The CardioVascular Clinical Trialists Middle East, Mediterranean and Africa (CVCT-MEMA) organisation, offers an international multi-stakeholder platform aggregating academic, pharmaceutical, Clinical Research Organisation (CRO), and some government policy makers, with the aim of drawing a roadmap towards reforming and harmonisation of the regulatory framework and sustainable capacity building. There are promising initiatives in few countries in the region such as Egypt, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and South Africa, aiming at scaling up the local clinical trials regulations to international standards that should serve as a benchmark for the other countries. Various clinical research centres in some countries, mostly affiliated with academia, oversee and implement clinical trials under a licensed regulation by the country’s Ministries of Health. Overall, progress is being made toward higher standards of human subjects’ protection, adequate functioning of ethics review systems, streamlined authorisation timelines, and contained bureaucracy. Clear and practical recommendations aiming at achieving a concrete roadmap to help the region to developing its own health knowledge production enterprise are provided.

“All nations should be producers of research as well as consumers”.1

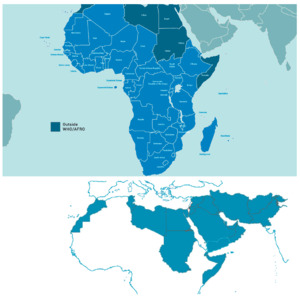

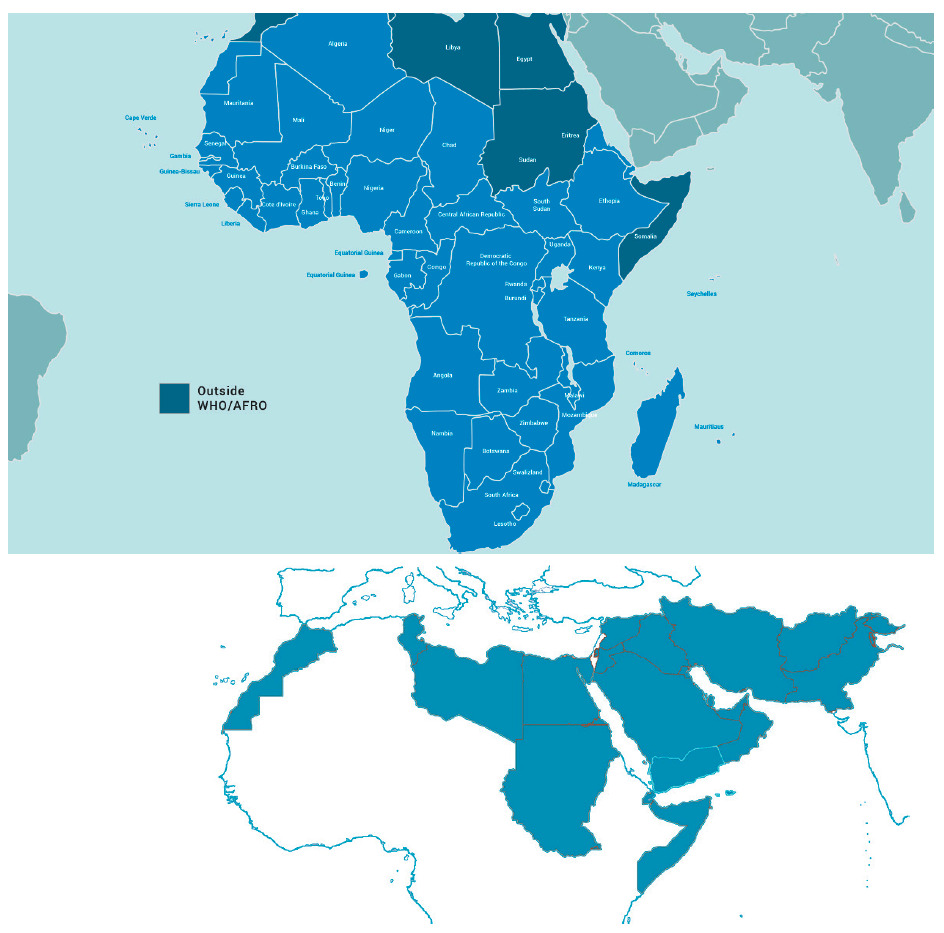

The WHO “EMRO” (East Mediterranean Region Organisation) is one of the six geographical areas designated by the WHO, stretching from Morocco to Pakistan. It covers 21 countries and represents a population of nearly 600 million. This adds up to the WHO “AFRO” (African Regional Organisation) region 47 countries representing 1 billion inhabitants, composing the 68 Middle East, Mediterranean, Africa (MEMA) region countries, totalling a population of over 1.6 billion ie, 20% of the world. The current state, existing infrastructure, and future recommendations to facilitate medical research in this region is the focus of the this white paper (Figure 1).

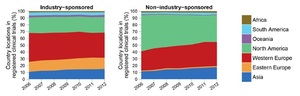

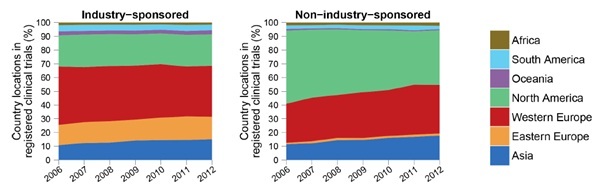

Although very diverse in terms of ethnicity, religion, culture, language, level of income distribution, and health care status and systems, most countries in the MEMA contribute little to the international effort of health knowledge production, despite a significant progress over the last two decades. Health research output should mirror the health needs and disease burden of a nation but this remains a disparity for many countries in the MEMA region. Although Huffman et al. noted a 36% increase in cardiovascular research output globally between 1999-2008, they found an inverse relationship between CVD publications and CVD burden and a direct positive relationship of CVD publications with the human development index. Low-middle income countries represented in the MEMA region with the highest burden of CVD continue to have lower research output than high income countries.2,3 The Region thus remains a consumer rather than a producer of health research data. However, progress is being made as is evident by the fact that Pakistan and Egypt, both WHO East Mediterranean Region Organisation countries, had highest rises in published research output in 2018. Other emerging economies also show some of the largest increases in research output in 2018.4 According to estimates from the publishing-services company Clarivate Analytics, Pakistan and Egypt topped the list in percentage terms, with rises of 21% and 15.9%, respectively.4 Despite this encouraging trend, MEMA countries, representing 20% of the global population, are host only to 6% of the worldwide trials registered in the latest international trial registries, such as clinicaltrials.gov and the WHO international Clinical Trials Registry 5 (Figure 2). Three countries are leading the charge in this respect, mainly Iran, followed at a distance by South Africa and Egypt. This discrepancy is not specific to the MEMA region and is common to middle- and low-income countries that contribute far less than high income ones to the global efforts of clinical trials.5 This issue is especially important as it represents a significant imbalance between the burden of disease prevalent in these countries and the global distribution of clinical research. Another important and less explored aspect is the translation of clinical trial findings to populations of different ethnic and genetic backgrounds.6,7 Populations in lower-income countries receive less attention than populations in high-income countries, and research on diseases of poverty in low and middle-income countries has become a global priority.

