Maternal health is of great importance in all societies. It is defined by the WHO as “the health of women during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period (42 days post-delivery)”.1 This study examines the situation in Nepal, a small country in the Himalayas with a population of around 27 million, where maternal mortality was shown to be still one of the biggest public health issues, with one woman dying every four hours in 2016.2

Significant progress has been made in the last two decades regarding the Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR). This improvement was stimulated by Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 5, which aimed to reduce MMR.3 Safe Motherhood and newborn health programmes and policies were prioritised to increase the availability, access and utilization of maternal health services, including safe abortion.4 They contributed to a decrease in the MMR in Nepal from above 900 in 1990 to 258 in 2015.5

Despite the progress that has been made, the mean MMR of 258 is still high. This is due to several contextual factors that limit access to and use of maternal health services, such as challenging geographical terrain, underdeveloped transportation and communication systems, poverty, illiteracy and women’s low status in society.6 Women from rural and socio-economically marginalized castes and ethnic groups are mainly affected by such factors,7,8 reflecting inequities in maternal health.9 Health inequities are the result of the exclusion of marginalized groups within health systems in terms of a lack of voice to improve access and financing for health services. These inequities can be addressed through group participation and the health system’s accountability.9 Citizen participation in the assessment and planning of health services is more likely to lead to addressing their needs and to improving quality, access and use of the services.10 In this study we explored the participation of stakeholders in structures and activities implemented by the government or NGOs as a social accountability approach to ensure maternal health sector accountability to all communities, including remote areas.

Theoretical framework

Social accountability refers to the mechanisms which increase people’s ability to voice their concerns and needs and claim their rights.11 Information, dialogue and negotiation are key concepts within social accountability, which facilitate change and engagement among actors.11,12 Considering the first concept, “information”, health providers have better knowledge about health care than patients, so patients rely on them to provide information regarding services and treatment options.12 Citizens cannot demand services and claim rights if they do not know what they are entitled to. The provision of health information will lead to knowledge about standards and thus generate a demand amongst citizens regarding their rights to better health care services.11 Information alone might lead to awareness of gaps in the health services but not necessarily to the desired improvement. After the knowledge has been acquired and complaints/concerns collected and compiled, the “dialogue & negotiation” concepts engage citizens in the community and health providers to acknowledge the complaints and reflect jointly on solutions for mitigation. The overall goal of “dialogue & negotiation” lies in the formal accountability chain by sensitising health providers and policy makers to the rights and needs of citizens, in this case women, and encouraging them to take up their formal responsibilities in order to ensure the women’s demands are heard and addressed.11

Papp et al. observed that in India, the information, dialogue & negotiation accountability model enables gaps in the formal hierarchical and informal community feedback loops to be identified, and thus the formulation of actions to create improvement, which is able to support even marginalised groups in confronting relationships with actors who possibly disempower them.11

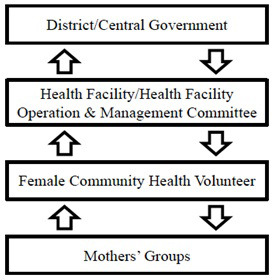

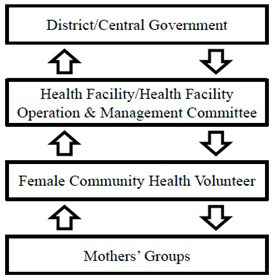

Social accountability has different ways of analysing and optimising the quality of health services and providers. In fact, the manner in which social accountability mechanisms function can be viewed as a feedback loop. First of all, social accountability involves people at the grassroots level, in this case women, voicing their needs and concerns and claiming their rights regarding health care. These voices need to be heard by agencies at higher levels, such as health providers or governmental authorities. Subsequently, a response that deals with the issue will be communicated to the community level to complete the feedback.12 Figure 1 shows the structures and the feedback loops specifically for Nepal.

