In the People’s Republic of China (hereafter mainly referred to as China), health is one of the most publicly discussed issues.1 China is facing the problem of a huge increase in health care costs, due to population ageing and technological progress. Who is to pay for all this?

In the last decade, the Chinese Communist Party has heavily subsidised health care. From 1978 to 2016, total governmental spending in the health care sector doubled from 3% to over 6%. It is unclear, however, whether the state can carry an annual financial burden of Chinese Yuan (CNY) 4,634.5 billion in the long run.2 And even if proper financing of the health care system could be guaranteed, this may not necessarily correlate with the actual quality of medical treatment.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, China has been experimenting with DRG systems.3 As a result of the implementation of DRG systems, finding the financially most viable categorisation has taken precedence over ensuring the quality of the actual medical treatment or procedure. As a consequence, pilot schemes mostly relate to the quality assurance of medical treatment methods such as pay-for-performance models (P4P). These newer developments in hospital quality management shall be outlined on the basis of literature research.

Over the last few years, there have been numerous publications regarding health care provision in China4,5; for the most part, however, hospital quality management is merely cursorily mentioned in these scientific papers. A notable exception is the World Bank’s publication entitled “Deepening Health Reform in China”,6 which offers a recommended course of action. Contrary to this, the main objective of this article is the systematic presentation of hospital quality management in China and currently related challenges.

HEALTH CARE FRAMEWORK

The transformation from a communist planned economy into a socialist market economy has an effect on the health care system, which has changed from purely employer-driven health insurance to a true state-run health care system.

Towards the turn of the millennium, this process had led to undesirable developments with only about 5% of the rural population having access to health care.7 The central government began to support the reconstruction of the health care system with state funds. The “National Health Service System Planning Outline (2015-2020)”8 and the “13th Five-Year Plan to Deepen the Reform of the Medical and Health System”9 have proposed changes that will allow the entire population to have access to health care by 2020. To date, around 95% of the population has been provided with rudimentary health insurance. For the rural population and townspeople who have no status as employees – such as students – half of this insurance is subsidised by the state. For employees, compulsory health insurance applies, to which both employer and employee contribute.8

The number of treatments has increased by 2% year over year, including those in private medical facilities, which show an annual increase of 13%.10 The trend of an ever-increasing number of medical treatments will continue with the rapidly ageing population and the rise in chronic illnesses which can be attributed to changes in lifestyle and environmental conditions.

What plans does the Chinese government have for the future of its health care system? On 25 October 2016, the Party and the State Council published its “Healthy China 2030” Plan.11 It is a plan of action that outlines the projected improvement of health care up to the year 2030. According to this plan, life expectancy for 2015 was calculated to be 76.34 years; it is expected to rise to 79 years by the year 2030. The infant mortality rate had fallen to 8.1% by 2015 and it is to be reduced to 0.5% by 2030.11

In addition to these changes in health care, an organisational state reform was declared at the National People’s Congress in March 2018. Consequently, the responsibility for health care was transferred from the National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC) to the National Commission for Health, which is operated under the auspices of the State Council as a Ministry. At the local level (for instance at provincial level), the relevant authorities will be formed accordingly in the near future. Until that time, they will be referred to as the Health and Family Planning Commission (HFPC).

Organisation of Chinese hospitals

In the People’s Republic of China, 90% of medical treatment is carried out in hospitals, so that there are currently almost no independent doctors, i.e. the hospital is visited even for minor illnesses.12 There are about 25000 hospitals in China, whose financing and equipment vary greatly. The Chinese west is basically much poorer than the eastern coastal areas, which has a noticeable impact on the financing of hospitals and the quality of treatment.13

