Critical illness in resource-limited countries (RLCs) remains a crucial determinant of all-cause mortality and health outcomes. 1 The lack of skilled and available emergent and critical care leads to an unacceptably high number of potentially preventable deaths, especially in acutely ill pediatric patients with curable illnesses. 2,3 In particular, access to tertiary care centers is important for the sickest patients; however, this care is typically limited to central urban areas and more widely available primary and secondary facilities lack the necessary resources to treat the severely ill. 4,5

Our knowledge on emergent and critical care access in RLCs remains rudimentary. Known factors that result in more severe patient presentations upon admission at a tertiary care center include low to no medical accessibility, poor recognition of illness, and care in an under-skilled intensive care unit (ICU) 3,6,7; however, linkages between these factors and patient severity as well as outcome data remain obfuscated. Indeed, a major barrier to quality critical care in RLCs has been the scarcity of epidemiologic data - including patient demographics, understanding of basic medical infrastructure, and outcome data. 6,8

The effect of geographic distance on access to emergent and higher level care in RLCs has been proposed as an important determinant of patient severity and outcome. 9 Seeking care at higher-level facilities may involve long distances travelled, further exacerbated by referrals, and may impact the decision to seek care and the severity of patient presentation and outcome. For example, distance to care has been positively associated with maternal and newborn mortality. 10 Even in resource-abundant countries, distance travelled to emergent care is associated with worse outcome and may impact the decision to seek or complete medical care. 11,12 Importantly, the greatest association between poor outcome and distance travelled was seen in patients with respiratory conditions 11 – which represents the majority of acutely ill patients in RLCs. 13 As such, distance travelled is critical to evaluate in RLCs, given the current gap of knowledge on how distance affects care-seeking behavior and outcomes.

A simplistic application of critical care principles in resource-abundant countries, where the cost of care is exorbitant for any one individual, to RLCs is not sufficient and may even be harmful to RLCs 6,14; therefore, context-specific analyses within existing emergent and critical care systems in RLCs is warranted to better understand avenues for improvement. However, before improvements in the emergent and critical care system in a RLC can be proposed, the system and its population need to be well-understood. For our study, we focused on Vietnam, a RLC where sharp divides in access to emergent medical care and child mortality persist among socioeconomic classes, age groups, and ethnic backgrounds. 15–17

In Vietnam, access to care is hierarchical and centralized. Tertiary pediatric care is available in three major cities: Hanoi, Da Nang and Ho Chi Minh. This availability affects patients from remote areas - comprised of mostly lower socioeconomic classes – who face lengthy travel in addition to a cumbersome referral process if they seek care. 18 Patients often enter the medical system at low- and mid-level facilities due to proximity as well as Vietnam’s “gatekeeper referral system” - where care is initially sought at lower levels to prevent overcrowding at high-level hospitals – although emergent care may be sought anywhere. 19 Importantly, all referrals enter the Emergency Department (ED) before admission to an ICU. Conditions referred to higher level care include infectious diseases, prematurity complications, and respiratory distress. 5 It is unclear whether Vietnam’s referral systems contribute to negative health outcomes or increase access to care by preventing overcrowding.

While Vietnam has reduced child mortality and improved access to pediatric care through nationwide efforts and insurance programs 15,19–25, the under 5 years old and pediatric ICU mortality rates remain high compared to those rates in resource abundant countries. 3,23 While past studies have identified vulnerable Vietnamese pediatric patient populations, geographic locations and exacerbating factors contributing to these populations’ severe conditions and health outcomes have not been not evaluated. Improvement of children’s health in these vulnerable populations warrants examination of the severity of illness when care is sought, referral pattern, and distance traveled to seek care. A focus on how high-level, emergent pediatric care is accessed will help to understand how the current systems function, identify at-risk populations, and ultimately aid in potential interventions or improvements to serve Vietnamese and other RLCs’ pediatric populations.

METHODS

This study was a single center prospective observational study conducted at Vietnam National Children’s Hospital (VNCH) in Hanoi, Vietnam, the largest tertiary referral center in Northern Vietnam. Any patient under 18 years of age who was examined in the emergency department, then admitted to an intensive care unit was eligible. For ethical reasons, we excluded patients who died or were imminently dying on ED admission prior to transfer to intensive care as well as their caregivers. This study was conducted during a 5-month period from July 2018 to December 2018. We enrolled 471 patients, 15 of whom were excluded for missing medical admission data.

