Oxygen is critical to the prevention of hypoxemia-induced morbidity and mortality.1 The World Health Organization estimates that 20-40% of the estimated 800,000 global pneumonia-related deaths annually could be prevented with the availability of oxygen.2 Yet, access to this life-saving treatment remains inadequate in most low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) despite billions of dollars spent to increase supply plants, infrastructure, and conserving devices.3–7 The critical shortage of oxygen has been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, exposing inadequacies in the oxygen delivery infrastructure even in high-income countries and identifying the need to retrofit hospital equipment to adequately deal with future pandemics.8

Oxygen-conserving devices attempt to reduce the oxygen wasted during the exhalation phase of the respiratory cycle, thereby extending the current supply of medical oxygen.9 Such devices include reservoir cannulas, transtracheal catheters, and pulse demand oxygen delivery devices that connect to oxygen tanks or concentrators.9 However, currently available conserving devices continue to face a trade-off between efficiency (oxygen savings) and effectiveness (maintaining peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2)). Reservoir cannulas produce the best oxygen savings at lower doses (e.g., 1-2 liters per minute (L/min)) with a drop-off in savings as dose demands increase.10 Research on pulse demand conservation devices’ performance in clinical patients remains limited, and our review of the literature found no studies evaluating their degree of savings across doses. Manufacturers’ oxygen savings data on websites and in manuals are most often described as a maximum achievable savings ratio or a table of the average savings ratios for each combination of the device’s setting (e.g., 1, 2, 3) across different respiratory rates (e.g., 15, 20, or 25 breaths per minute).11–16 However, this does not provide insight into the savings performance as a patient aims to achieve a target SpO2 throughout the day. Further, some conserving devices, such as portable oxygen concentrators, are not able to provide over 3 L/min dose equivalent at their highest settings of continuous flow output.17 This leaves patients who require higher doses with few options to achieve both their saturation needs and conservation of oxygen.18

In LMICs, a common solution to the oxygen supply crisis has been the use of oxygen concentrators. While these can overcome issues of oxygen cylinder supply chain and delivery obstacles, concentrators bring other challenges. For example, there is a high up-front cost to purchase the device, ongoing electricity requirements of 100-600 watts per hour, heat and noise, regular filter changes and other supplies, and the need for trained personnel to repair and maintain equipment.19 Many LMICs also face electricity instability, rendering concentrators unusable for minutes to days at a time.20–22 The implementation of concentrators as the main oxygen supply has necessitated solutions for power stability such as power generators and solar technology solutions.23,24 The feasibility and cost-effectiveness studies have been positive, while there remain barriers including the initial investment and infrastructure required to launch community-wide initiatives.23,25

As an alternative, we present a conservation method that delivers oxygen under ambient pressure. The OXFO System (OXFO Corp, Boston, MA, USA) is an approved class IIa device by the National Institute for Food and Drug Surveillance in Colombia (INVIMA). The primary aims of this study were to examine the oxygen volume savings and test the non-inferiority of mean SpO2 with the OXFO System compared to standard continuous flow delivery in a clinical population of hospitalized oxygen-dependent adults.

OXFO System Design

The OXFO System achieves the conservation of oxygen similarly to reservoir cannulas in that there is a reservoir chamber that is filled by a pressurized oxygen source and held in place until patient inhalation. Reservoir cannulas conserve by allowing a reduced rate of continuous flow to achieve the same fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) as continuous flow alone, and less oxygen is required to achieve the clinical goals. In the OXFO System, the reservoir has been made much larger and placed further away from the patient compared to a reservoir cannula. The reservoir in the OXFO System is large enough that no continuous flow is required to supplement the reservoir volume of oxygen during inhalation. Rather, only an intermittent flow is required to refill the reservoir.

A pressurized source of oxygen is received by this device where it is converted to and stored at ambient pressure in a flexible reservoir bag within the device. Oxygen remains available for the patient to withdraw with each unique breath at any time, frequency, velocity, and volume. As the patient inhales, the negative pressure opens a one-way valve and oxygen is withdrawn from the reservoir for the entirety of inspiration. No bolus is delivered because there is no pressurized force when the valve opens during inhalation. An analogy is to imagine currently available oxygen-conserving devices all operating under pressure as different nozzles or sprinklers attached to a hose connected to a water source. When one wants to take a drink of water, the valve is opened and releases the water at a set pressure and frequency. In contrast, the OXFO System is like a glass of water with a straw and one can suck through the straw exactly the amount and speed that one prefers at any interval.