Among the many weaknesses of clinical research in MEMA are the cultural gap and lack of recognition for the need of developing a genuine clinical research infrastructure locally that is robust and sustainable. Access to technology, including to digital technologies, is suboptimal. There is unequal distribution of health research professionals, lack of strong experienced research networks, challenging political environment, and importantly, lack of a robust, internationally acceptable, regulatory framework. Despite this, the Region has a number of attractive features, such as population’s size and large pool of eligible patients, least trial saturated of all regions, diversity in genetic profile, lifestyle, and eating habits, and large medication-naive patient populations. In many countries, a relatively well distributed and advanced health care system has developed over time with competent doctors (many trained in established centers in the West who have now settled in MEMA region and have in turned trained local medical professionals) and health care professionals, and access to cost effective and not just “low cost” healthcare. Finally, and importantly, a very large pool of capable diaspora clinical scientists, with established experience in clinical research and international leadership in western countries are more than willing to help advising, and/or working locally in the Region, toward building and/or consolidating the environment for an accountable, responsible and professional clinical research, oriented toward Regional disease burden priorities. Moreover, participating in clinical trials can enhance the development of healthcare systems and qualification of clinical staff.

MEDICAL REGULATORY FRAMEWORKS IN MEMA COUNTRIES

Sound medical regulatory systems are critical for protecting public health against use of medical products which do not meet international standards of quality, safety and efficacy. Countries in the Region have National Medicines Regulatory Authorities (NMRAs) with varying organizational set-up and processes and standards.9,10 Performances in quality control, post-marketing surveillance, pharmacovigilance and clinical trials oversight is unequal and despite significant progress, much remains to be done especially in the area of clinical trials regulatory environment.

According to the WHO, only 7% of African countries have moderately developed capacity with more than 90% having minimal or no capacity in this respect.11 Ineffective regulatory systems are the main reason of marketing of unsafe and inefficacious products as well as of falsified and counterfeit medical products. It also creates barriers to free movement of products and access between countries, depriving patients of much needed products and depriving health industry from profitable business opportunities. Most countries import or produce generic medications with a total lack of or ineffective control of the quality, bioequivalence, safety and efficacy of such generic drugs. Very few countries have operational bioequivalence centres, most often because of the lack of regulations of trials with “healthy volunteers” participants.

Many African and international organisations such as the African Vaccines Regulatory Forum, African Medicines Regulatory Harmonization Initiative, Network of Official Medicines Control Laboratories and WHO, offer help to individual countries for strengthening their regulatory capacities. Plans for a potential establishment of the African Medicines Agency (AMA) in 2018 is an opportunity to improve NMRAs’ capacity in Africa.12

In this respect, we believe that clinical trial regulations and organisation, and local implementation and execution of clinical trials in the Region are key elements of the overall medicine regulatory framework.

Clinical research regulations in the MEMA Region

The above-mentioned plans for a potential establishment of the African Medicines Agency do not seem to have sufficiently considered specifically clinical trials regulations. One single paragraph in a 19 page document is dedicated to the clinical trial regulations, emphasizing the need for coordination on issues of clinical trials at the continental level, brought about only recently by the advent of the Ebola Virus Disease. This document states the following:

“Each member state within the African Union shall be responsible for the oversight and authorisation and ethical approval of clinical trials. The African Medicines agency (AMA) shall establish a continental Technical Working Group on clinical trials oversight and ethics approval of multicentre trials and create a clinical trial database which will track each trial being undertaken on the continent to enable other member states to benefit from results and challenges faced in those clinical trials. AMA will provide scientific review and guidance to National Medicine Regulatory Authorities (NMRAs) and sponsors where necessary and also provide a platform for sharing of knowledge on specific trials to avoid duplication of efforts and avoidance of possible challenges. AMA will work closely with other organizations such as the Africa CDC, the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials partnership (EDCTP) and the World Health Organization (WHO) in harnessing research and development and strengthening clinical trials oversight and ethics review capacity to facilitate approval of medical products and health technologies.”

Although laudable, this statement may remain wishful thinking, short of the development of a clear roadmap toward a harmonized Regional regulatory framework. Indeed, among the 47 AFRO countries in the Region, only a handful have comprehensive unified legislations. Most countries need to reform their guidance for overseeing and/or executing clinical trials. The situation in the 21 EMRO countries is less critical, although a significant overhaul is needed in most of these countries in order to align with international requirements and standards.

THE CVCT INITIATIVE

Since clinical research regulations should be incorporated in national regulations, issued by national experts, and voted by national parliaments, national initiatives and potential multinational efforts must be initiated and driven by local governments. However, given the global framework of clinical research, national regulations should inevitably converge and ideally be harmonized with the body of international regulations. Because national governments are making progress at different but very slow pace, with differing levels of priorities, we believe that bottom-up initiatives, helped by pertinent stakeholders, such as investigators, industry R&D experts, patient organisations and other health care professionals’ must coalesce in an overarching effort to help health authorities in the region scaling up and harmonizing their national regulations.

The CardioVascular Clinical Trialists Middle East, Mediterranean and Africa (CVCT-MEMA) organisation,13 affiliated to the CVCT global initiative, offers such an international multi-stakeholder platform capable of a bottom-up initiative of working towards the much-needed reform and harmonisation of the regulatory framework and towards a sustainable capacity building in the Region.

In September 2018, CVCT MEMA held a regulatory summit for 2 days in Cairo, Egypt to discuss the clinical research community’s ideas and challenges as well as the recommendations going forward on a regional level. Indeed, cardiovascular disease is one of the medical areas where practice is most driven by robust clinical evidence, stemming from well-designed clinical trials. It was intended that the experience accumulated by international and local experts in this area may serve as a case study and a starting point, which may be applied to other disease areas.