Survey

Interviewers were trained in informed consent, study processes, and interviewing techniques. Informed consent was received from the accompanying parent or caregiver. Surveys were completed by either a self-administered by a written form or orally administered by a trained interviewer. The survey included questions regarding socioeconomic demographics, care seeking behaviors, numbers of lower level facilities visited, referrals from lower level facilities, mode of transportation, insurance, and travel costs.

Admission and outcome

When seen in the emergency department, patient acuity was assigned an Emergency Severity Index (ESI) score in guidance with the ESI v4 Algorithm, a validated tool for assessing patient status in pediatric critical care 26, independently by two trained ED staff (nurse or doctor) or pediatrics resident physician. ESI score ranged from 1 (requiring immediate life-saving treatment; e.g. compromised airway, unresponsive, or hemodynamic instability requiring emergent pharmacy), 2 (high-risk situation, unstable vitals), 3 (need for multiple interventions; e.g. imaging studies, intravenous fluid, labs), 4 (one intervention needed), to 5 (no interventions needed). Patients’ past medical history, outcome of admission, and disposition after discharge were ascertained from the medical record. Outcomes were recorded as regular admission (<60 days), extended admission (>60 days), or expiration in the ICU, and were followed up to sixty days following admission. Outcome data was collected on 383 patients.

Data measures

Variables were dummy coded categorically except for the following numerical variables: age, family members, length of stay, delay in care-seeking, time to closest medical facility, number of facilities visited before VNCH, and transport time to VNCH.

For logistic regression analysis, the main dependent variables (outcomes) assigned were either an ESI=1 (vs ESI >1), an outcome of extended admission/expiration in the ICU (vs. discharge within 60 days), an answer “Yes” to a variable impacting the decision to seek care (vs. “No”), or a distance greater than 60 km to VNCH (vs <60 km). Independent variables (risk factors) were placed in binary categories. Bivariate analysis was completed using the Baptista-Pike method to calculate an odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval and a two-tailed Fisher’s exact test to calculate a specific P value.

Our numerical data of days delayed to care or to VNCH was found to be significantly nonparametric by multiple normality tests (D’Agostino & Pearson, Shapiro-Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnov); we therefore employed log-rank analyses in our comparisons between risk factors. For most analysis, we divided the risk factor into binary categorizations and tested for significance using Mann-Whitney tests and approximate P values. When distance to VNCH was divided into multiple groups, we assessed for significant differences using one way ordinary ANOVA with Dunnett’s corrections for multiple comparisons.

All data analysis was performed on GraphPad Prism 8.0 Software (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA, USA).

Ethics

Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, USA and Vietnam National Hospital of Pediatrics in Hanoi, Vietnam.