If the feedback loop is lacking, for example regarding the responsiveness of the health care providers, women may feel they are not being heard or treated in a respectful manner and will be unlikely to continue voicing their issues or seek care at the health facilities in the future. As a result, the formal chain of accountability is dysfunctional. It is important to understand that it is mainly the poorer people, eg, in rural areas or slums, who feel the effects of this, as the wealthier people have the funds and resources to seek a higher quality of care.12 Adequate social accountability mechanisms can empower affected people through the provision of knowledge regarding health care services and their rights to receive quality care. Social accountability mechanisms can also enable like-minded people to unite in their opinions, which ultimately strengthens their voice.

Social accountability structures in Nepal

Interventions in Nepal to improve service responsiveness through social accountability originate mainly from Mothers’ Groups for Health, commonly known as Mothers’ Groups. The original Mothers’ Group is one of the oldest civil society groups in Nepal’s history,13 dating back to the 19th century. They are open to all interested women of reproductive age.14 NGOs and INGOs have helped these groups develop their network since the establishment of democracy in Nepal in 1990. Some of their activities related to maternal health are: facilitating community health workers to implement maternal and child health programs, and establishing savings and credit schemes to improve the overall economic situation of women (and their households).15

Another structure of importance for holding service providers accountable consists of Female Community Health Volunteers (FCHVs). FCHVs were originally introduced under the Public Health Division of the Ministry of Health of the Government of Nepal in 1988 and are now present in every Nepali district, with a total of 48,549 volunteers.16 Their activities include assisting during primary health care activities by providing health education and counselling on maternal care, essential newborn care, immunizations, family planning, and acting as a bridge between the government health services and the community.17

The third structure in Nepal that has a role in accountability is the Health Facility Operation and Management Committee (HFOMC), as it is responsible for overseeing the management of the health facilities present in the communities. HFOMC is a committee of citizens and a chair who is a governmental official and manages the health facility. The HFOMC’s main roles are health service management and monitoring. It monitors the health facility and the healthcare provided to the community, mostly through monthly meetings. If monitoring reveals an issue, the HFOMC will attempt to solve it itself, or inform the district government level. Besides their monitoring role, they also fulfil an informal role as a disseminator of information regarding campaigns and programmes on maternal health. The goal of the HFOMC is to give the local community a voice in managing their health facilities and health programs at the community level.17

Prior to the launch of the three-year Program for Accountability in Nepal (PRAN, 2010-2013), an evaluation report containing recommendations for the focus points in the PRAN programme was published under the supervision of the World Bank. Regarding social accountability, the report identified the citizens’ lack of essential information about their entitlements to participate in the formally established committees, and thus the absence of meaningful interaction with the state actors to optimise community services, and of trust in these bodies.18

In our study, conducted 10 years after the recommendations of the previous studies and four years after the PRAN program, but just before the elections of 2017, we investigated the role of social accountability mechanisms in maternal health and challenges regarding these mechanisms in Baglung district, Nepal, as part of a wider program to analyse differences between Nepal and India.

METHODS

Study design

We conducted a qualitative study as this enabled us to explore and describe existing social accountability mechanisms as experienced by the relevant stakeholders, i.e. structures, tools, activities, etc., regarding the three key concepts of the social accountability framework - information, dialogue & negotiation. Ten semi-structured interviews were conducted and four focus group discussions (FGDs) were held with participants from the community, healthcare providers and healthcare officials at the district level.

Study setting

This study was conducted in the Baglung district, selected deliberately because of i) limited access to maternal health services in terms of remoteness, high proportion of poor and disadvantaged groups, and poor level of women’s empowerment19 and ii) feasibility of the study in terms of ease of data collection. Baglung is a rural district situated in the mid-hills with a population of about 270,000. The centre of the district is connected to Nepal’s second biggest city, Pokhara. As a result, the communities in central Baglung are well connected to health services. This is not the case for communities living in the more rural areas of the district.20 Research carried out in Baglung in 2012 showed that the delay in deciding to seek care by pregnant women in the district occurs mostly in families with low socio-economic status (SES), resulting in low decision-making power and leaving them unable to exercise their reproductive rights.20