Proceedings of the Regulatory Summit at CVCT MEMA 2018

The regulatory summit was intended to provide the opportunity for experts/representatives from regulatory bodies; competent authorities and ministries of health representatives assemble and discuss ways to learn from each other and scale up local regulations to international standards. Experts were also invited to share and debate their conclusions with health care professionals at one full day public workshop.

This white paper describes these deliberations, discussions and recommendations that represent the aggregated academic, pharmaceutical, Clinical Research Organisation (CRO), and some government policy views. As a matter of fact, CVCT meetings are oriented toward brainstorming and intense interaction, among leaders from various backgrounds assembling in a unique think tank. CVCT MEMA meetings assemble representatives from Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, Tunisia, Egypt, Lebanon, Oman, Jordan, Turkey, Pakistan, and Iran, with international representatives from Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and USA. These include clinicians, epidemiologists, clinical trialists, policy makers, industry experts, regulatory experts, and international organisations, such as the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and WHO. Health care systems in these mostly EMRO countries are diverse but they share more common economic, epidemiological and environmental features than with other regions in the world.

The latest conference, the third one since the CVCT initiative inception, was held on 13th of September 2018 in Cairo. It assembled ministers and other major stakeholders discussing the clinical research landscape in the region, the best practices of clinical trial application authorisation, pharmacovigilance and safety reporting as well as the state of local regulations regarding bioequivalence studies. The conference also included two master classes focusing on interpreting results of clinical trials as well as how to design and interpret a registry study. The conference was concluded by an executive summary session where panellists from international regulatory bodies, regional pharmaceutical and CRO industry representatives as well as government policy representatives, a representative from the European Medicines Agency, and principal investigators from various Egyptian and international universities added their remarks on the regional roadmap and recommendations for the Region clinical research landscape, with Egypt as a case study, in the light of its recently drafted law, its articles, provisions and recommended amendments.

THE NEED FOR CLINICAL TRIALS, EVIDENCE GENERATION AND LOCAL QUALITY HEALTH DATA

Clinical research provides robust ways of investigating the safety, clinical benefit and cost effectiveness of treatments, inerventions, or other aspects of healthcare provision. Health policy and health industry decision-making and investment, shaping up sustainable and responsible health care systems should rely on optimal quality health data. The contribution of the MEMA region to high standard health knowledge and actionable data is an important unmet need. Health policy and clinical practice in the Region should improve to be more data-driven and more evidence-based as to offer better and more cost-effective health care to the patients in the Region. Obviously, healthcare in the Region cannot be driven by the simple transposition of evidence and health data collected in high income and/or Northern/Western countries. Increasing the contribution of local investigators and health care professionals to the global clinical research effort and generating a genuine local clinical data is an important priority for all health care professionals and policy makers in the Region.

CURRENT STATE OF THE CLINICAL RESEARCH REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

There has been an increase in clinical trials conducted in the Middle East and North Africa region in recent years, largely due to the prevalence of various communicable and non-communicable health challenges including cardiovascular, oncological and infectious diseases.

There are various clinical research centres in some countries, mostly affiliated with academia, that oversees and implements clinical trials under a licensed regulation by the countries’ Ministry of Health. The trials are generally conducted in accordance with the local and international regulations of the ICH-GCP (ICH - International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use; GCP - Good clinical practice) guidelines. However, there are numerous challenges in regard to the implementation of these trials, mainly due to lack of a national regulatory law, paucity of research infrastructures or institutional review mechanisms in institutions desiring to participate in large scale clinical trials, as well as uncertain public confidence and poor awareness of the importance and the objectives of clinical research.

In general, there is a paucity of registered clinical trials performed in the Region, with a low rate of publication (around 50%) of locally performed trials, comparable to what is being reported in the current literature in other countries. The common non-inclusion of local investigators in the authorship of most of the studies reflects that they had no leadership role.

Case studies from selected countries

Egypt

The law for regulation and control of clinical trials in Egypt dates back to 2005. After various rounds of drafting, the law was introduced to the Egyptian parliament in May 2018 amid significant objections from the academia and principal investigator community as well as the industry, the main stakeholders of the success and implementation of such discipline. Most recently, a new committee has been nominated for further work on clinical trial regulations.

Egypt a country of 100 million people, is the second-biggest destination country for clinical trials in Africa, hosting a rising number of trials, which has tripled between 2008 and 2011.14 Most trials were sponsored by big pharma companies seeking off-shoring clinical trials in low- and middle-income countries.

Saudi Arabia

The Saudi Food and Drug Authority has created probably one of the most advanced regulatory frameworks, which, together with high level of income, world-class medical facilities, western-trained investigators and a large and growing pharmaceutical market are likely to contribute to Saudi Arabia’s attractiveness for clinical trials.15

Lebanon

Lebanon also several waves of laws and decrees from the Ministry of public health in 2014 and 2016 are regulating clinical trials and institutional review boards and starting using the an online WHO International Clinical Trial Registry Platform (ICTRP), making Lebanon the second country after Iran in the EMRO to use this Registry.

Tunisia

In early 2015, Tunisian government issued a series of decrees scaling up the local clinical trials regulations to international standards, including the adoption of Good Clinical Practice, healthy volunteers’ and vulnerable patients’ participation in trials and central committees of protection of participants in clinical research, to replace multiple dispersed ethics committees. Within the post ‘Jasmin revolution’ context and amid multiple change of governments, the new regulatory framework is being slowly and progressively implemented. Tunisia, one of the smallest countries in the Region hosts a relatively large number of trials, relative to its population.

South Africa

In South Africa,16 the single country hosting the largest number of trials in the Region, a comprehensive set of good clinical practice was made available back in 2006 and, as of June 1, 2017, the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) was established as the regulatory authority overseeing medicines and clinical research. Constant progress is being made, year on year, toward an attractive international grade clinical trials legislation.17