RESULTS

Demographic and admission data

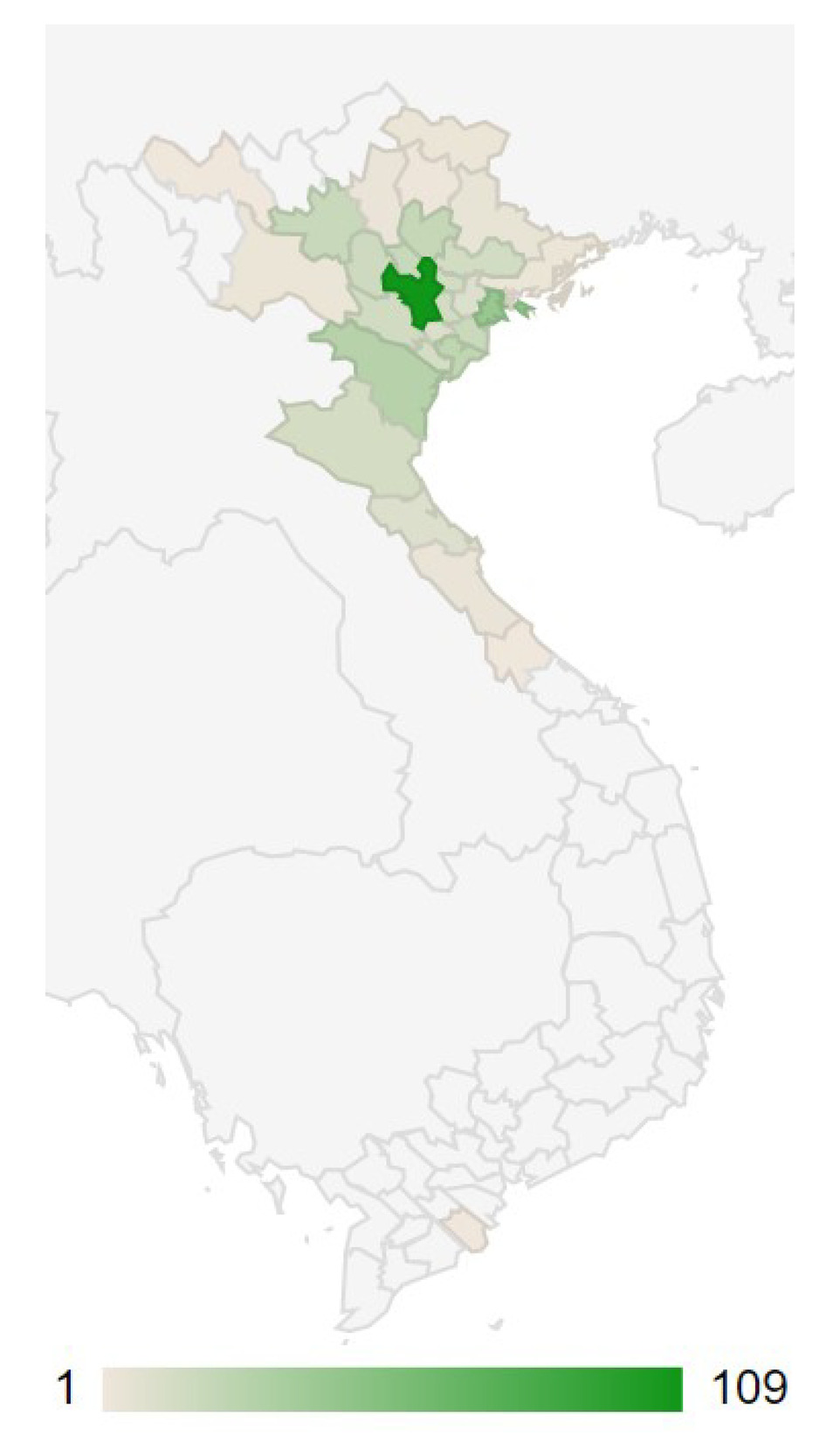

Our sample contained 456 pediatric patients from provinces in northern Vietnam admitted to an ICU from the VNCH ED (Fig 1, Supplementary Table 1). Demographic data are reported in Table 1. Patients sampled had a median age of 1.8 months, with 83.3% under 12 months old, and were predominantly Kinh, or Vietnamese ethnic majority (91.4%), residing in a rural location (64.3%).

On admission, infectious disease was the most common diagnosis (64.3%), of which pneumonia and encephalitis prevailed (Table S2 in the Online Supplementary Document). Diagnoses were not mutually exclusive and cardiovascular and prematurity diagnoses were also prevalent. Consistent with the age range and admission diagnoses of our sample, admission to the medical ICU was the highest followed by the neonatal ICU (Table 2). Before ICU admission, patient acuity was scored with the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) V4 algorithm, most patients presented with an ESI=1 (40.5%), requiring life-saving interventions, or an ESI=2 (48.5%), requiring multiple emergent interventions. 390 patients were followed in the ICU and outcome data, including length of stay, was collected.

As VNCH is a major tertiary referral center and patients may have sought care elsewhere, we assessed distance to care and referrals (Table 3). Most patients were within 10 km to the closest medical facility from their residence (88.9%); however, in contrast, the most patients were further than 60 km to VNCH (66.1%). We next analyzed if distance to VNCH related to the duration of travel patients and their families underwent, and found longer distances took greater travel time (Supplementary Figure 1). If VNCH was not the first facility visited, then the median number of care centers visited was one (57.5%). The time between the first facility visited and VNCH admission was widely distributed, with most patients being sent to VNCH within 24 hours (54.3%).