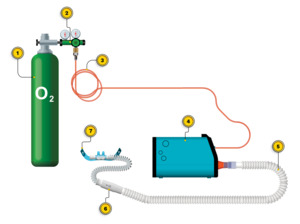

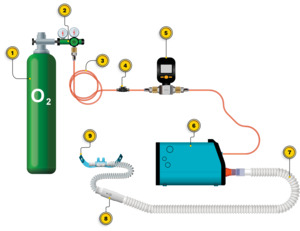

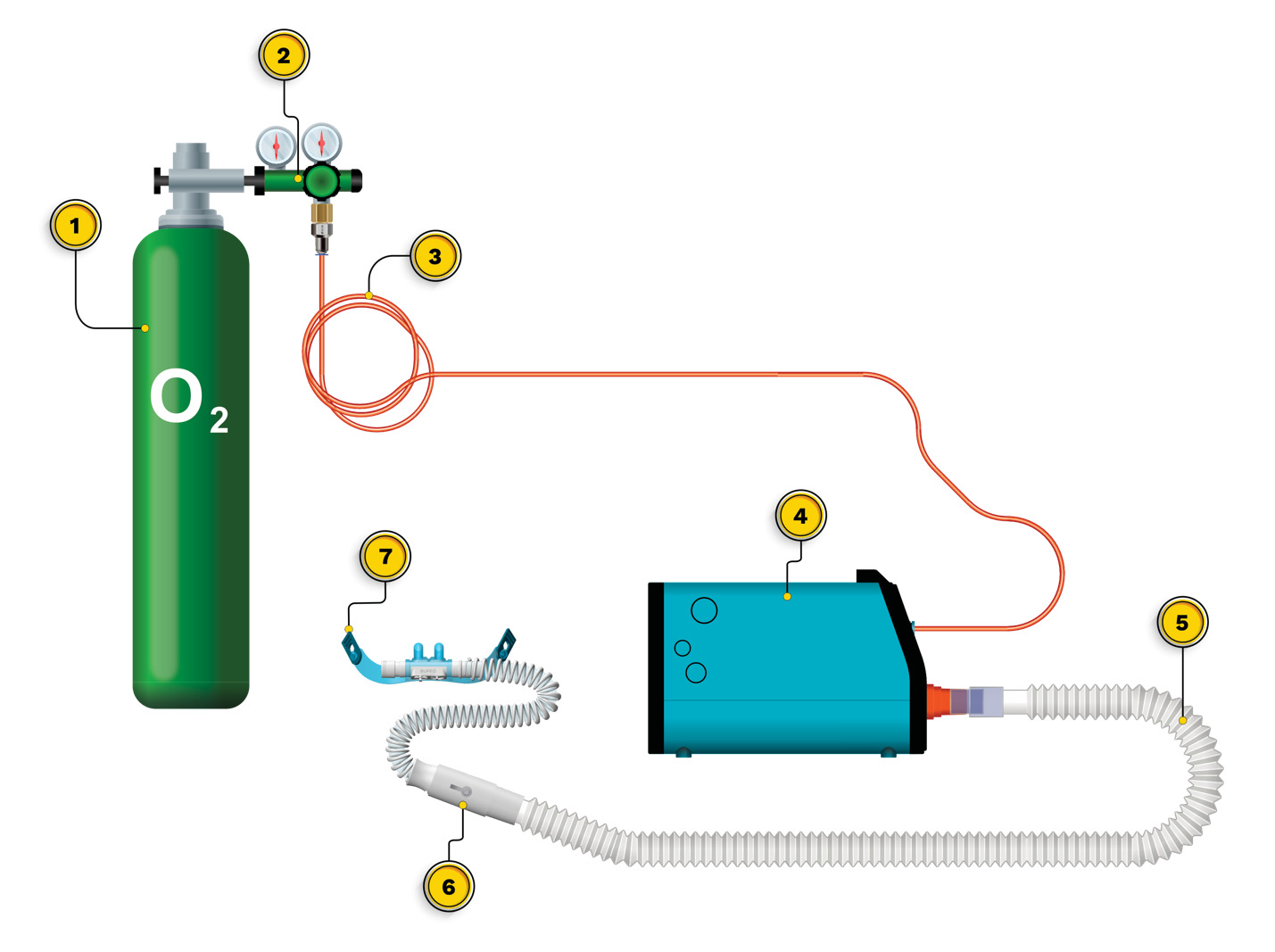

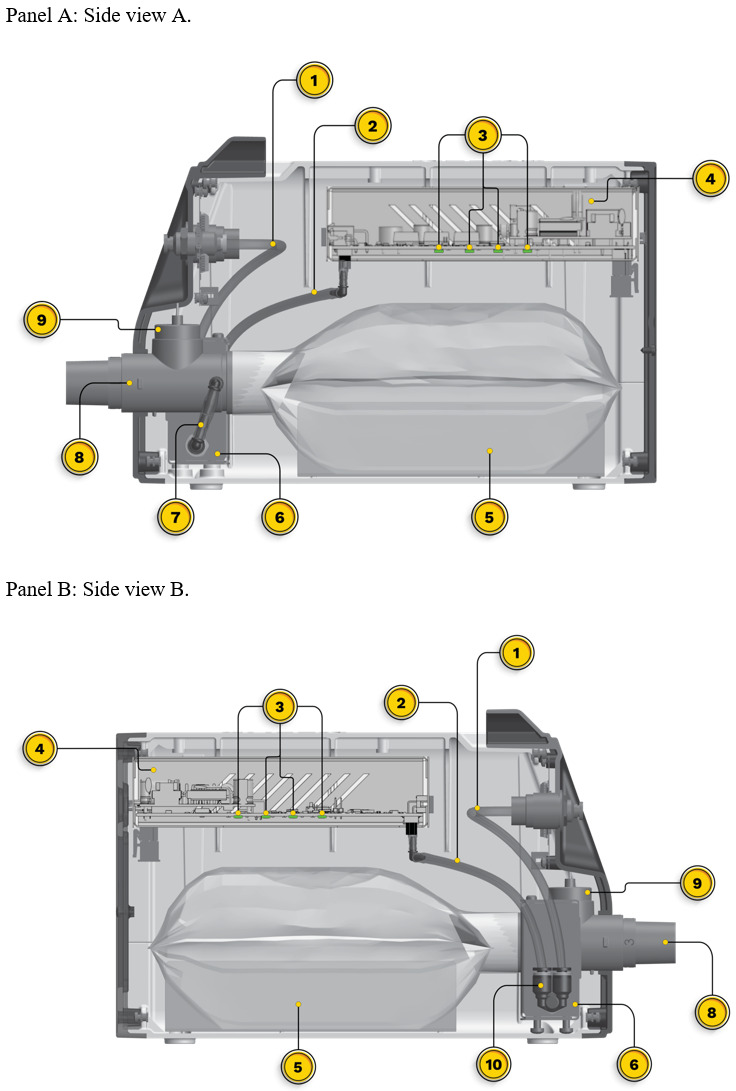

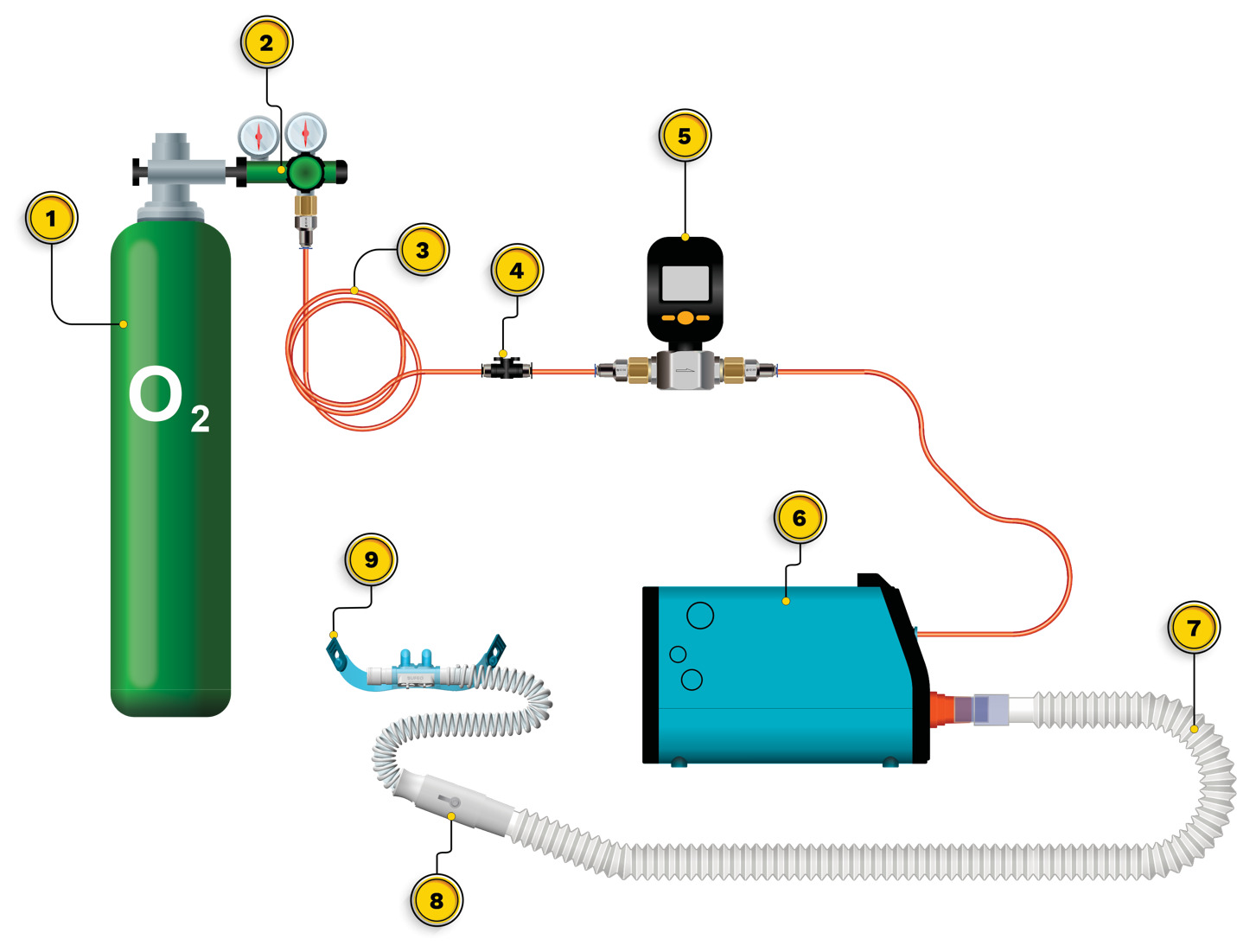

Initial setup of the OXFO System includes placing the device on a surface in proximity to the patient and connecting the output port to corrugated respiratory circuit tubing, then to a 1-way valve, and then to the mask or high-flow nasal cannula (Figure 1). The pressurized source is then connected to the front input port of the OXFO device (Figure 1; Figure 2). Then power is switched on and the system fills and purges oxygen to ensure that the corrugated tubing connecting to the mask or cannula is also filled with oxygen before use. The electronic pressure sensors (Figure 3) will detect if there is a pressurized source of oxygen connected or not and LED lights on the front (Figure 2) indicate green for adequate oxygen source or red if there is not. Internal tubing from the oxygen input port receives pressurized oxygen and connects to a Y-valve (Figure 3). One branch connects to a pressure sensor in the electronics casing (Figure 3) to determine if the lights and sounds need to alert the user to a lack of adequate oxygen.

The second branch of the oxygen input tubing to the Y-valve connects to the solenoid valve (Figure 3). Infrared sensors along the bottom of the electronics casing (Figure 3) measure the distance between them and the reservoir bag and signal the opening or closing of the solenoid valve to fill the reservoir. Upon opening, oxygen is passed through the solenoid valve to a