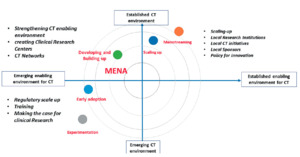

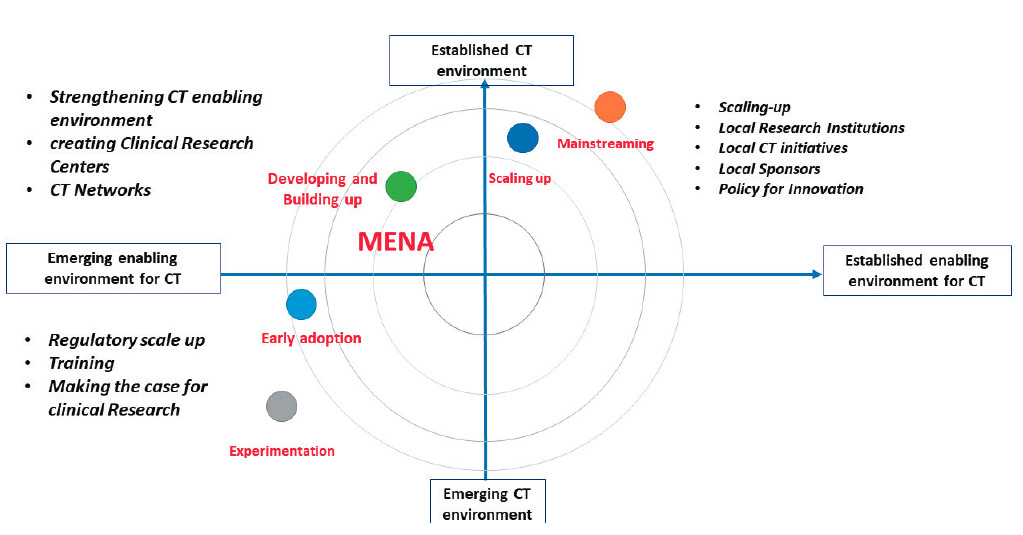

These “case studies” in Tunisia, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and South Africa, exemplify a variety of degrees of advancement among countries in the Region (Figure 3).

The current state of clinical trials regulations in a selected number of countries is summarized in Table 1.

Common recent trends

A fair assessment of the situation, overall, is that progress is being made toward higher standards of human subjects’ protection, adequate functioning of ethics review systems, streamlined authorisation timelines, and contained bureaucracy. A report from the WEMOS18 foundation, compiled four country reports on the clinical trials industry: Egypt, Kenya, Zimbabwe, and South Africa. Findings clearly show ethical concerns in conducting clinical trials in these countries, because they often do not have robust legislative and regulatory frameworks in place. On another hand, there are reports of noticeable efforts to regulate research ethics in certain countries in the Region.19 Most of new regulations across countries tend to contain the majority of protections mentioned in the international guidelines related to research ethics. But progress is still needed across the Region for clinical trials review boards 20 towards setting rules for membership, accreditation, training, functioning, and capacity of reviewing protocol and monitoring studies. Frequently reported unmet needs are: clarifying the objectives and respective duties of the multiple and redundant national ethics boards, local ethics committees and institutional review boards, and defining an authority hierarchy, if not merging into a single model of review boards in respective countries.

THE CVCT CONFERENCE RECOMMENDATIONS

The conference recognised the need to promote major enablers such as i) training of relevant healthcare professionals in clinical research, ii) building clinical research capacity with sustainable investigator networks and dedicated professional clinical research centres, iii) moving toward digital health. And iv) creating a favourable environment for funding clinical research and attracting clinical trials.

Reforming The Regulatory Framework:

After having reviewed the unmet needs, the multi-stakeholder multi-national experts at the regulatory summit agreed on a set of recommendations for speeding the needed regulatory framework reform in the Region, targeting the highest international standards, ideally harmonising national regulations in a single set of regulations, possibly benchmarking what Europe has developed over the last 20 years at the European Medical Agency (Box 1).

Capacity building:

An important aspect of bridging the “10/90” gap29 is country specific indigenous research capacity development. Indeed, objective 5 of the WHO global action plan for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases is to " promote and support national capacity for high quality research and development for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases".30 This includes developing a cadre of well-trained investigators and clinical research health care professionals, locally operating clinical research organisations (CROs), ideally within the setting or under the leadership of academic professionals and academic CROs. This is a critical endeavour which may reverse the current endemic practice of “parachute research” and/or “hit and run research” whereby research teams from western high-income countries and/or major CROs conduct their own research involving local investigators only for the limited purpose of a given study and then leave, typically “off shoring” clinical trials, with no sustainable capacity building.

An appraisal of the current situation of clinical trials capacity building in Egypt has been reported recently and highlights an original experience of the Tanta University.

In Tunisia, a new medical research directorate was created in 2015 within the Ministry of Health, complementing the Research Directorate in the Ministry of Higher Education, which achieved the up-grading of the Tunisian regulations for clinical research and the funding and launching of 5 Clinical investigation centres (CIC) in 4 different university hospitals and one in Pasteur Institute, benchmarking the INSERM CICs models in France.

Sub-Saharan Africa aims for more research autonomy, and some infrastructure is being developed, such as the Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa. The European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP), a European Union-funded and peer-review grant awarding agency, initiated the concept of the regional Networks of Excellence led by African professionals to champion clinical trials capacity development, research excellence and networking, in partnership with European member states. Other South-North-South partnerships can be of high value in building sustainable research capacity in low- and middle-income countries. Many other opportunities for capacity building programs based on good collaborative practice exist. The American University of Beirut ranks among the world elite’s in scientific medical research.31 The above mentioned various initiatives and institutions with recognized track records should serve as examples worth benchmarking and capitalizing in their respective governmental and non-governmental organizations and beyond, in the region.

Box 2 provides a tentative roadmap for scaling up clinical research in the Region. We hereunder elected to elaborate on 3 main priorities, providing more granular details on how to move toward with digital health, how to provide funding for clinical research and how to engage into capacity building.

Moving toward digital health

In most countries in the Region, the resources available to ensure quality data collection remain severely limited, mainly because of lack of source data or the use of only paper documents. Little data is available electronically. Few countries, such as Pakistan, are moving toward digital health, although most are well equipped and trained to move into the digital revolution, and have done so in business and banking and other areas. We suggest the development of eHealth policies with a primary focus of implementing electronic health records33 as part of a mutation to digital health. The roadmap34 drafted with experts from the WHO (National eHealth Strategy Toolkit) is an excellent tutorial for national health policy makers, as well as the US FDA.35