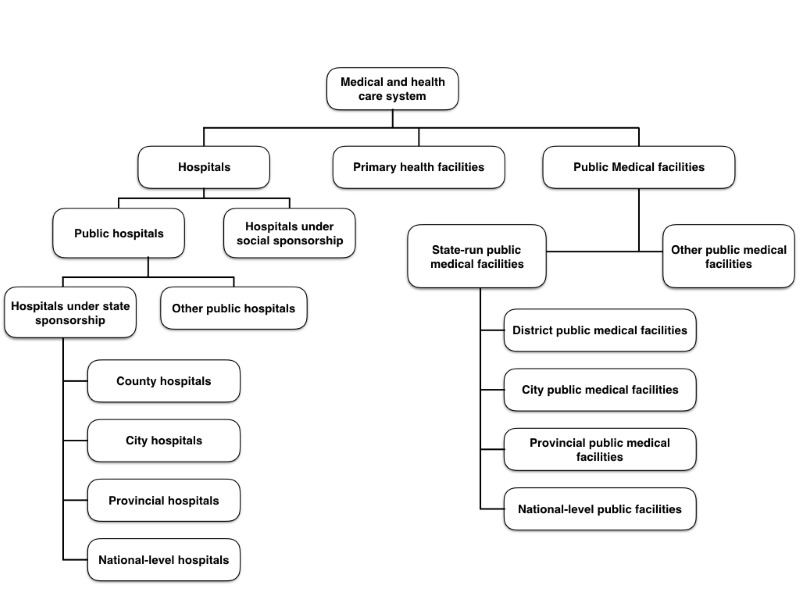

The Chinese hospital system is organised as shown in Figure 1.

Health care providers in China receive payments from the following sources: sale of medicines; private payments from patients; health insurance payments, which will gradually be converted to prospective reimbursement; and direct public funding related to public health goods as well as subsidies.6

Chinese hospitals are divided into three medical care levels. There is care level one, care level two and care level three. The difference between the individual levels lies in the bed capacity and the level of medical facilities in the hospital. Care level one hospitals are located in towns and municipalities, feature a basic set of medical facilities and have up to 100 beds. They offer a basic level of medical services. Care level two hospitals are located on a supra-regional level. These hospitals are adequately equipped to perform demanding medical procedures and surgery, and have 100 to 500 beds. Lastly, care level three hospitals are located in large cities. Their equipment is state-of-the-art – often from well-known international suppliers – and they offer space for more than 500 patients (see Table 1).14 The following indicators for hospitals and staff are provided for in the National Health Service System Planning Outline (2015-2020) (Table 2).8

Payment of hospital doctors

The salary of Chinese doctors who work full-time consists of a basic salary, bonuses and other benefits. The basic salary consists of a position salary, an age supplement, a performance supplement and state subsidy.12 The NHFPC, the Ministry of Finance and the Labour Office set the latter. A national salary survey,6 conducted by the NHFPC in municipal hospitals of care level two and three, shows that the basic salary accounts for only 13-14% of the total salary of medical staff in public hospitals. Benefits and supplements account for 14%. The remaining part of performance-related wages and salaries, as well as bonuses linked to hospital services, amounts to as much as 74%.6

Two bonus models are currently used in China: the surplus distribution model and the performance model. The surplus distribution model is primarily used, which creates an incentive to increase turnover rather than to improve quality. The performance model, too, rewards the number of cases treated and not the quality of the procedure or treatment provided. Both models function as a two-stage system. In the first stage, the bonuses are divided between the medical departments within a hospital, and then among the staff within these departments.12

The problem is that hospitals can autonomously determine additional payouts, for which there are no national standards or regulations.16 This means that the chief physician of the respective department (or the entire hospital) can pay out additional benefits at his discretion. In most hospitals, it is common practice to pay the same amount to all to avoid resentment among the staff. This approach offers no incentive for physicians to tailor their services to quality criteria.16 In addition, many doctors work overtime. About 40% of the medical staff work more than the legal 40 hours a week. 20% of employees work more than 50 hours a week.16 Such working hours are hardly of any benefit to the quality of medical treatment.

The salary system must be reformed because it is conducive to corruption. Anyone who spends a lot of money on a treatment has high expectations regarding the results of the treatment. Failure to provide these results will often lead to violent disputes between patients and medical staff.17 This has reached such an unprecedented level that the “Healthy China 2030” Plan has included improvements to the pay system for medical staff, and explicitly defines violence against doctors as a problem to be resolved. One solution is believed to be a salary system that is in accordance with international standards.11 Disputes over the outcome of medical treatment could possibly be alleviated through improved hospital quality management.18

Legal framework

Legislation in China is passed through the legislative and executive branches, but the laws and ordinances are to be understood as a declaration of intent by the Communist Party and are usually not legally binding. Due to a lack of control instruments, only 10 to 20% of laws are actually implemented by the executive authority.19