Only 37.5% of women in three districts, including Baglung, reported being able to make decisions regarding their own health care.20 For the majority of women, the head of the family makes those decisions, either the men in the family or the mothers-in-law. However, the men in the Baglung district often work abroad, leaving the women to make decisions on their own or with their mothers-in-law. This study also demonstrates that even though women are not always the decision-makers, they had better knowledge than men about the maternal health danger signs (50% versus 25%).20 Additionally, women’s lack of trust in the healthcare system, the distance and transport involved influenced the utilisation of the maternal health services. Previous research recommended strengthening social accountability for maternal health and reinforcing women’s empowerment programmes, to enable women to make decisions regarding maternal care.11 We selected two Village Development Committees (VDCs – administrative sub-divisions of a district) in Baglung, which received several interventions on social accountability for maternal health: Amarbhumi and Hatiya. These two VDCs were selected due to feasibility to conduct interviews and travel.

Sampling and data collection methods

A purposive sampling method was used in consultation with the District Public Health Office (DPHO) and health facility managers to select and contact participants from two VDCs to ensure a holistic view of the current situation regarding social accountability mechanisms, and include participants with rich information whilst taking into account ease of data collection.21 The following interviews and focus group discussions were conducted: i) semi-structured interviews with four healthcare officials with a managerial role for maternal health service delivery; three healthcare providers or staff nurse/auxiliary nurse-midwife and FCHVs responsible for providing health care service at health facilities and communities, respectively; two I/NGO staff, and one mother on the community level; and ii) four FGDs with 7 pregnant and recent mothers, 12 healthcare providers and 18 HFOMC members. The data was collected using interview and FGD guides translated into the local language with the help of a local research assistant, specifically trained for study purposes, who also assisted with translation and interpretation during the data collection. The interviews and FGDs were audiotaped with prior consent from the participants.

Data analysis

The audio-recorded interviews and FGDs were transcribed and translated by the research assistant. The data was analysed by a thematic analysis approach. To allow systematic comparison between the participants, the texts were coded according to the two concepts (information and dialogue & negotiation) for the identified social accountability mechanisms. Data analysis was done using the qualitative analysis programme ATLAS.ti. Triangulation was applied to check for consistency of findings through responses from different sources to the same questions.22

Ethical approval

Scientific approval was granted by the Science Committee of the VU University Medical Center (VUmc) EMGO+ Institute in the Netherlands (EMGO WC2014-035 HZ). Ethical approval was received from the Nepal Health Research Council (NHCR) (Reg. no. 22/2016), which is a part of the Government of Nepal.

RESULTS

The results are presented according to the formal social accountability structures in the health sector, i.e. Mothers’ Groups, FCHV and HFOMC. Within each structure, we report on the current situation regarding information, dialogue & negotiation, followed by the gaps and challenges perceived by the informants. Lastly, the contextual challenges and perceived changes in maternal health outcomes over the last five years are presented. It is important to know that our informants mentioned various other information-dialogue-negotiation instruments, such as public hearings, radio, ward citizen forums, etc. As little information was available on these mechanisms, potentially due to their irregular use and the apparently limited participation in them, they are not included in the results.

Mothers’ groups

Information

Mothers’ Groups are groups of 25-30 women of reproductive age who meet every month. Health issues are discussed in these meetings. The women discuss their different views with each other, and also with the FCHV leading the discussion. FCHVs provide important information about health concerns and the need for antenatal care (ANC) and postnatal care (PNC) visits to the health centre and the services of health care facilities:

“In each ward we have formed a mothers’ group for health, and it meets once a month during which we as a FCHV lead the discussion. In the meeting we discuss different health-related topics.” [FCHV]

The mothers themselves also act as messengers of information further down the chain:

“I will learn about the services being provided by the health post. I will be able to share the problems as well as information to other mothers along with other people.” [Pregnant/recent mother]

Dialogue & negotiation

As mentioned, mothers are able to discuss the information provided, or raise issues and concerns regarding health services with the FCHVs in the Mothers’ Groups through dialogue (and eventually follow-up by negotiation with the health authorities). If an issue arises regarding the services during these meetings, FCHVs act as a bridge between the mothers and the healthcare providers and decision-makers at the district and central government levels. Mothers can also discuss issues directly with HFOMC members, healthcare providers (eg, midwives) and NGOs. Although FCHVs are the most common pathway to express any issues or concerns, these other actors can also act as a bridge since they are able to communicate their findings at the district and central government levels.