Funding of clinical trials

The lack of clinical studies focusing on non-communicable chronic diseases is a concern, considering the increasing burden of such health conditions in the Region.36 During the last 20 years the number of cardiovascular diseases-related deaths and the prevalence of diabetes almost doubled.37 The number of epidemiological reports from the Region is low, with a predominance of projected estimates used to characterize the pattern of cardiovascular risk and disease.38,39 In rural areas, communicable diseases, and rheumatic heart disease still predominate, with HIV-related CVD presenting a new communicable threat, more specifically in sub-saharan Africa. In more urban regions, hypertensive heart disease obesity, diabetes, coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, atrial fibrillation and related heart failure take the lead, as in western countries, with an even higher burden of cardiometabolic diseases in the Middle East. Compared with the global burden of cardiovascular disease, affected patients are typically younger, predominantly female, and mostly from disadvantaged communities. Still, there are persisting major knowledge gaps, despite the rising number of epidemiological studies, mostly from Middle East, few of which are published in international journals.The CardioVascular Clinical Trialists Middle East, Mediterranean and Africa (CVCT-MEMA) organisation, offers an international multi-stakeholder platform aggregating academic, pharmaceutical, Clinical Research Organisation (CRO), and some government policy makers, with the aim of drawing a roadmap towards reforming and harmonisation of the regulatory framework and sustainable capacity building. There are promising initiatives in few countries in the region such as Egypt, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and South Africa, aiming at scaling up the local clinical trials regulations to international standards that should serve as a benchmark for the other countries. Various clinical research centres in some countries, mostly affiliated with academia, oversee and implement clinical trials under a licensed regulation by the country’s Ministries of Health. Overall, progress is being made toward higher standards of human subjects’ protection, adequate functioning of ethics review systems, streamlined authorisation timelines, and contained bureaucracy. Clear and practical recommendations aiming at achieving a concrete roadmap to help the region to developing its own health knowledge production enterprise are provided.

“All nations should be producers of research as well as consumers”.1

The WHO “EMRO” (East Mediterranean Region Organisation) is one of the six geographical areas designated by the WHO, stretching from Morocco to Pakistan. It covers 21 countries and represents a population of nearly 600 million. This adds up to the WHO “AFRO” (African Regional Organisation) region 47 countries representing 1 billion inhabitants, composing the 68 Middle East, Mediterranean, Africa (MEMA) region countries, totalling a population of over 1.6 billion ie, 20% of the world. The current state, existing infrastructure, and future recommendations to facilitate medical research in this region is the focus of the this white paper (Figure 1).

Although very diverse in terms of ethnicity, religion, culture, language, level of income distribution, and health care status and systems, most countries in the MEMA contribute little to the international effort of health knowledge production, despite a significant progress over the last two decades. Health research output should mirror the health needs and disease burden of a nation but this remains a disparity for many countries in the MEMA region. Although Huffman et al. noted a 36% increase in cardiovascular research output globally between 1999-2008, they found an inverse relationship between CVD publications and CVD burden and a direct positive relationship of CVD publications with the human development index. Low-middle income countries represented in the MEMA region with the highest burden of CVD continue to have lower research output than high income countries.2,3 The Region thus remains a consumer rather than a producer of health research data. However, progress is being made as is evident by the fact that Pakistan and Egypt, both WHO East Mediterranean Region Organisation countries, had highest rises in published research output in 2018. Other emerging economies also show some of the largest increases in research output in 2018.4 According to estimates from the publishing-services company Clarivate Analytics, Pakistan and Egypt topped the list in percentage terms, with rises of 21% and 15.9%, respectively.4 Despite this encouraging trend, MEMA countries, representing 20% of the global population, are host only to 6% of the worldwide trials registered in the latest international trial registries, such as clinicaltrials.gov and the WHO international Clinical Trials Registry5 (Figure 2). Three countries are leading the charge in this respect, mainly Iran, followed at a distance by South Africa and Egypt. This discrepancy is not specific to the MEMA region and is common to middle- and low-income countries that contribute far less than high income ones to the global efforts of clinical trials.5 This issue is especially important as it represents a significant imbalance between the burden of disease prevalent in these countries and the global distribution of clinical research. Another important and less explored aspect is the translation of clinical trial findings to populations of different ethnic and genetic backgrounds.6,7 Populations in lower-income countries receive less attention than populations in high-income countries, and research on diseases of poverty in low and middle-income countries has become a global priority.

Among the many weaknesses of clinical research in MEMA are the cultural gap and lack of recognition for the need of developing a genuine clinical research infrastructure locally that is robust and sustainable. Access to technology, including to digital technologies, is suboptimal. There is unequal distribution of health research professionals, lack of strong experienced research networks, challenging political environment, and importantly, lack of a robust, internationally acceptable, regulatory framework. Despite this, the Region has a number of attractive features, such as population’s size and large pool of eligible patients, least trial saturated of all regions, diversity in genetic profile, lifestyle, and eating habits, and large medication-naive patient populations. In many countries, a relatively well distributed and advanced health care system has developed over time with competent doctors (many trained in established centers in the West who have now settled in MEMA region and have in turned trained local medical professionals) and health care professionals, and access to cost effective and not just “low cost” healthcare. Finally, and importantly, a very large pool of capable diaspora clinical scientists, with established experience in clinical research and international leadership in western countries are more than willing to help advising, and/or working locally in the Region, toward building and/or consolidating the environment for an accountable, responsible and professional clinical research, oriented toward Regional disease burden priorities. Moreover, participating in clinical trials can enhance the development of healthcare systems and qualification of clinical staff.

MEDICAL REGULATORY FRAMEWORKS IN MEMA COUNTRIES

Sound medical regulatory systems are critical for protecting public health against use of medical products which do not meet international standards of quality, safety and efficacy. Countries in the Region have National Medicines Regulatory Authorities (NMRAs) with varying organizational set-up and processes and standards.9,10 Performances in quality control, post-marketing surveillance, pharmacovigilance and clinical trials oversight is unequal and despite significant progress, much remains to be done especially in the area of clinical trials regulatory environment.

According to the WHO, only 7% of African countries have moderately developed capacity with more than 90% having minimal or no capacity in this respect.11 Ineffective regulatory systems are the main reason of marketing of unsafe and inefficacious products as well as of falsified and counterfeit medical products. It also creates barriers to free movement of products and access between countries, depriving patients of much needed products and depriving health industry from profitable business opportunities. Most countries import or produce generic medications with a total lack of or ineffective control of the quality, bioequivalence, safety and efficacy of such generic drugs. Very few countries have operational bioequivalence centres, most often because of the lack of regulations of trials with “healthy volunteers” participants.

Many African and international organisations such as the African Vaccines Regulatory Forum, African Medicines Regulatory Harmonization Initiative, Network of Official Medicines Control Laboratories and WHO, offer help to individual countries for strengthening their regulatory capacities. Plans for a potential establishment of the African Medicines Agency (AMA) in 2018 is an opportunity to improve NMRAs’ capacity in Africa.12

In this respect, we believe that clinical trial regulations and organisation, and local implementation and execution of clinical trials in the Region are key elements of the overall medicine regulatory framework.