channel directing oxygen into the reservoir bag where the oxygen disperses at ambient pressure (Figure 3). When the average distance among the infrared sensors is 1 cm, the solenoid valve closes. As the patient breathes and the reservoir bag lowers with each breath, the sensors open the solenoid valve when they measure the average distance to be 7 cm. When filled, the oxygen at ambient pressure remains in place awaiting withdrawal by the patient during inspiration. In the water analogy, when the water level in the glass is at a low point, but not empty, the faucet is turned on to refill the glass and shuts off when the glass is full, with no spillover or waste.

The user can titrate OXFO to meet the patient’s SpO2 requirements through 2 mechanisms. The selection of a facemask or nasal cannula size and a blender along the output port (Figure 3) can both be adjusted to allow the necessary entrainment of room air with inhalation. This method uses a fixed ratio of oxygen to air rather than a fixed volume of oxygen so that as the patient’s tidal volume and respiratory frequency fluctuate, the volumes of both oxygen and entrained air also fluctuate in a constant ratio. The blender can be closed to room air, or adjusted to various open positions. Similarly, a well-sealed facemask would be closed to room air on inhalation or a smaller nasal cannula in proportion to the patient’s nares would allow more entrained air.

The OXFO System has an electricity requirement of 5 Watts per hour only while the reservoir refills, a weight of 1.5 kg, and a battery life of up to 12 hours. The software can be serviced remotely through wi-fi. The pressurized oxygen can come from any source at a setting of 15 L/min to 60 L/min, including directly from a standard hospital wall port.

METHODS

This study was reviewed and approved by the Hospital Alma Máter de Antioquia Research Ethics Committee and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05677009). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Subjects were recruited from one private hospital in Medellín, Colombia.

Subjects

Stable hospitalized patients aged 18-70 years and prescribed supplemental medical oxygen of a dose ≥2 L/min were invited to participate in this single-visit study. The eligibility criteria are described in Table 1.

Study Conditions

The OXFO System is an approved class IIa device by the National Institute for Food and Drug Surveillance in Colombia (INVIMA). The OXFO Condition apparatus is shown in Figure 4. The OXFO System was connected to a compressed cylinder as the oxygen source. Titration to target saturation involved the selection of a mask or one of three size cannulas, and/or adjustment of a blender at the output port with settings from 0 to 3 with 0 representing no entrained air, and 1-3 allowing entrained air with graded increases. The facemask in OXFO Condition was a mask with a silicone border that adjusts to the subject’s face for a complete seal, vents on each side, and an adjustable elastic band. The nasal cannula in OXFO Condition was a commercially available high-flow nasal cannula with adjustable elastic bands, and these came in a selection of 3 different sizes (small, medium, and large nasal prong diameters).