Caretaker survey data

The impact of distance and insurance status on care-seeking behavior was analyzed (Table 4). Most patients were covered under government or public health insurance (89.1%). 33.1% of caregivers responded the presence of health care coverage impacted their decision to seek medical care for their child. In regards to distance, 20.9% and 34.9% of caretakers answered the proximity to the closest medical facility or to VNCH, respectively, impacted the decision to seek care. Ambulance was the main mode of transport to VNCH (73.7%); however, only in 40.6% of cases were transportation costs covered by insurance. Importantly, 94.2% of parents were missing work unpaid to be at VNCH. Caretaker delay to care, the time between recognition of the child’s acute illness and the pursuit of care outside the home, had a median of 0 days, with an average of 1.68 days.

Acuity on admission relationships

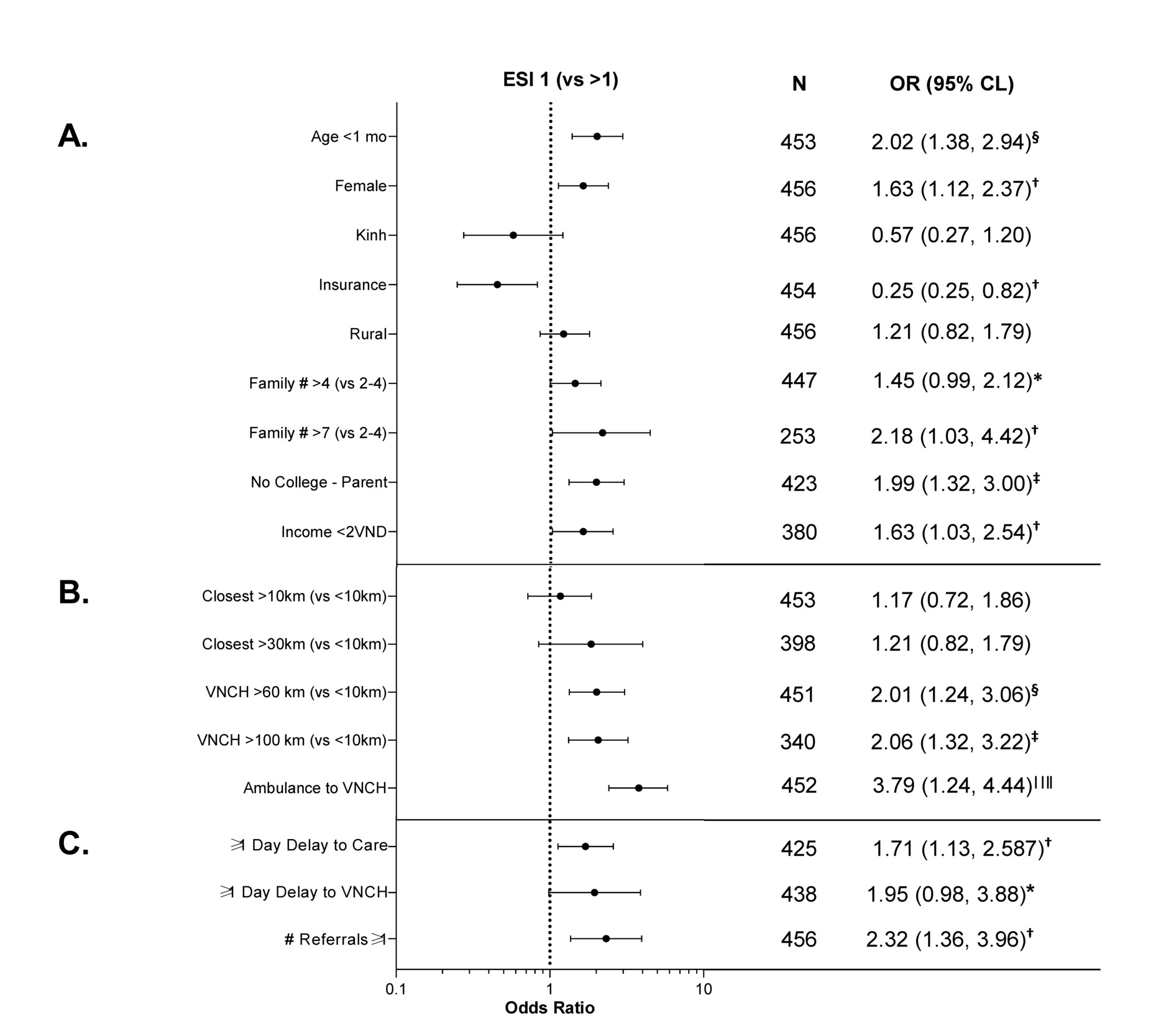

Multivariate analysis was performed to examine factors that increased the odds of an admission with the highest acuity ESI score of 1 (Figure 2). The following demographic variables were associated with an ESI=1: age under one month, female sex, family size >4 members or >7 members, parental lack of college education, and family income under 2 million VND per family member (Figure 2, Panel A). Importantly, insured patients were less likely to present with an ESI=1 on admission.