Clinical research regulations in the MEMA Region

The above-mentioned plans for a potential establishment of the African Medicines Agency do not seem to have sufficiently considered specifically clinical trials regulations. One single paragraph in a 19 page document is dedicated to the clinical trial regulations, emphasizing the need for coordination on issues of clinical trials at the continental level, brought about only recently by the advent of the Ebola Virus Disease. This document states the following:

“Each member state within the African Union shall be responsible for the oversight and authorisation and ethical approval of clinical trials. The African Medicines agency (AMA) shall establish a continental Technical Working Group on clinical trials oversight and ethics approval of multicentre trials and create a clinical trial database which will track each trial being undertaken on the continent to enable other member states to benefit from results and challenges faced in those clinical trials. AMA will provide scientific review and guidance to National Medicine Regulatory Authorities (NMRAs) and sponsors where necessary and also provide a platform for sharing of knowledge on specific trials to avoid duplication of efforts and avoidance of possible challenges. AMA will work closely with other organizations such as the Africa CDC, the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials partnership (EDCTP) and the World Health Organization (WHO) in harnessing research and development and strengthening clinical trials oversight and ethics review capacity to facilitate approval of medical products and health technologies.”

Although laudable, this statement may remain wishful thinking, short of the development of a clear roadmap toward a harmonized Regional regulatory framework. Indeed, among the 47 AFRO countries in the Region, only a handful have comprehensive unified legislations. Most countries need to reform their guidance for overseeing and/or executing clinical trials. The situation in the 21 EMRO countries is less critical, although a significant overhaul is needed in most of these countries in order to align with international requirements and standards.

THE CVCT INITIATIVE

Since clinical research regulations should be incorporated in national regulations, issued by national experts, and voted by national parliaments, national initiatives and potential multinational efforts must be initiated and driven by local governments. However, given the global framework of clinical research, national regulations should inevitably converge and ideally be harmonized with the body of international regulations. Because national governments are making progress at different but very slow pace, with differing levels of priorities, we believe that bottom-up initiatives, helped by pertinent stakeholders, such as investigators, industry R&D experts, patient organisations and other health care professionals’ must coalesce in an overarching effort to help health authorities in the region scaling up and harmonizing their national regulations.

The CardioVascular Clinical Trialists Middle East, Mediterranean and Africa (CVCT-MEMA) organisation13, affiliated to the CVCT global initiative, offers such an international multi-stakeholder platform capable of a bottom-up initiative of working towards the much-needed reform and harmonisation of the regulatory framework and towards a sustainable capacity building in the Region.

In September 2018, CVCT MEMA held a regulatory summit for 2 days in Cairo, Egypt to discuss the clinical research community’s ideas and challenges as well as the recommendations going forward on a regional level. Indeed, cardiovascular disease is one of the medical areas where practice is most driven by robust clinical evidence, stemming from well-designed clinical trials. It was intended that the experience accumulated by international and local experts in this area may serve as a case study and a starting point, which may be applied to other disease areas.

Proceedings of the Regulatory Summit at CVCT MEMA 2018

The regulatory summit was intended to provide the opportunity for experts/representatives from regulatory bodies; competent authorities and ministries of health representatives assemble and discuss ways to learn from each other and scale up local regulations to international standards. Experts were also invited to share and debate their conclusions with health care professionals at one full day public workshop.

This white paper describes these deliberations, discussions and recommendations that represent the aggregated academic, pharmaceutical, Clinical Research Organisation (CRO), and some government policy views. As a matter of fact, CVCT meetings are oriented toward brainstorming and intense interaction, among leaders from various backgrounds assembling in a unique think tank. CVCT MEMA meetings assemble representatives from Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, Tunisia, Egypt, Lebanon, Oman, Jordan, Turkey, Pakistan, and Iran, with international representatives from Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and USA. These include clinicians, epidemiologists, clinical trialists, policy makers, industry experts, regulatory experts, and international organisations, such as the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and WHO. Health care systems in these mostly EMRO countries are diverse but they share more common economic, epidemiological and environmental features than with other regions in the world.

The latest conference, the third one since the CVCT initiative inception, was held on 13th of September 2018 in Cairo. It assembled ministers and other major stakeholders discussing the clinical research landscape in the region, the best practices of clinical trial application authorisation, pharmacovigilance and safety reporting as well as the state of local regulations regarding bioequivalence studies. The conference also included two master classes focusing on interpreting results of clinical trials as well as how to design and interpret a registry study. The conference was concluded by an executive summary session where panellists from international regulatory bodies, regional pharmaceutical and CRO industry representatives as well as government policy representatives, a representative from the European Medicines Agency, and principal investigators from various Egyptian and international universities added their remarks on the regional roadmap and recommendations for the Region clinical research landscape, with Egypt as a case study, in the light of its recently drafted law, its articles, provisions and recommended amendments.

THE NEED FOR CLINICAL TRIALS, EVIDENCE GENERATION AND LOCAL QUALITY HEALTH DATA

Clinical research provides robust ways of investigating the safety, clinical benefit and cost effectiveness of treatments, inerventions, or other aspects of healthcare provision. Health policy and health industry decision-making and investment, shaping up sustainable and responsible health care systems should rely on optimal quality health data. The contribution of the MEMA region to high standard health knowledge and actionable data is an important unmet need. Health policy and clinical practice in the Region should improve to be more data-driven and more evidence-based as to offer better and more cost-effective health care to the patients in the Region. Obviously, healthcare in the Region cannot be driven by the simple transposition of evidence and health data collected in high income and/or Northern/Western countries. Increasing the contribution of local investigators and health care professionals to the global clinical research effort and generating a genuine local clinical data is an important priority for all health care professionals and policy makers in the Region.

CURRENT STATE OF THE CLINICAL RESEARCH REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

There has been an increase in clinical trials conducted in the Middle East and North Africa region in recent years, largely due to the prevalence of various communicable and non-communicable health challenges including cardiovascular, oncological and infectious diseases.

There are various clinical research centres in some countries, mostly affiliated with academia, that oversees and implements clinical trials under a licensed regulation by the countries’ Ministry of Health. The trials are generally conducted in accordance with the local and international regulations of the ICH-GCP (ICH - International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use; GCP - Good clinical practice) guidelines. However, there are numerous challenges in regard to the implementation of these trials, mainly due to lack of a national regulatory law, paucity of research infrastructures or institutional review mechanisms in institutions desiring to participate in large scale clinical trials, as well as uncertain public confidence and poor awareness of the importance and the objectives of clinical research.