The Standard Condition was the baseline apparatus utilized by the subject at the time of enrollment in the study, including the mask or cannula (Figure 5). A measurement of the prescribed hospital dose was made by attaching one of the study’s passive flowmeters in between the hospital regulator and the mask or cannula tubing. The flowmeter remained in place for measuring volume during Standard Condition. Titration of the continuous flow to target saturation involved adjusting the hospital regulator flow.

Study Activities

Eligible subjects were randomly assigned to receive either Standard Condition or OXFO Condition first, and then cross over to the other condition. In each condition, subjects were titrated to a target SpO2 (90%±1 if hypercapnic; 94%±1 if not hypercapnic) before commencing data collection. The titration protocol was structured such that a minimum of 5 minutes would pass between conditions to also serve as a washout period. Each condition lasted 20 minutes in total. SpO2 and heart rate data were gathered each minute, and oxygen volume reading was gathered every 5 minutes. After 20 minutes of using the oxygen delivery condition, subjects were asked to rate their subjective dyspnea and discomfort. After both conditions were completed, a final review of vital signs and overall stability was obtained before ending the study.

Randomization and Masking

Randomization of the study condition order was done to address any sequence effects that might be present. The randomization process followed published envelope concealment methodology,26,27 utilizing opaque envelopes, 10 of which include OXFO Condition on a sheet of paper inside, and 10 of which include Standard Condition. Batch randomization was performed, separately for male and female subjects (marked accordingly with “M” or “F”) in groups of 4-2-4. For each batch, an equal number of envelopes were pulled from each study condition and then combined and shuffled at random. Then a sequential number was written on the envelope in pen hard enough to transfer to carbon paper inside the envelope. The process was repeated until all 10 envelopes were sequenced for each sex (20 total). Each container of envelopes (one for male and one for female subjects) was delivered to the research team upon site initiation. Upon successful enrollment and completion of screening procedures, the research coordinator selected the next sequentially numbered envelope from the appropriately marked box for male or female subjects, opened the envelope, and recorded the randomization sequence in the subject’s case report form.

While the randomization sequence was concealed, the masking of staff or subjects was not possible due to differences between the delivery methods. The delivery of continuous oxygen creates an easily perceptible continuous sound and tactile sensation due to the constant flow of oxygen, whereas the OXFO System produces different intermittent sensations with inhalation and sounds only when the valve opens to refill the reservoir bag. Additionally, the masks and cannulas used for each condition were different. To minimize bias, research staff were instructed to place study equipment to the side of or behind the subject’s hospital bed to minimize their visual observation of the different equipment. They were also instructed to minimize discussion of the equipment, only to answer the subject’s questions during the informed consent process and remain technical in their answers rather than describe any potential benefits or discomforts that the subjects might expect with the OXFO System. Research staff received standardized training on the OXFO System which focused on technical operation, and it was emphasized that the current study aimed to answer questions about clinical outcomes and patient preferences that were not yet known.

Outcome Measures

In-line mass flow rate and volume of oxygen for both study conditions were measured by Digital Gas MEMS Mass Flow Meter Model MF5712 (0-200 L/min; 0.8 MPa; Siargo, Ltd.). The volume of oxygen dispensed was recorded at minute 0, minute 5, minute 10, minute 15, and minute 20 during each study condition. The total volume from minute 0 to minute 20 for each Condition was used in data analyses.

SpO2 and heart rate were assessed through the use of continuous pulse oximetry (Wellue® CheckmeO2™ Max Wrist Oxygen Monitor). During each study condition, readings were recorded every 1 minute by the study staff for a total of 21 readings including minute 0. SpO2 is a standard measure of blood oxygen saturation and is widely used across clinical settings globally. While there are other ways to measure blood oxygen saturation, such as arterial gas measures, we selected a peripheral measure to mirror real-world use settings of oxygen therapy. Guidelines for the use of oxygen therapy include SpO2 values to determine the clinical need for supplemental oxygen, as well as monitoring of patients by naming target ranges of SpO2 for effective therapy.28,29

Subject-reported tolerability was assessed using the Dyspnea Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) and Discomfort NRS, both of which were created for this study. These were administered on three occasions: screening, completion of Condition A, and completion of Condition B. The Dyspnea NRS asked “¿Cuanta falta de aire tienes ahora?” (in English, “How short of breath are you right now?”) with an 11-point scale anchored at 0- “ninguna en absoluto” (“none at all”) and 10- “la peor dificultad imaginable para respirar” (“worst shortness of breath imaginable”). The Discomfort NRS asked “¿Cuanta incomodidad sientes ahora mismo al respirar a través de esta mascara?” (“How much discomfort do you feel right now breathing through this mask?”) with an 11-point scale anchored at 0- “ninguna molestia en absoluto” (“no discomfort at all”) and 10- “la peor imaginable incomodidad” (“worst discomfort imaginable”).