Given the diversity in distances traveled, we examined the relationship of distance to medical facilities to acuity on admission (Fig 2, panel B). Distances to the closest medical facility greater than 10 km or 30 km were not associated with a higher acuity on arrival; however, distances to VNCH greater than 60 km were significantly associated with increased acuity on admission. Patients who arrived via ambulance to VNCH had a more severe acuity on arrival as well. Additionally, we examined the duration of travel to VNCH and found patients whose travel went over 60 mins were more likely to have a severe acuity on admission (Figure S2 in the Online Supplementary Document).Patient admission acuity was also related to care-seeking behavior (Figure 2, Panel C); patients who experienced at least 1 day delay to care or to VNCH had a higher acuity on arrival. Additionally, patients who were referred at least once, and thus transferred hospitals at least once, presented with a higher acuity on arrival.

Outcome Data in the ICU

Bivariate analysis was expanded to analyze factors affecting outcome data with odds ratios reported as the odds of an outcome of an extended stay or expiration in the ICU vs. an ICU discharge (Figure 3). We first compared admission acuity with outcome data as the ESI is a widely used tool with well-known construct validity in both adult and pediatric populations. 26,27 Consistent with a more severe admission acuity, patients with an ESI=1 on admission were more likely to have a worse outcome (Figure 3, Panel A); however, the only demographic data associated with a more severe outcome were parental lack of college education and family income under 2 million Vietnamese Dong (VND) per family member (Figure 3, Panel B). Regarding travel, more severe outcomes were associated with a further distance from home residence to both the closest medical facility and to VNCH (Figure 3, Panel C). Consistent with admission acuity, patients who rode in ambulance to VNCH, experienced at least 1 day delay to any care or to VNCH, and who were referred at least once were more likely to have a more severe outcome (Figure 3, Panels C-D).

Determinants of Care-Seeking:

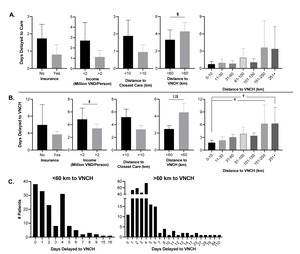

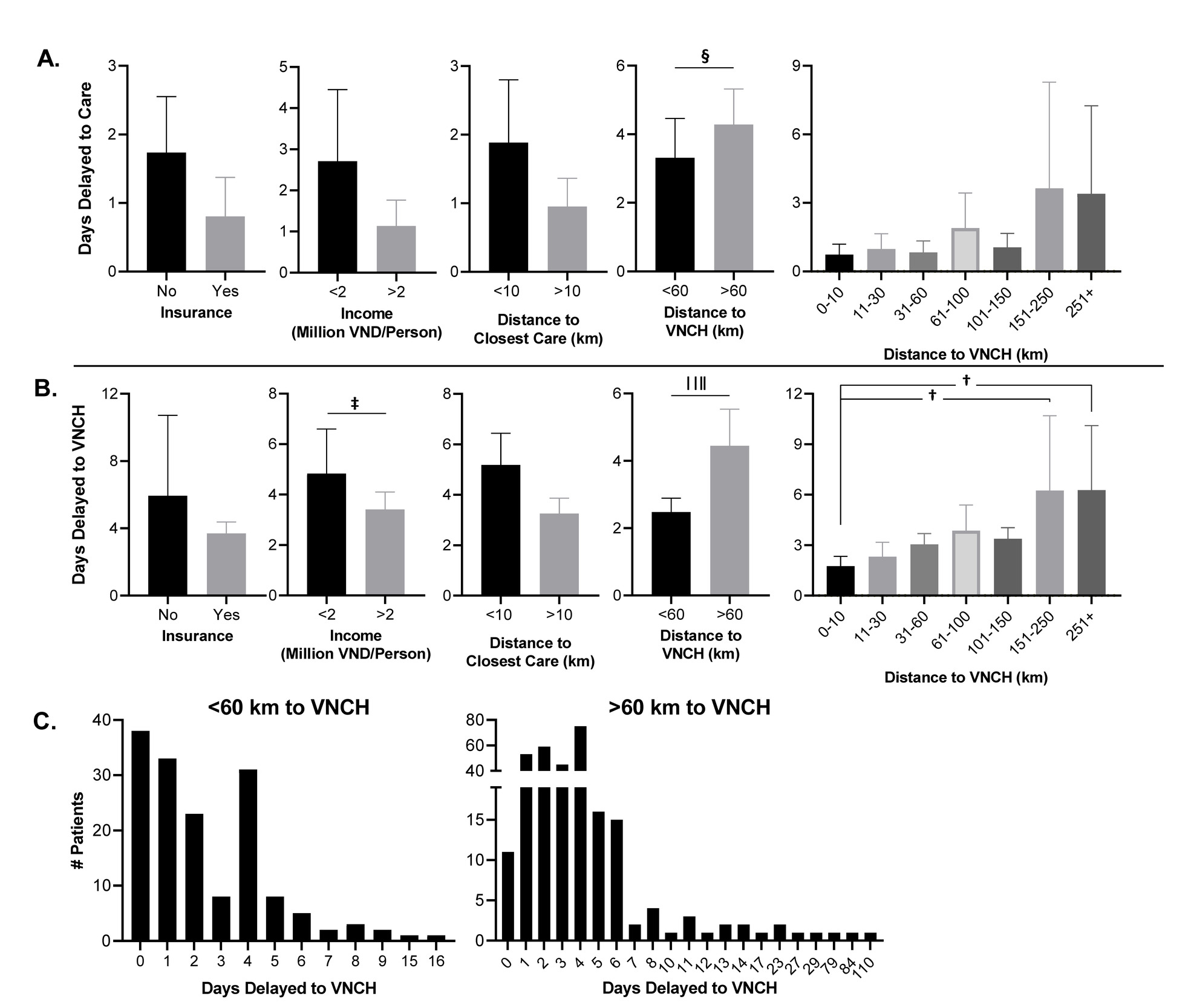

Given the significant association between days delayed to care or VNCH and admission acuity and outcomes, we sought to analyze the factors affecting days delayed care-seeking (Figure 4). Intriguingly, increased days delayed care-seeking were associated only with an increased distance to VNCH over 60 km (Fig 4, panel A); however, when days delayed to VNCH (=days delayed to care + time between first facility and VNCH) was calculated, it was positively associated with a greater distance to VNCH and an income lower than 2 million VND per family member (Fig 4, panel B). To understand the range of days delayed to VNCH, histograms for patients fewer than 60 km and over 60 km to VNCH were plotted (Fig 4, panel C). Strikingly, the patients within 60 km to VNCH were within 16 days from onset of illness to VNCH admission whereas patients over 60 km exhibited a right-shift with days delayed to VNCH up to 110.