In general, there is a paucity of registered clinical trials performed in the Region, with a low rate of publication (around 50%) of locally performed trials, comparable to what is being reported in the current literature in other countries. The common non-inclusion of local investigators in the authorship of most of the studies reflects that they had no leadership role.

Case studies from selected countries

Egypt

The law for regulation and control of clinical trials in Egypt dates back to 2005. After various rounds of drafting, the law was introduced to the Egyptian parliament in May 2018 amid significant objections from the academia and principal investigator community as well as the industry, the main stakeholders of the success and implementation of such discipline. Most recently, a new committee has been nominated for further work on clinical trial regulations.

Egypt a country of 100 million people, is the second-biggest destination country for clinical trials in Africa, hosting a rising number of trials, which has tripled between 2008 and 2011.14 Most trials were sponsored by big pharma companies seeking off-shoring clinical trials in low- and middle-income countries.

Saudi Arabia

The Saudi Food and Drug Authority has created probably one of the most advanced regulatory frameworks, which, together with high level of income, world-class medical facilities, western-trained investigators and a large and growing pharmaceutical market are likely to contribute to Saudi Arabia’s attractiveness for clinical trials.15

Lebanon

Lebanon also several waves of laws and decrees from the Ministry of public health in 2014 and 2016 are regulating clinical trials and institutional review boards and starting using the an online WHO International Clinical Trial Registry Platform (ICTRP), making Lebanon the second country after Iran in the EMRO to use this Registry.

Tunisia

In early 2015, Tunisian government issued a series of decrees scaling up the local clinical trials regulations to international standards, including the adoption of Good Clinical Practice, healthy volunteers’ and vulnerable patients’ participation in trials and central committees of protection of participants in clinical research, to replace multiple dispersed ethics committees. Within the post ‘Jasmin revolution’ context and amid multiple change of governments, the new regulatory framework is being slowly and progressively implemented. Tunisia, one of the smallest countries in the Region hosts a relatively large number of trials, relative to its population.

South Africa

In South Africa16, the single country hosting the largest number of trials in the Region, a comprehensive set of good clinical practice was made available back in 2006 and, as of June 1, 2017, the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) was established as the regulatory authority overseeing medicines and clinical research. Constant progress is being made, year on year, toward an attractive international grade clinical trials legislation.17

These “case studies” in Tunisia, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and South Africa, exemplify a variety of degrees of advancement among countries in the Region (Figure 3).

The current state of clinical trials regulations in a selected number of countries is summarized in Table 1.

Common recent trends

A fair assessment of the situation, overall, is that progress is being made toward higher standards of human subjects’ protection, adequate functioning of ethics review systems, streamlined authorisation timelines, and contained bureaucracy. A report from the WEMOS18 foundation, compiled four country reports on the clinical trials industry: Egypt, Kenya, Zimbabwe, and South Africa. Findings clearly show ethical concerns in conducting clinical trials in these countries, because they often do not have robust legislative and regulatory frameworks in place. On another hand, there are reports of noticeable efforts to regulate research ethics in certain countries in the Region.19 Most of new regulations across countries tend to contain the majority of protections mentioned in the international guidelines related to research ethics. But progress is still needed across the Region for clinical trials review boards20 towards setting rules for membership, accreditation, training, functioning, and capacity of reviewing protocol and monitoring studies. Frequently reported unmet needs are: clarifying the objectives and respective duties of the multiple and redundant national ethics boards, local ethics committees and institutional review boards, and defining an authority hierarchy, if not merging into a single model of review boards in respective countries.

THE CVCT CONFERENCE RECOMMENDATIONS

The conference recognised the need to promote major enablers such as i) training of relevant healthcare professionals in clinical research, ii) building clinical research capacity with sustainable investigator networks and dedicated professional clinical research centres, iii) moving toward digital health. And iv) creating a favourable environment for funding clinical research and attracting clinical trials.

Reforming The Regulatory Framework:

After having reviewed the unmet needs, the multi-stakeholder multi-national experts at the regulatory summit agreed on a set of recommendations for speeding the needed regulatory framework reform in the Region, targeting the highest international standards, ideally harmonising national regulations in a single set of regulations, possibly benchmarking what Europe has developed over the last 20 years at the European Medical Agency (Box 1).

Capacity building:

An important aspect of bridging the “10/90” gap29 is country specific indigenous research capacity development. Indeed, objective 5 of the WHO global action plan for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases is to " promote and support national capacity for high quality research and development for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases".30 This includes developing a cadre of well-trained investigators and clinical research health care professionals, locally operating clinical research organisations (CROs), ideally within the setting or under the leadership of academic professionals and academic CROs. This is a critical endeavour which may reverse the current endemic practice of “parachute research” and/or “hit and run research” whereby research teams from western high-income countries and/or major CROs conduct their own research involving local investigators only for the limited purpose of a given study and then leave, typically “off shoring” clinical trials, with no sustainable capacity building.

An appraisal of the current situation of clinical trials capacity building in Egypt has been reported recently and highlights an original experience of the Tanta University.

In Tunisia, a new medical research directorate was created in 2015 within the Ministry of Health, complementing the Research Directorate in the Ministry of Higher Education, which achieved the up-grading of the Tunisian regulations for clinical research and the funding and launching of 5 Clinical investigation centres (CIC) in 4 different university hospitals and one in Pasteur Institute, benchmarking the INSERM CICs models in France.

Sub-Saharan Africa aims for more research autonomy, and some infrastructure is being developed, such as the Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa. The European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP), a European Union-funded and peer-review grant awarding agency, initiated the concept of the regional Networks of Excellence led by African professionals to champion clinical trials capacity development, research excellence and networking, in partnership with European member states. Other South-North-South partnerships can be of high value in building sustainable research capacity in low- and middle-income countries. Many other opportunities for capacity building programs based on good collaborative practice exist. The American University of Beirut ranks among the world elite’s in scientific medical research.31 The above mentioned various initiatives and institutions with recognized track records should serve as examples worth benchmarking and capitalizing in their respective governmental and non-governmental organizations and beyond, in the region.

Box 2 provides a tentative roadmap for scaling up clinical research in the Region. We hereunder elected to elaborate on 3 main priorities, providing more granular details on how to move toward with digital health, how to provide funding for clinical research and how to engage into capacity building.

