provided for selected questions to capture regional differences. Limited responses from LAC may be attributed to the limited number of CSOs working with LINKAGES in the region. Therefore, responses are not representative of all CSOs receiving subawards to deliver HIV services through LINKAGES.

CONCLUSIONS

USG-funded CSOs working to improve HIV care and treatment outcomes among key population communities in 18 countries as part of the LINKAGES project reported they have been meaningfully involved in the program and found LINKAGES to be very helpful in their work. Nevertheless, they still desired greater engagement with members of key populations, especially in decision-making and evaluation of HIV programming. They highly valued capacity strengthening provided by LINKAGES, specifically related to monitoring and evaluation, financial management, and HIV service quality and delivery. The vast majority believed the project has contributed to increased sustainability of their organization.

Primary challenges of implementing LINKAGES programming included meeting targets, financial constraints, and reporting requirements, as well as limited support to address structural barriers to engaging key populations in services. Effective HIV programming with key populations necessitates engaging them in every aspect of project planning, implementation, and assessment, and strengthening investments to address the many structural barriers that exist for these communities. Community engagement and empowerment, including through ongoing local capacity development efforts, are also critical to sustain a locally led response to the HIV epidemic and to ensure directly funded local partners can be successful.

Ethics: The study was reviewed and approved by the FHI 360 Protection of Human Subjects Committee.

Funding: This publication was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the LINKAGES project, cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-14-00045. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, PEPFAR, or the United States Government.

Authorship contributions: AM: Research design and collection, data analysis, writing. DD: Research design and collection, data analysis, writing. EE: Research design and collection, data analysis, writing. BW: Research design and collection, writing. RW: Data analysis, writing

Competing interests: The authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available upon request from the corresponding author) and declare no conflicts of interest.

Corresponding author:

Amita Mehrotra, MPH

359 Blackwell Street Suite 200

Durham, North Carolina 27701

[email protected]