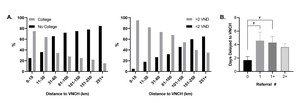

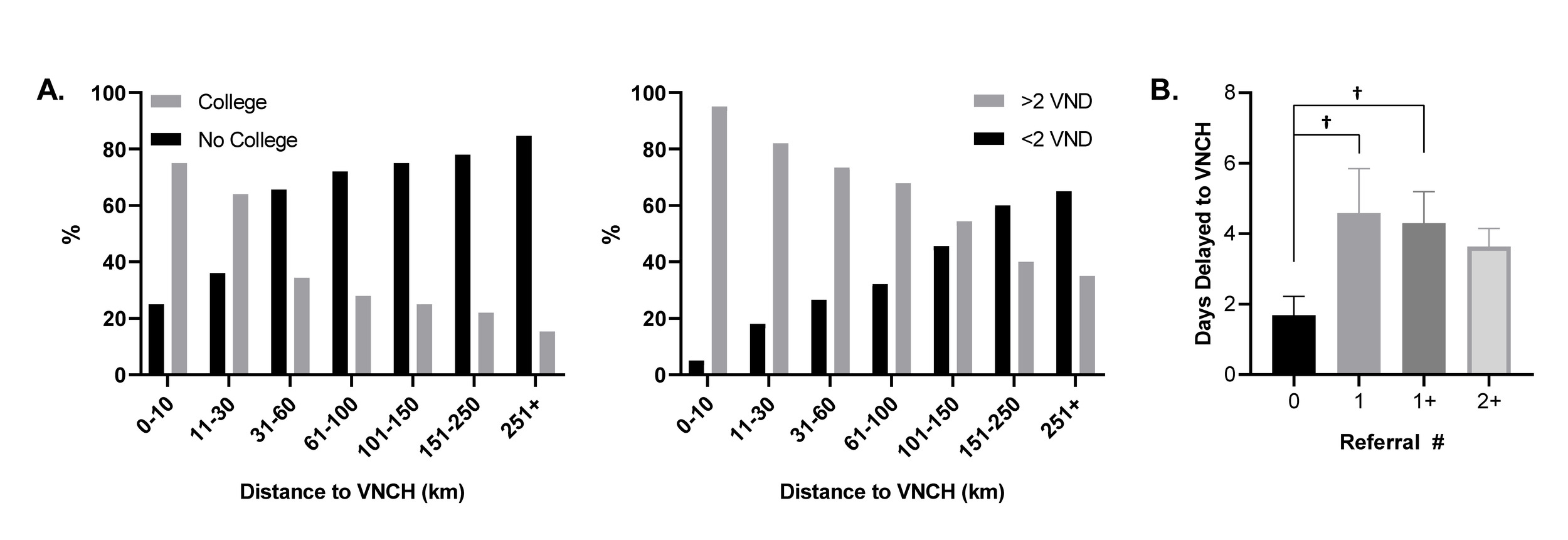

We next asked parents about factors that influenced their decisions to seek care and found (Fig 5, panel A): a distance greater than 10 km to the closest medical facility was more likely to affect the parent’s decision to seek care at that facility, a distance greater than 60 km to VNCH was more likely to affect the parent’s decision to seek care at VNCH, and patient insurance coverage was more likely to affect the parent’s decision to seek medical care. A visualization of these impacts on the decision to seek care is shown as percentages per group in Supplementary Figure 3.

As distance to VNCH greater than 60 km was associated with impacting the decision to seek care in addition to multiple metrics (outcome, days delayed), we sought to further analyze this population. We found it was associated with caregiver income less than 2 million VND per family member and lack of college education, as well as a greater number of patient referrals (Fig 5, panel B). These data are graphed in Figure 6 and show the near linear relationship between lack of college education and decreased household income to greater distances from VNCH. In addition, we found patient referrals of 1 or greater than 1 are associated with an increased number of days delayed to VNCH.

DISCUSSION

The role of distance to care

Our study focuses on emergent cases requiring critical care in northern Vietnam and highlights the effect of distance travelled to a tertiary care center on patient admission and outcome. Importantly, a greater distance to VNCH was associated with a greater number of days delayed to care and to admission at VNCH – which were independent predictors of a severe admission acuity and outcome. Indeed, the caretaker’s decision to seek tertiary care was more likely to be impacted the further the patient was from VNCH – in particular, those children over 150 km were most delayed. The cost of seeking care likely delays care-seeking as those further away incurred more expenses at the cost of greater time away from work unpaid and personal travel costs to VNCH as over 50% of caretaker’s self-paid expenses to VNCH. Additionally, patient households in provinces further away from VNCH are more likely to be in lower income brackets, which may constrain caretaker’s decisions as we found that a lower income was associated with delaying care-seeking.

It is important to note that many variables (mode of transport, traffic congestion, availability of transport) likely affect the decision to seek care and the journey to tertiary care. In our study, we focused on distance to care, which was related to the duration of travel, because we believe it is a crucially important determinant in care-seeking behavior and health outcomes.

Factors in health outcomes

The nature of the referral process and transfers compounds patient acuity and outcome. Our data indicate that any referrals led to worse acuities and outcomes – potentially from care received within the lower and middle level facilities, which lack the standardized protocols, training, and staff to adequately deal with critically ill patients. 5,6,8 Another risk factor is the transportation process itself. Resources in an ambulance are often insufficient and severely sick patients, especially those in respiratory and neurological distress as in our patient population, fare worse with increasing travel. 28,29

The discrepancies in health acuity and outcomes we observed in lower income and distanced patients may partly be explained by the fact 30% of insured patients pay out-of-pocket to bypass the referral process and seek higher-level care directly. 15 Additionally, recognition of initial illness can contribute to this aforementioned gap – as poor caretakers are less likely to have higher education and recognize early warning signs to seek care. 30–34 Consistently, in our study, we observed worse health acuity and outcomes for children whose caretakers did not receive a college education or were disproportionately located in provinces further from VNCH.