Gaps/challenges

First, the topics for discussion in Mothers’ Group meetings seem limited to providing information, mainly on health/medical-related topics rather than the quality of the services. Issues that the women raise with the FCHV and other members of the Mothers’ Group mainly concern physical or organisational issues when preparing for labour:

“Yes, they express their worries and concerns and in turn FCHVs counsel them regarding birth preparedness for example arranging money in advance, arranging vehicles in advance.” [FCHV]

According to a healthcare official, there may still be an issue of empowerment amongst the women in the sense that they do not feel comfortable discussing service-related issues with health staff or FCHV as they find this too personal. However, the women in Mothers’ Groups denied any possible issue with empowerment.

Second, there is currently no mechanism to monitor the Mothers’ Groups and collect information on their contents, number of participants and frequency:

“The Health Facility In-charge is supposed to monitor the Mothers’ Group meetings. But in reality there is no proper monitoring since there is no mechanism to report the activeness of Mothers’ Groups to the district.” [Healthcare official]

As a consequence, the district level is unaware of the actual number of existing Mothers’ Groups, and their functioning.

Third, there is also a lack of economic incentives (e.g. provision of snacks during the meetings) due to the cut in initial provisions, leading to variations in the women’s motivation to visit Mothers’ Groups according to weather conditions and other priorities in the rural farming cycle.

“At that time there was provision of allowance and snacks during the monthly meetings, but currently there is no such provision in our budget. Maybe that is why they have been discouraged a little. Maybe similar support is required in order to revive that activeness.” [FCHV]

Such incentives or snacks were recommended by the health providers, which were expected to encourage more women, especially in poor and remote households, to come to the meetings and to ANC/PNC. Women also suggested including fathers and other family members in the Mothers’ Group meetings to increase joint responsibility in decisions regarding pregnancy and risk signals.

Female Community Health Volunteer (FCHV)

Information

Most participants stated that FCHVs are important voluntary providers of health-related information to the community, either face to face, through household visits, or by telephoning. They often disseminate maternal health-related information during the Mothers’ Group meetings. A health-care official called them the messengers in the community:

“Basically, they (FCHVs) are the motivators at the community level. They provide health education and counselling.” [FCHV]

According to a healthcare official, FCHVs acquire information from the health facility during the FCHV’s monthly meeting with health facility staff, when pregnancies in the FCHV’s wards are discussed:

“…whatever technical message we have regarding the government policy and awareness, it will go down to the health facility who will pass it on to the FCHVs.” [Healthcare official]

According to the FCHVs, this mostly regards health-related information or information on new programmes, and not so much clear responses to previously communicated issues, complaints or needs.

The FCHVs then disseminate the information to the community during the Mothers’ Group meetings that they lead.

“After the meetings FCHVs go back to their working area and conduct Mothers’ Group meetings in which they disseminate the information …” [Healthcare provider]

Dialogue & negotiation

According to the healthcare providers and healthcare officials, if women have an issue or concern with the health services provided, they can voice these issues to the FCHVs, who can discuss the matter with health staff.

“If there are any complaints, then they can complain to the health post staff, and if they have any complaints regarding the staff, then they can tell the FCHVs.” [FCHV]

FCHVs in turn voice those concerns to the health post staff during the monthly meeting. As soon as the Health Facility In-charge is informed, (s)he will call a staff meeting to ensure the issue is solved. This is the theoretical situation when such a complaint occurs, as according to the interviewees (community members and health providers), there have been no health service-related complaints so far.