All adverse events were recorded during the clinical study, whether serious or non-serious, related or unrelated to the study activities.

Data Analysis

With regard to the test of superiority for volume, the total amount of oxygen dispensed over the 20 minutes was calculated under OXFO Condition and Standard Condition. The ratio (OXFO Condition / Standard Condition) was computed for each subject, and the one-sample t-test was performed to compare the mean of this ratio with 1 (or as a percentage, to compare the mean of this ratio with 100%). The paired t-test was used to compare OXFO and Standard Conditions in terms of the mean amount of time within the SpO2 target range, the self-reported dyspnea rating, and the self-reported discomfort rating. The paired t-test for non-inferiority was used to test the hypothesis that the mean SpO2 for OXFO Condition is no worse than 2.8% lower (absolute difference) than the mean SpO2 for Standard Condition. This margin of 2.8% was selected based on the rationale that this corresponds to 70% of the minimal clinically important difference (4%) in SpO2 based on expert opinion described by Nagano and colleagues30 Power calculations were undertaken using differences and standard deviations in SpO2 and volume observed in the 2021 study with healthy subjects in which 20 subjects had power >0.99 to detect differences in volume and difference above the non-inferiority margin in SpO2. Subsequent assessments of association with demographic and health variables as well as time in the target range are exploratory. Multivariable linear regression was used to assess associations between the primary outcomes (ratio of oxygen dispensed and difference in SpO2 between the conditions) and physical characteristics that might affect OXFO’s performance (age, sex, weight, and SpO2 target range), as well as the randomization order to check for the effects of equipment acclimatization and study duration. The analysis was conducted via R (v4.1.1, R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). The significance level was set at α=0.05.

RESULTS

Twenty subjects (10 male, 10 female) were screened, randomized, and completed the study. No subjects dropped out or were withdrawn from the study, and there were no missing data for any subjects. Sample characteristics at screening are displayed in Tables 2 and 3. One subject’s data (a 68-year-old male randomized to receive Standard Condition first) was excluded from analyses due to a protocol deviation in which the subject was not titrated properly for Standard Condition. Qualitative conclusions did not change when this subject was included in the sample.

A summary of the main outcomes is displayed in Table 4. When considering the dispensing of oxygen as a ratio (OXFO Condition / Standard Condition) for each subject, the mean of this ratio was 7.7% (standard deviation (SD)=5.4%; range=0-20%) and this was significantly different from 100% (P<0.001). In other words, OXFO Condition produced a mean savings of 92.3% (SD=5.4%), or almost 13x savings compared to Standard Condition. Among all subjects, the smallest savings was 80%. The mean volume dispensed across subjects in OXFO Condition was 3.58 L (SD=2.52) and 51.53 L (SD=27.04) for Standard Condition (Figure 5). Figure 7 displays the volume dispensed for each subject during each condition. Linear regression revealed no significant associations between sex, weight, age, randomization order, or SpO2 target range, with the ratio of oxygen dispensed (Table 5).

The test for non-inferiority of OXFO Condition was significant (P<0.001) and no individual subject’s mean difference of Standard Condition SpO2 from OXFO Condition SpO2 was greater than the non-inferiority margin of -2.8%. Mean SpO2 was similar across conditions (Table 4; Figure 8). Linear regression revealed no significant associations between sex, weight, age, randomization order, or SpO2 target range with the difference in SpO2 between conditions (Table 6).

Subject-reported tolerability for the OXFO System was similar to conventional continuous flow (Table 4). Zero adverse events were recorded during the study. All subjects completed the study visit in its entirety.

The titration for Standard Condition resulted in flow rates ranging from 0.7 L/min to 6.0 L/min to achieve the target SpO2. There was a correlation of 0.29 between the Standard Condition flow rate and the savings with OXFO Condition, but this was not significant (P=0.23). OXFO Condition was inside the target SpO2 range for a mean of 18.8 readings (SD=3.04; 89.5% of 21 readings) while Standard Condition had a mean of 19.9 readings (SD=2.5; 95.0% of 21 readings) and the difference was not significant (P=0.28).