These findings on income and education on patient acuity are in line with a previous study in VNCH that examined all patients entering the ED 7; however, there are important distinctions – our study focuses on patients requiring critical care only and also gathers outcome data to sixty days. More longitudinal outcome data in particular is important given its paucity in LRC research and critical care studies. As most of the patients in our study were severely ill, requiring life-saving treatment often, we felt it was important to follow the outcomes to adequately identify discrepancies between groups.

Future directions

Ensuing research needs to take into account the at-risk, critically ill patient populations in need of skilled tertiary care at the primary and secondary centers as well as in remote communities. It is possible that children capable of the journey to VNCH are privileged in contrast to those children unable to make the journey and we are missing those groups who are most at risk. Additionally, a further expansion of our project to other skilled pediatric tertiary care centers in Vietnam or in other LRCs in Southeast Asia would greatly benefit the strength of our findings and the utility of our research for the global health field.

Given that facility distance impacts utilization of care and child mortality in resource-limited environments 35, resources and expertise should be divided strategically to maximize the health of the pediatric populations. In Vietnam, this allocation could involve standardizing care protocols amongst primary and secondary facilities further than 150 km from tertiary care centers for prevalent conditions such as pneumonia, sepsis, neonatal respiratory distress syndrome and congenital heart disease. Quality care with less expense could be strengthened through nurse training on the recognition of danger vitals and instituting algorithms under the focus of essential emergency and critical care. 1,3,36 Additionally, public health education efforts to these remote provinces could aid the early recognition of child illness by their caretakers and improve health outcomes. 37

Limitations

In our sample, we were unable to assess cases from different geographic distances that required the resources of VNCH, but could not come to VNCH either from an income standpoint or from a medical standpoint. These patients represent key demographic populations at risk and their omission introduces bias into our analysis; however, their data retrieval would be incredibly complex from multiple primary and secondary care centers. We also did not survey patients who were at risk of imminent mortality upon admission, and may represent an important population to analyze socio-demographic differences, for ethical reasons. We may also require more outcome data to determine precise ORs for the risk factors of >1 days delayed to care/VNCH and >1 patient referrals because in these specific cases we only had 2-3 patients discharged. Thus, the calculated ORs and 95% CLs are large albeit significant.

An additional limitation is that we did not ascertain the valence of factors that impacted caregiver’s decision to seek care (positively/negatively impacted the decision) and can only hypothesize that insurance was a positive influence to seek care whereas further distances to care or to VNCH was a negative influence. Medical records, while electronic in the ED, were paper-form in the ICU – which complicated the recording and contributed to loss of follow-up of patient outcomes. Lastly, given the northern location and time frame, results of our study may not extend to all of Vietnam.

CONCLUSIONS

Our data indicate a clear need to improve and better mobilize resources for those disproportionately affected children and their caretakers who live long distances from tertiary care centers and are therefore at-risk of worse health outcomes and delayed care-seeking behavior.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Vietnam National Children’s Hospital for their excellence in making this study possible. We thank Dyda Dao for critical insights regarding statistical testing. We declare no competing interests.

Ethics Approval: This study received ethics approval at both Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota and Vietnam National Children’s Hospital.

Funding: There was no direct funding for this research.

Authorship Contributions: DR, TX and YO conceived and oversaw all components of the project. DR, TX, VH, KT, TP, and DL generated the survey components and data retrieval. DR, TX, SK performed data entry and data analysis. DR, TX, and YO wrote the paper.

Competing Interests: The authors completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available upon request from the corresponding author), and declare no conflicts of interest.

Correspondence to:

Yves Ouellette, MD-PhD

Consultant, Mayo Clinic

Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine

Division of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine

2001st St SW

Rochester, MN55905

USA

[email protected]

David A Rollins, PhD

Mayo Clinic

Alix School of Medicine M3

2001st St SW

Rochester, MN55905

USA

[email protected]