Another way for FCHVs to deal with issues or complaints made by the community is to refer them to the members of the HFOMC, as they manage the health facilities. FCHVs have stated they feel heard by the health facilities and the HFOMC members when it comes to voicing medical-related concerns raised by the community. However, some things are out of their hands here as well. In such a case, they often don’t get a response. This especially concerns budget-related issues.

Mothers can also directly voice their issues and concerns to the health facility staff instead of via FCHVs. However, according to one healthcare official, women feel more comfortable voicing their issues and concerns to FCHVs than to the health facility staff. The women prefer to discuss issues with family. Afterwards, if necessary, they or their family members will discuss it with the FCHV. Women explained that they only feel comfortable discussing health-related issues with the FCHVs; any other issue or concern with the services or system is perceived as too personal and will only be discussed with family.

Gaps/challenges

Several gaps and challenges were mentioned regarding the FCHV. One of the most important gaps is the fact that women at the community level do not discuss service-related issues and concerns with FCHVs. They solely discuss health-related or medical issues with them.

Second, the health management stated that the incentive for FCHVs to conduct Mothers’ Group meetings was terminated (i.e. allowance for provision of snacks during the meetings), which had a demotivating effect. It was evident that the regularity and frequency of meetings involving FCHVs have decreased.

So, the FCHVs recommended an increase in the previously provided incentive, as this would also increase their motivation to deliver good work.

“It would be better if there was an increase in the incentive for us FCHVs because we have to do a lot of work in the community during which our own personal work gets side-lined. So we would feel more motivated if there was an extra incentive for us.” [FCHV]

Third, FCHVs stated that nowadays people have become more literate, often more so than some FCHVs. As a result, they tend to undermine the FCHVs’ authority and don’t listen when they are told it is time for a check-up or any other maternal health-related message. This has previously resulted in people bypassing FCHVs and seeking specialised care when it is not necessary.

“In some wards people tried to bypass the FCHVs. In that case we went there and counselled people.” [FCHV]

Another challenge is that often people in the community believe FCHV is a paid job, which gives community members a negative perception of them. People feel the FCHVs act superior, which might be another reason to try to bypass them.

“We are volunteers, but people in the community think that we have a job and we earn money, so when we try to provide health education, some think we are acting high and mighty and know it all since we have a government job.” [FCHV]

Furthermore, people have high expectations of what FCHVs are entitled to do. For example, people demand medicines from FCHVs, which is not something they can provide. As a result, FCHVs have to deal with complaints from the community. In addition, no action is being taken by the HFOMC or at the district and central government levels to improve the positions of FCHVs, as FCHVs do not voice these challenges to the HFOMC.

“We just keep on working. Since we are volunteers and our first duty is to serve people, we do nothing about the complaints. We just continue working.” [FCHV]

A major challenge mentioned is related to geographic accessibility for people who live in remote areas. This forces FCHVs to travel long distances.

Health Facility Operation and Management Committee (HFOMC)

Information

If an issue arises amongst members of the community regarding the health services, the community can forward the complaint to members of the HFOMC in addition to FCHVs. This is said to occur regularly. However, these are not often health service-related issues. If members of the HFOMC are made aware of an issue, they will call an extra meeting to discuss and potentially solve it.

The HFOMC also hosts monthly meetings with FCHVs to ensure important topics are covered and to provide them with instructions.

Dialogue & negotiation

Once gaps or issues have been identified, they can be discussed in one or more meetings with fellow HFOMC members to find a solution. It is up to the members of the HFOMC to decide whether action needs to be taken. The chair of the HFOMC, who is a government official and often someone from outside the district, has the last word in this decision-making. If it has been decided that action needs to be taken, the HFOMC will either find a solution with its own resources, which is often the case, or if this is impossible, it will request the DPHO office or central government budget to provide funding for initiatives or negotiate an alternative solution for the issue. However, most of the interaction that takes place is not at the district and central levels. It is often between the HFOMC members and the health facility staff. Dialogue & negotiation with other health sector actors seem to be lacking.