Moving toward digital health

In most countries in the Region, the resources available to ensure quality data collection remain severely limited, mainly because of lack of source data or the use of only paper documents. Little data is available electronically. Few countries, such as Pakistan, are moving toward digital health, although most are well equipped and trained to move into the digital revolution, and have done so in business and banking and other areas. We suggest the development of eHealth policies with a primary focus of implementing electronic health records33 as part of a mutation to digital health. The roadmap34 drafted with experts from the WHO (National eHealth Strategy Toolkit) is an excellent tutorial for national health policy makers, as well as the US FDA.35

Funding of clinical trials

The lack of clinical studies focusing on non-communicable chronic diseases is a concern, considering the increasing burden of such health conditions in the Region.36 During the last 20 years the number of cardiovascular diseases-related deaths and the prevalence of diabetes almost doubled.37 The number of epidemiological reports from the Region is low, with a predominance of projected estimates used to characterize the pattern of cardiovascular risk and disease.38,39 In rural areas, communicable diseases, and rheumatic heart disease still predominate, with HIV-related CVD presenting a new communicable threat, more specifically in sub-saharan Africa. In more urban regions, hypertensive heart disease obesity, diabetes, coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, atrial fibrillation and related heart failure take the lead, as in western countries, with an even higher burden of cardiometabolic diseases in the Middle East. Compared with the global burden of cardiovascular disease, affected patients are typically younger, predominantly female, and mostly from disadvantaged communities. Still, there are persisting major knowledge gaps, despite the rising number of epidemiological studies, mostly from Middle East, few of which are published in international journals.40–44 Difficulties in the planning and implementation of effective health care in most African countries are compounded by a paucity of studies and a low rate of investment in research and data acquisition.40

Most of clinical research in the Region is funded by companies and led by investigators from high income western countries. This would inevitably deprive the Region and individual countries in the Region from driving their own research agenda and deciding about their own priorities, if this international agenda is not complemented and balanced by local funding and investment. It is our inner conviction that rather than resisting international collaborations, the best way for the Region to influence the local and international agenda is to scale up its participation to the international enterprise of knowledge production. Investing in clinical research and building capacity of good quality clinical research should go hand in hand with developing international standards Regional and National clinical research regulations. These latter should not be set only with the purpose of regulating access to the Region of products and clinical trials from high income countries. Actually, most of the WHO “essential medications” are generic or soon to become generic drugs, and/or produced in the Region. Clinical trials of treatments strategies using such drugs, or soon to be available biosimilars as well as bioequivalence, safety, clinical effectiveness and other trials are essential to fund and to develop locally with the ultimate aim of benefiting patients in the Region.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite a significant progress over the last two decades, the MEMA region contributes little to the international effort of health knowledge production. Despite many weaknesses of clinical research in MEMA, the Region has a number of attractive features and progress is being made toward higher standards of human subjects’ protection, adequate functioning of ethics review systems, streamlined authorisation timelines, and contained bureaucracy.

An international multi-stakeholder effort may act synergistically towards harmonising the regulatory framework and designing a roadmap for sustainable capacity building in the region, enabling it to produce its own health knowledge and to efficiently join the global knowledge production enterprise.

One further element to be taken into account is the emergence of new countries in Asia, competing for recruitment of study subjects, predominantly in densely populated countries such as India, China, Indonesia, Japan, Thailand and Malaysia. Most of these countries are facing similar issues highlighted here for the MEMA countries and struggling in various ways to reform their local regulatory framework.8,41–44 Difficulties in the planning and implementation of effective health care in most African countries are compounded by a paucity of studies and a low rate of investment in research and data acquisition.40

Most of clinical research in the Region is funded by companies and led by investigators from high income western countries. This would inevitably deprive the Region and individual countries in the Region from driving their own research agenda and deciding about their own priorities, if this international agenda is not complemented and balanced by local funding and investment. It is our inner conviction that rather than resisting international collaborations, the best way for the Region to influence the local and international agenda is to scale up its participation to the international enterprise of knowledge production. Investing in clinical research and building capacity of good quality clinical research should go hand in hand with developing international standards Regional and National clinical research regulations. These latter should not be set only with the purpose of regulating access to the Region of products and clinical trials from high income countries. Actually, most of the WHO “essential medications” are generic or soon to become generic drugs, and/or produced in the Region. Clinical trials of treatments strategies using such drugs, or soon to be available biosimilars as well as bioequivalence, safety, clinical effectiveness and other trials are essential to fund and to develop locally with the ultimate aim of benefiting patients in the Region.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite a significant progress over the last two decades, the MEMA region contributes little to the international effort of health knowledge production. Despite many weaknesses of clinical research in MEMA, the Region has a number of attractive features and progress is being made toward higher standards of human subjects’ protection, adequate functioning of ethics review systems, streamlined authorisation timelines, and contained bureaucracy.

An international multi-stakeholder effort may act synergistically towards harmonising the regulatory framework and designing a roadmap for sustainable capacity building in the region, enabling it to produce its own health knowledge and to efficiently join the global knowledge production enterprise.

One further element to be taken into account is the emergence of new countries in Asia, competing for recruitment of study subjects, predominantly in densely populated countries such as India, China, Indonesia, Japan, Thailand and Malaysia. Most of these countries are facing similar issues highlighted here for the MEMA countries and struggling in various ways to reform their local regulatory framework.8

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the contribution of the following for their input at the CVCT MEMA regulatory summit: Hala Adly (Cairo, Egypt), Muna Al- Mahmoud (Amman, Jordan), Mouez Ben Ali (Novartis, France), Hazem Dessouky (Novartis, Egypt), Nihal El Habashy (Alexandria; Egypt), Ashraf El Kouly (Pfizer, Egypt), Mohamed Hsairi (Tunis, Tunisia), Ines Khochtali (Monastir, Tunisia), Michael Nabil (Sanofi, Egypt), Harun Otieno (Nairobi, Kenya), Gehan Ramadan (Novartis, Egypt), Amr Saad (Cairo, Egypt), Nancy Sayed Awad (IQVIA, Egypt).

Funding

CVCT MEMA regulatory summit workshop, Cairo, September 13th- 14th 2018 was funded by educational grants from pharmaceutical companies and Contract Research Organizations.

Authorship contributions

All authors participated to the CVCT MEMA regulatory summit workshop, Cairo, September 13th- 14th 2018, except JB, RM and KS. FZ drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed providing critical review and edits and have approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors have completed the Unified Competing interests form from http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available upon request from the corresponding author), and declare no conflicts of interest.44