Guidelines for improving medical quality

On 26 September 2016, the Medical Quality Management Measures were adopted.20 Until then, there had been no regulations on medical quality21; the relevant provisions were interspersed throughout the “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Practicing Doctors”,22 the “Regulation on the Administration of Medical Institutions”23 – which regulates the management and further development of medical institutions – and other regulations. In 2011, the NHFPC also issued various guidelines on how to improve medical quality, on how to deal with medical errors and negative reporting, and on pilot projects.24,25 These include projects aimed at reducing the prescription or use of antibiotics and at improving patient consultation through extended patient-doctor contact.17 In addition, in 2015 the State Council initiated a reform of quality assurance and quality improvement for both municipal public hospitals26 and district/county hospitals.27 Although it calls on the respective governments to improve quality assurance, it does not specify how this should be achieved.

Draft legislation

The adoption of a law on health care has long been pending. A first draft was submitted to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress for first reading on 29 December 2017.28 The declared objective of the law is to clearly establish the responsibilities at the various levels of government in order to warrant the health care of China’s citizens.28 The new draft fulfils this objective only to a limited extent. Whereas the old draft (which was never published, but which is to be considered trustworthy) stated that the NHFPCs were responsible for health care at national level, and the corresponding departments were responsible for health care at local level, and that a national institution for monitoring quality management should be set up,29 the new draft no longer contains any statement about this. Now it reads that the relevant departments of the State Council are to establish the basic standards for medical health care facilities. Public medical institutions fall within the remit of the relevant levels of government, and the latter also have to supervise the public hospitals. If this form of surveillance does not work, talks should be held between the higher-ranking government agency and the authority which encountered the problems. Local governments must set up a quality assessment system for medical and health facilities for monitoring purposes.28

HOSPITAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT

Until March 2018, defining the procedures and standards was the sole responsibility of the NHFPC. It now officially lies with the National Commission for Health/Health and Family Planning Commission (HFPC), which however has not shown any signs of activity until the time of preparing this article. From district level upwards, the corresponding government departments are responsible for hospital quality management.20 This is to be executed by the “Committees for the Evaluation of Medical Institutions”, which are to be established by the local people’s governments at district level in their respective territory. They are to offer suggestions for improvement to the relevant institutions.23

External quality reviews

According to the Medical Quality Management Measures [2016], the administrative departments are required to establish “quality control organisations” at all levels. An interview system must be set up at local level to report serious quality deficiencies. The person responsible must provide appropriate clarification and, if necessary, penalties will have to be imposed. These penalties however are not further specified for individuals.20

The relevant HFPC departments at all levels must include the review results, in the form of Key Performance Indicators (KPI), on the evaluation of medical facilities and their primary management staff. In this way, an evaluation system has been introduced that should enable performance assessment of individual actors.20 The following indicators are used to evaluate medical staff: responsible conduct, workload, quality of service provision, qualifications, cost control and patient satisfaction.8

Up to CNY 30,000 will be fined by the departments of the HFPC if the medical facility does not establish a department for medical quality management, has not created regulations for quality management (or has not or insufficiently implemented these), if a quality deficiency or safety incident is covered up, or if information for medical quality management is not appropriately supplied.20 There is no direct exchange of information between the individual medical institutions and the control authorities at state level, which is why external quality control is only of limited effectiveness.30

Internal quality reviews

Internal quality management has developed in three stages: Initially, quality assurance units were set up, which were specifically linked to their respective departments. Thereafter, general quality inspection units were established in the actual hospitals. Finally, independent quality control departments were established, responsible for quality management planning, prognoses, guidance, monitoring, inspection, evaluation, and the issuing of rewards and penalties. Due to regional differences, largely varying hospital types and levels, and great discrepancies in the knowledge levels of quality management, all three institutions currently coexist in China.31

The main person responsible for quality control in any given hospital in China is its respective managing director.32 Care level one hospitals are required to establish their own quality assurance departments. A so-called Medical Quality Management Committee is to be set up in all hospitals from the second care level up, which will be responsible for implementing quality assurance procedures and systems.20 The Medical Quality Management Committee analyses the hospital quality reports in cooperation with the assembly of doctors. The results are reported to the organisation for quality management at provincial level, and a comparative data analysis is carried out there.33