The HFOMCs in both districts have realised some changes mainly through their own resources, eg, arranging land for a new health post, establishing a delivery centre, renovating the health post building, introducing water facilities and health education camps. Since the budget is controlled by the central government, the health facility or the HFOMC must report budget-related issues to the district level. Whenever this occurs, the district level informs the health services department, which decides on the solution to the issue. However, requests from HFOMCs but also from the district level are often not heard.

Gaps/challenges

A typical challenge is the difficulty of fundraising to improve the health system when no or just a limited budget is allocated by the central government level. But the most important social accountability gap is that the members of the HFOMC do not feel heard by the District Office.

“Sometimes the district doesn’t listen or address our demands. From time to time there is a shortage of medicine because of the irregular supply from district. Similarly, since the patient flow is very high, we requested an ultrasonography machine for this health post. But the district didn’t listen to our request.” [HFOMC member]

As a consequence, women who encounter complications during their pregnancy or during delivery are referred to the hospital in Baglung, which is several hours’ drive away. Women have previously said this makes them worried and anxious, yet nothing is or has been done in the Village Development Committee to enable attending to complications in the future.

Mothers’ Groups, FCHVs and HFOMCs were perceived as having contributed over the years to improved maternal health through increased awareness, more service-seeking behaviour, increase in service uptake, improved working circumstances for health staff, increasing and sustaining women’s empowerment, increased trust in the health facility, and a decrease in maternal deaths. However, this was not clearly documented in our study and needs further research.

Existing contextual challenges regarding maternal health

Respondents mentioned several persistent challenges to maternal health services at the study sites. The influences these factors have on maternal health cannot be addressed solely through social accountability.

Geographical access

A major challenge mentioned by many informants is geographical accessibility. Some people of the VDCs live in very remote areas, which makes it difficult for them to reach a health facility, or any other facility for that matter. The long distance decreases women’s motivation to go for all the check-ups during and after pregnancy. Women also struggle to estimate the right time to leave for an institutional delivery. In those cases women have to be carried over mountain pathways to the health facility on stretchers, which also has cost implications. Geographical conditions influence maternal health in other ways as well.

“Due to geographical barriers, mothers have to be carried to the health facility and for that the carriers have to be paid. Although the services in health facilities are free, the cost of bringing them to the health facility is high. That might act as a hindrance.” [Healthcare officials and similar statements by healthcare providers and FCHVs]

If the nearest health facility is far away, women rely on family members to take them there or manage the household, causing some women to depend on their family’s approval to seek services. This delay in seeking services could be caused by the family’s lack of knowledge of relevant health signals and the lack of women’s empowerment, according to a healthcare official.

A healthcare official described the lack of knowledge about the importance of modern maternal health care among mothers-in-law:

"The lack of knowledge and lack of understanding play a role in this issue. The mothers-in-law didn’t have access to such services, but they delivered normally, so they are like, why do you need all these services now?" [Healthcare official]

Health system gaps

The healthcare officials mentioned structural gaps in the maternal health care system in terms of a shortage of health staff and the gap between the knowledge and skills of health staff to act adequately.

They stated that initiatives often cannot be implemented due to a lack of funding. Such is the case with the maternal death review, which is regarded as an important accountability instrument at the district level, due to its ability to gather information, stimulate dialogue and prompt an adequate response to improve health services.

“Such a reporting mechanism is necessary because one VDC can learn from the incident that occurred in another VDC.” [Healthcare official]

Currently, if deaths occur in hospital due to complications, no official information will be sent to the VDC from which the individual came. If the death occurs on the way to the hospital, neither the hospital nor the VDC nor the health post will know about it and/or report it. The potential accountability loop is seriously hampered.

Women’s empowerment and voices

Several participants stated that the issue of empowerment is still difficult in the study sites. Some women struggle to raise their voice. However, the issue of empowerment, in the sense of more equal responsibilities between women and their husband and mother-in-law, is not as important in this district as many men are working abroad and sending money home to the family, leaving the women to organise the household with their mother-in-law if present, which makes them more independent.