DISCUSSION

The co-primary endpoints of this study were met, finding both significant savings in the volume of oxygen dispensed with the OXFO System and the non-inferiority of the OXFO System to achieve a therapeutic dose measured by mean SpO2 compared to conventional continuous flow. The mean oxygen savings of almost 13x is surprising as we expected a savings of about 5x based on bench testing. In this study, the OXFO System was titrated (i.e., oxygen concentration diluted) to each subject’s saturation needs, reflecting a more accurate behavior of the device in a clinical population. Another contributing explanation for such low oxygen volumes may be the degree of sensitivity of the flowmeters used, which is discussed below in the limitations section. A mean of 13x savings while achieving a mean SpO2 that is comparable to the standard of care is a significant outcome for this novel oxygen delivery device. These large savings open an avenue for greater impact on the cost and accessibility of oxygen, particularly in LMICs.

The OXFO System also demonstrates the capacity to sustain oxygen savings across a continuum of doses. The lack of a significant correlation between the ratio of volume savings and the flow rate in Standard Condition is consistent with the conservation of nearly 13x remaining steady across subjects’ dosing needs up to 6 L/min. A positive (but not significant) estimated correlation suggests a possible small increase in savings with increased dose demands, but larger sample sizes would be needed to establish this. While there is an absence of published data on savings across dose demands, our findings are promising that this device can maintain efficiency and savings while achieving clinical targets for patients requiring higher doses.

Further, time in the target SpO2 range for the OXFO System (89.5%) was not significantly different from conventional continuous flow delivery (95.0%). This observed difference is also practically small relative to the long-term performance of continuous flow oxygen during hospitalization which is reportedly poor at around 50% of the time in range despite 24-hour medical monitoring.31–33 As these were exploratory analyses, a future study should be conducted to examine the stability of savings across the continuum of doses and the maintenance of target saturation over time.

Subjects appear to tolerate the OXFO System similarly to conventional continuous flow delivery by their self-report of dyspnea and discomfort. This is promising for the OXFO System given that it requires a larger high-flow nasal cannula and large-diameter corrugated tubing to reduce flow resistance during inhalation. In addition, it was anticipated that some subjects might associate the continuous sound and tactile sensation of conventional continuous flow delivery with a reassurance that they are receiving oxygen and, conversely, become anxious with the absence of this with the OXFO System. However, similar ratings across conditions are encouraging that subjects do not object to these sensory differences.

The potential impact of robust savings of close to 13x for patients at higher doses of 6 L/min is promising for achieving further access to oxygen and reducing costs. The OXFO System could provide the opportunity to conserve in the hospital setting, which is currently an underutilized avenue to address the oxygen crisis. Typically considered insignificant in cost and impact for high-income countries, the waste through the continuous flow can indeed add up to have an impact. The ability to achieve oxygen conservation at higher doses produces more available supply for a greater portion of the population. For example, if one adult patient requires 6 L/min continuous flow oxygen for 1 day, a total of 8,640 L would be dispensed over the day for their care. With the OXFO System, approximately 666 L would be dispensed to achieve the same clinical care, and the remaining 7,974 L would be available for other patients. This savings could provide a daily requirement of oxygen at 2 L/m continuous flow for approximately 2.75 other patients. However, if these other 2.75 patients were also to utilize an OXFO System, the savings would be greater and the existing oxygen supply would provide even more patients access to adequate oxygen.

Oxygen waste also occurs in hospital settings when continuous flow oxygen sources are not closed while the patient is away from the source. For example, a patient utilizing oxygen is taken to another unit for imaging for 2 hours while the bedside wall port is left open for that time, or the bedside concentrator is left running. Patients might remove the mask or cannula to eat or use the bathroom and do not always promptly replace the cannula. If the OXFO System were deployed across a hospital, all of this oxygen waste would no longer be a concern for the staff to monitor and manually open and close oxygen sources throughout the day.

Similarly, the OXFO System could play a role in the solution for pandemic/endemic and natural disaster preparedness. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, many institutions are planning large-scale and costly solutions for increasing oxygen plants and hospital infrastructure needed to store larger supplies.8 Relying on an increase in supply in turn relies on increased delivery trucks and qualified drivers, who may be incapacitated in the event of a pandemic.8 Alternatively, the OXFO System can attach directly to a hospital wall port and receive oxygen at 50 pounds per square inch (psi), requiring no special infrastructure changes to implement oxygen conservation. Deploying these devices hospital-wide could create a substantial buffer in the case of a surge in demand for oxygen or lack of supply in cases of natural disasters.

Several limitations in this study could be addressed in future research. First, the data are from a single study center in Colombia, a middle-income country in a major city, and may not generalize to all healthcare facilities, systems, regions, and conditions. Future studies could involve multiple centers and regions (ex. rural, suburban) to test the replicability and generalizability of these data. Second, while the 20-subject sample was sufficient per the sample size calculation for the primary hypothesis, this may not have been sufficient to identify potential tolerability concerns or special issues regarding different demographics or clinical characteristics. The eligibility criteria intentionally aimed to enroll acutely ill patients who had stabilized as measured by vital signs and time since certain medical events, such as surgery. While this limits the generalizability to all patients requiring medical oxygen, this does target a majority of typical hospitalized patients utilizing medical oxygen. Third, certain constructs were not accounted for in the study, such as willingness to participate, which may impact the measured outcomes. Similarly, with a small sample, we did not stratify by disease or symptom characteristics, such as respiratory diagnosis, symptom severity, number of chronic diseases, and others that may affect outcomes and should be evaluated in future research.