As criteria for evaluation, the NHFPC has issued “Guiding Opinions on Strengthening the Performance Evaluation of Public Health Institutions”,34 the current official version of which dates from 2015. They contain a publicly available hospital performance evaluation index and guidelines for creating performance evaluation documents for the specialist departments in hospitals.35

The hospitals set up a steering committee for the performance evaluation of the specialist departments (hereinafter referred to as “Steering Committee”) and a department for performance evaluation implementation (hereinafter referred to as the “Implementing Body”). The Implementing Body shall draw up an evaluation plan for the departments. The head of department appoints an internal evaluation team, formulates the internal evaluation plan, reports to the Implementing Body and rates the performance of the department’s employees.35

The evaluations in the specialist departments are carried out annually and an evaluation report is submitted to the Implementing Body. The latter carries out audits and assessments, publishes the results within the hospital, obtains feedback from employees and prepares an evaluation report. The Implementing Body prepares an assessment report and forwards it to the Steering Committee. The latter in turn approves the evaluation results and publishes them throughout the entire hospital. The results of the performance evaluation serve as a basis for allocating hospital resources, as well as for the support and funding of staff training. Departments with good ratings receive rewards for their performance and those with poor results will be awarded fewer resources.35

Common quality indicators include average length of hospital stay, hospital admission and discharge data, the total number of medical cases, hospital bed occupancy rates, use of antibiotics, complaints and reports concerning adverse medical events, etc.33 Evaluation criteria include the implementation of the quality assurance reforms, the annual work plans, the increase in participating departments, the effectiveness of the implementation of hospital reforms and the creation of positive incentives, such as the increase in the budget bonus, the advancement of managerial staff and the support and funding of staff training and further education.35

Regional differences

Hospital quality management varies widely in tertiary, private hospitals and public hospitals at district level, with the main problems being inadequate organisation of internal quality management, understaffing of medical professionals and insufficient training for the staff that they do have.31 A survey of 28 hospitals has shown that most hospitals have an independent quality control department that reports directly to the managing director. In other hospitals, the managing directors themselves are responsible for the hospital quality management. In the third variant, the medical department has established a fixed division of labour to carry out medical quality management measures. If the ratio of beds to persons responsible for quality management is considered, it is clear that, percentage-wise, hospitals with more beds employ more persons in the area of quality management.31 This would suggest that quality assurance in large hospitals is better than in small rural hospitals (Table 3).

Problem areas of medical quality reviews

Since the quality of treatment is monitored very inadequately, hardly any reliable information is available on this subject. Some hospitals limit their quality assessments to actual cases of illness.31 Random sampling has shown that the quality of management practices in public hospitals is below the average of OECD countries. Furthermore, public hospitals neither have the authority nor the autonomy to reward high-quality health service providers and eliminate bad ones.17

Another problem with a view to scientific investigation is the poorly managed archiving of quality control data. Filing of documents and relevant data is often not carried out adequately, and often the data itself is also incomplete, making it partly useless for further analysis. In many cases, patient records and archives are handwritten only, which makes effective assessment of these virtually impossible. Digitisation of the entire process of registration and archiving is therefore a top priority.36 The promotion of transparency of hospital information through regular disclosure of the financial situation, performance statistics, quality of safety, price levels and development, inpatient hospital expenses, etc. has been repeatedly requested in various official communications,26,27 but rarely implemented in reality.

The 2016 Medical Quality Management Measures have been widely criticised for omitting guidelines for the organisation of hospital quality management, even though they do provide for specifications on the education of medical staff. Another problem is that in many cases the departments for hospital quality management are on the same hierarchical level as the medical departments themselves. Responsibilities are either shared among different chairpersons, or reside in the hands of one single person, which makes for a rather unclear distribution of competences and a lack of organisational transparency. The departments for quality management should be in a position to report directly to the hospital’s executive management or, at the least, be placed at a higher hierarchical level than the individual specialist departments.31