“Yes, it’s still there (lack of empowerment), but this district is a little bit different. In this district most of the men work outside (the country), and they send money to their family so the women have already started (…to steer the household).” [Healthcare official]

Others in both VDCs stated there is no issue of empowerment at all.

“Women these days are educated well. So they have a good level of knowledge and information and are empowered enough to raise their issues and voice their concerns. So there is not an issue of empowerment.” [Healthcare provider]

Some do acknowledge that women don’t always speak up for an undefined reason.

“There is no issue of women empowerment at all; they are empowered enough and comfortable with voicing their concerns. But the fact they do not voice complaints doesn’t mean they are satisfied with everything we provide.” [Healthcare provider]

Mothers’ Groups also stated they’re empowered enough. However, they say the reason they don’t speak up about issues or concerns related to the services is the fact that they find the topic too personal.

“No, it would not matter if there was a FCHV or not if it’s a personal issue because we would keep it to ourselves and discuss it with the family. But if there are complications or health problems, then we will discuss it with everyone.” [Pregnant/recent mother]

DISCUSSION

Seven years after the start of the World Bank support Program for Accountability in Nepal (PRAN, 2010-2013), we reported on the social accountability mechanisms employed by the actors from the government as well as those existing at the community level in rural Baglung (Nepal). The main mechanisms that contribute to social accountability in maternal health through disseminating information, discussing issues and concerns, and negotiating solutions are positioned in formally installed structures of the health sector, mainly the Mothers’ Groups, FCHV and HFOMC.

Our informants indicated that the original motivation for the oldest community movement, the Mothers’ Groups, is vanishing now that it is incorporated in the formal health sector policy; for example, there are top-down cuts in incentives for the FCHVs to facilitate the Mothers’ Groups on maternal health issues. A decrease in meetings involving FCHVs is a sign that the accountability loop is under pressure. In 2010, Glenton et al23 investigated the extent to which decision-makers understand FCHV voluntary motivations and match them with appropriate incentives to influence the sustainability of the FCHV mechanism. Stakeholders viewed the FCHVs as primarily being motivated by social respect and religious and moral duty. They admitted to seeing the need for incentives. However, regular wages were said not only to be financially unfeasible, but also a potential threat to the FCHVs’ respect from the community and therefore their motivation.23 More than seven years later, this tension is still present. The FCHVs mentioned that when some people of the community suspect that the FCHVs get a regular wage, they do not treat the FCHVs with the respect they deserve.

There is a lack of information regarding maternal health in the district. There is no standard monitoring system for the number of Mothers’ Groups held in the district. Currently, the Baglung district has no information about how many mothers are actually receiving the maternal health information.

It is a reason for concern that the HFOMC does not feel heard at the district and national levels when voicing a problem or requesting a budget. When a budget is not allocated, the HFOMC faces difficulties fundraising for health services or requesting NGOs. However, even if budget cannot be granted, this information must be forwarded back to community levels to comply with the social accountability loop, so they are aware their requests do get handled and their voices are heard. However, there seems to be a barrier in the response to requests from the district level down to the HFOMC and FCHV, which puts the accountability loop under pressure, for example causing a decrease in requests, issues and concerns voiced.

Strengths and limitations

There are several strengths of this study. First of all, stakeholders at multiple levels were interviewed to ensure a system-wide view of the current situation could be created. The interviews were transcribed verbatim to prevent important information being excluded from analysis.

One limitation of this study is the language barrier and the necessity of a knowledgeable interpreter. The interpreter accompanying the interviews worked for the District Public Health Office. This may have affected the information given by the communities, as the interviewees might like to keep certain issues confidential. However, the status of the translator ensured that interviews could be organised in a timely fashion. It is also possible that some information may have gotten lost in translation, resulting in missed opportunities to probe deeper. A DPHO official who facilitated the data collection checked the draft paper for misinterpretations. The amount and quality of information gathered were shown to be sufficient to understand the actors’ perceptions in the accountability loops of the maternal health programs.