A fourth limitation of this study is the relatively brief duration of 20 minutes. While extrapolations can be calculated with regards to oxygen savings, this assumes that a patient would need similar titrations to achieve target SpO2 over time with both continuous flow and OXFO System as is typical of clinical care. Future research should evaluate the OXFO System’s performance over longer periods, such as 24 hours or an entire hospital stay. This would inform important economic and clinical targets such as the cost of hospitalization and time to discharge. Fifth, the endpoint of mean SpO2, while a clinically meaningful measure, may not capture all relevant and meaningful effects of the OXFO System compared to continuous flow delivery of medical oxygen. Future research can consider evaluating other endpoints such as time in and out of target SpO2, time to discharge, relevant disease outcomes, and ambulation during hospitalization.

Finally, the flowmeter equipment selected may not have been able to provide as precise a measure as anticipated. The flowmeters for OXFO Condition were placed between the pressurized tank and OXFO, therefore measuring the volume of oxygen being transferred from the tank to the OXFO reservoir, which holds a total of 2.5 L. Flowmeters that measure high flows up to 200 L/min were selected because the rate of this flow from the tank to OXFO is set to 50 psi. High flows typically imply high volumes, and therefore these flowmeters measure volume to the nearest 1 L. We did not anticipate such small volumes to be consumed by the subjects in OXFO Condition and a more specific measure of volume, such as to the 1/10 L or 1/100 L, would have been ideal. For example, one subject had a total volume of 0 L in OXFO Condition, despite meeting screening criteria of oxygen dependency and 20 of the 21 SpO2 readings being within the target SpO2 range. In this case, it is possible that the 2.5 L reservoir had just been refilled prior to the onset of the condition, and the subject withdrew up to 1.5 L over 20 minutes prior to another refill being triggered by the reservoir sensors. In future studies, a more precise flowmeter would help measure the use of oxygen more accurately.

CONCLUSIONS

The OXFO System saves a significant volume of oxygen and proves not inferior in achieving mean saturation when compared to conventional continuous flow delivery of oxygen among hospitalized oxygen-dependent patients. The OXFO System appears to maintain a robust volume savings of nearly 13x across a continuum of doses up to 6 L/min. This novel method holds promise to greatly impact LMICs and extend oxygen conservation to hospital settings thereby creating greater and more equitable access to medical oxygen. Future research should evaluate the OXFO System with patients across settings, dose demands, and fluctuations in activity levels to test this method’s ability to maintain saturation while sustaining oxygen savings.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was reviewed and approved by the Hospital Alma Máter de Antioquia Research Ethics Committee and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05677009).

DATA AVAILABILITY

Access to data supporting the reported results is available upon request, please contact the corresponding author.

FUNDING

OXFO Corporation

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTIONS

-

KMW: literature search, study design, manuscript preparation, review of manuscript

-

GH: study design, analysis of data, manuscript preparation, review of manuscript

-

SCOU: data collection, review of manuscript

-

RAOM: study design, manuscript preparation, review of manuscript

-

AB: study design, review of manuscript

-

DD: study design, review of manuscript

-

BY: study design, manuscript preparation, review of manuscript

-

CFB: literature search, study design, manuscript preparation, review of manuscript

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and declare the following activities and relationships:

-

Kelly Wawrzyniak is a paid consultant for OXFO Corporation

-

Giles Hooker is a paid consultant for OXFO Corporation

-

Susana Cristina Osorno Upegui works for an institution that received a research grant from OXFO Corporation

-

Rommer Alex Ortega Martínez works for an institution that received a research grant from OXFO Corporation

-

Adriana Bazoberry is a paid consultant for OXFO Corporation

-

David J DiBenedetto has a financial investment in OXFO Corporation

-

Brent Young is a founding partner of OXFO Corporation, and holds multiple patents pending related to OXFO System.

-

Carlos F Bazoberry is a founding partner of OXFO Corporation, and holds multiple patents pending related to OXFO System.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Kelly M Wawrzyniak, PsyD

110 Fairway Road, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, 02467, USA

[email protected]

+1 585 820 4048

_dispensed_during_each_treatment_conditio.tiff)

.tiff)

_of_all_subjects_during_each_treatment_condition_(n_19).tiff)

_dispensed_during_each_treatment_conditio.tiff)

.tiff)

_of_all_subjects_during_each_treatment_condition_(n_19).tiff)