China’s hospital management is characterised by incentives that reward the quantity of care rather than the quality. Such abnormal encouragement to promote profit and increase treatment rates, rather than rewarding quality, has a strong influence on management practices and the provision of services in all medical facilities.20 Although the initiated reforms have improved the quality of treatment, many public hospitals continue to prioritise profit.37 Apart from investing in more advanced medical equipment, which proves to be very profitable, there is no incentive for hospitals to invest in enhancing the less visible aspects of quality, such as the course of treatment. China lacks a well-structured organisation that also pays attention to the quality of medical treatment. What is more, most hospital managers have not enjoyed sufficiently adequate management training.17

Pay-for-Performance in connection with the payment of hospital physicians

One concept for improving the quality of medical treatment is a pay-for-performance system for doctors in public hospitals. This model presents a possible approach to the improvement of medical quality in the People’s Republic of China.12 First introduced in 2009, while being the subject of several pilot projects since then,38 its aim is to dissolve the conflict of interest that arises from a purely profit-oriented approach to health care. The objective to base service performance solely on the purpose of raising the hospital profit as well as the personal income of medical staff will have to be eliminated. Most hospitals are known to use methods based on Balanced Score Cards (BSC) and additional Key Performance Indicators (KPI) for evaluation purposes. Indicators for evaluation include number of patients, the quality of written hospital records, the number of consultations, patient satisfaction levels and recovery rates. The results of these experiments show strong differences.35

It has been shown in various pilot projects that the indicators that are used for these evaluations are difficult to classify, especially with regard to the qualitative aspects of medical care and treatment. For example, a cardiologist will treat two to three patients per day, while a general practitioner might have sixty patients on average. Furthermore, financial bonuses in terms of salary payments cannot be perceived as being completely independent of a hospital’s total profit, as they are additional payments that are subject to the general cost-related accounting schemes and overall financial performance of the hospital. It has been established as common practice that there are almost no differences in salary for doctors. As a consequence, doctors who work considerably more – both in terms of quality and quantity – are not financially compensated for their additional performance.

Finally, the local governments intervene in the performance evaluation of physicians by way of coercive measures. For example, in 2010, the city of Chengdu linked bonus payments of between 5% and 30% to patient satisfaction rates. The problem with patient satisfaction rates as a criterion is that it is based solely on subjective perception, has no direct relation to the quality of the medical procedure, and therefore is not an objective qualitative indicator.39

Among Chinese scientists, P4P is seen as a possible method for determining the payment of physicians that will enable an improvement in medical treatment quality. However, the performance workload as such should not be used as an indicator; the focus should rather be on the result of the treatment.35

CONCLUSION

In addition to the fundamental reforms in the Chinese health care system, which relate to medical care provision to the population, attempts are being made to improve hospital quality management. To this purpose, various pilot projects have been initiated. They are, however, not yet being implemented nationwide. P4P projects in connection with physician salary payments are a viable approach to improving treatment quality. Further research opportunities present themselves in this field, both in terms of literature research and empirical research. The projects mentioned in this paper represent only a part of the currently conducted experiments. With research focused exclusively on the use of P4P models in salary payments for medical professionals, the diversity of projects could be presented, and a “best practice” model could be developed. As of yet, some important areas in the field of hospital quality have not been covered, such as the development and validation of national standards for quality measures. The assessment and evaluation of quality standards in the individual facilities is only carried out rudimentarily. Many hospitals do not archive the data that would enable quality control. With this in mind, the organisation of archiving and the quality of the applicable data should be examined in more detail, as this is what most assessments of treatment quality are based on. Furthermore, there is a lack of coordination between the various interest groups. As in many other areas, there is a lack of clear delimitation of competences and of coordination between the individual institutions. Many of these difficulties also apply to other areas in China. However, hospital quality management is a particularly sensitive area, as many doctors in China are not well trained, overworked and underpaid. This inevitably leads to errors in medical treatment, which in turn undermines the trust of patients – and thus of the Chinese citizens – in their country’s health system. Before effecting further reforms in hospital quality management, investment should be made in reforming the training and pay structure of doctors.

Correspondence to:

Prof. Dr. Barbara Darimont

University of Applied Sciences Ludwigshafen

East Asia Institute, Rheinpromenade 12

67061 Ludwigshafen, Germany

[email protected]

Phone: +49 621 5203430

Fax: +49 621 5203477