Participants might have understood concepts such as empowerment in a different manner. The inconsistency in opinions regarding women’s empowerment by actors might be due to different conceptualisations of empowerment, for example speaking up in the presence of more powerful actors, or autonomy to steer one’s own life in the absence of one’s husband, or the leadership to manage one’s own pregnancy as the healthcare providers would like to see it.

Another limitation is that the study is limited to the two VDCs in Baglung district, and few but important key respondents. The amount and quality of information gathered was very rich which enabled us to understand the actors’ roles and perceptions in the accountability loops of the maternal health programs in the study sites. In addition, this information could be triangulated with a parallel study under supervision of the second author in the Doti and Kailali districts, in these districts two weak links in the accountability chain too have been found between the same actors.

Recommendations

To further improve the maternal health situation in Baglung, Nepal, through social accountability, several actions are relevant. First of all, the feedback loop from the central and district levels back to the community is not functioning well. It is of great importance to repair the feedback loop as the current way of functioning might demotivate people on the community level when no clear response is received regarding the community’s demands and needs; a lot can be won here. Second, expand the family involvement when disseminating information. This currently occurs on a very small scale in the rural VDC studied (Amarbhumi), while in the accessible VDC studied (Hatiya), this is still something they aspire to achieve.

Adequate incentives for Mothers’ Groups and FCHVs are required as currently fewer meetings involving FCHVs are being organised in the district. FCHVs from both rural and accessible VDCs state this will motivate them to deliver adequate work. A lot can be won by small investments.

With regard to further research, we suggest an intervention study to train the participating district officials and central governmental officials in communicating systematic updates of their response to the lower levels that voiced the concerns, and thus closing the gap of silence after presenting their needs. It is important to investigate the underlying reasons explaining why women do not voice service-related concerns while stating they are sufficiently empowered.

CONCLUSION

There are many ways for women to acquire information and voice their concerns (dialogue & negotiation). The main mechanisms experienced by the women are the FCHVs, HFOMC and Mothers’ Groups, notably the formally structured part of the health sector. There seem to be some issues within the social accountability loop, which hinders its functioning to its full capacity. These parts of the accountability loop in maternal health all influence each other. If one part does not function, the other parts will also suffer. The first issue occurs at the community level. Mothers do not voice any issues or concerns related to the services or their right to care to the FCHVs, health facility or HFOMC. The second issue is a lack of dialogue between HFOMC and other health actors. The HFOMC mainly discusses issues with the health post and tries to resolve any concerns with its own resources. The third issue is a lack of response regarding a concern or budget request from the district or central government. This causes the HFOMC to believe its concerns or requests are not being handled, which will eventually cause them not to feel heard and to submit fewer concerns to the district and central government levels. As a result, the fourth issue is that the HFOMC has no information to transmit to the FCHVs and the Mothers’ Groups, which in turn will prevent them raising issues or voicing concerns as there is no response regarding how or if it is handled. These four main issues in the social accountability loop need to be addressed in order to optimise social accountability in maternal health.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript is a part of the second author’s Erasmus Mundus Joint Doctorate (EMJD) program under International Doctorate in Transdisciplinary Global Health Solutions. The authors would like to acknowledge the European Commission for providing the scholarship for the doctoral program. The authors are also grateful to the research assistant Shreesti Uchai, all staff from District Public Health Office, Baglung, Nepal, and all others who supported the collection of the data. We would also like to thank the participants for their time and sharing their experiences and perspectives.

Ethical approval

The technical approval for the study was granted by the VU University Medical Center (VUmc)c Science Committee of EMGO+ Institute in the Netherlands (WC2014-035 HZ). The ethical approval for data collection in Nepal was obtained from the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) (Reg. no. 22/2016). Participants were asked to confirm their consent and were assured of their privacy and confidentiality prior to the interviews or focus group discussions.

Competing interests

The authors completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available upon request from the corresponding author), and declare no conflicts of interest.

Correspondence to:

Saskia Oostdam

Athena Institute for Research on Innovation and Communication in Health and Life Sciences

VU University

De Boelelaan 1085

1081 HV Amsterdam

The Netherlands

[email protected]