Tobacco use, particularly cigarette smoking including environmental tobacco smoke is still a substantial contributor to the global disease burden.1 Smoking prevalence is decreasing worldwide, particularly in developed countries, although rate of decline has slowed down in recent years.2 The sustained presence of heavy smokers who are more addicted and less able to quit3 has led to emergence of “hardening hypotheses”.4 Light smokers are more likely to quit than the heavy smokers, thus leading over time to a decrease in light smokers and a relative increase in heavy smokers. Over time these heavy smokers become much harder to reach, and it becomes more difficult for them to quit,5 leading to a “hardened” population of smokers who are more resistant to quit. However, it has also been argued that the process of ‘hardening’ may not occur due to dynamic nature of cohorts of smokers arising from changes in subpopulations of quitters, smokers who die and new smokers.6

The ‘hardening hypothesis’ has been tested using data on smoking behaviours in United States,7–9 Australia10 England,11,12 Norway13 and Italy.14 The ‘hardening hypothesis’ has also been evaluated in several studies using varying definitions for ‘hardcore smoker’ (HCS). In general, HCS was defined based on the constructs of duration and intensity of smoking, time to smoke the first cigarette of the day, number of quit attempts made, intention to quit, and knowledge about harms of smoking.6,15 Additionally, empirical evidence for the "hardening hypothesis " has been evaluated using repeated cross-sectional survey data16,17 and national population monitoring data.16 Based on Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS), HCS was defined using different constructs and prevalence, and factors associated HCS were reported.18,19 A study from Poland assessed factors associated with HCS including the constructs listed above to define HCS18 while another study from Bangladesh, India and Thailand tested the association of HCS with socio-demographic factors only.19

Studying the population prevalence of HCS and the proportion of current daily smokers who are HCS helps design tobacco control policies and set up support services for smoking cessation targeted at the ‘hardened’ smokers.20 In this paper, we use a five-item construct for HCS based on definitions used in previous studies. We report sex-specific, country-wise proportions of HCS among the current daily smokers, population prevalence of HCS and estimated total number of HCS in 27 GATS countries.

METHODS

We used publicly available data of the Global Adult Tobacco Surveys (GATS) (http://nccd.cdc.gov/gtssdata/Ancillary/DataReports.aspx?CAID=2), a series of nationally representative, cross-sectional household surveys done as a part of worldwide Global Tobacco Surveillance System (GTSS) to monitor tobacco use among various population groups. The GATS uses a standardised questionnaire to assess tobacco use behaviours among civilian, non-institutionalised individuals aged 15 years and above.21 In each GATS country, the residents of all regions were eligible to be sampled by a stratified multi-stage probability sampling technique. Within a selected geographic location, households were selected at random and within a selected household, all eligible persons were interviewed using a handheld device used for rostering and data collection, and one household member was selected at random for the interview. The implementing agencies in each country adapted the core questionnaire to suit the local tobacco use context. In all countries interviews were done privately by either a male or female interviewers, except for India, Bangladesh, Indonesia and Qatar interviewers were of same gender as the respondent. Further details about survey instrument, methodology etc. are published elsewhere.21 The sample sizes, response rates by sex are given in Table 1.

Main outcome variable

Based on previous studies respondents were defined as HCS, if they satisfied the following five criteria8: 1) is a current daily smoker; 2) smokes 10 or more cigarettes per day; 3) smokes their first cigarette within 30 minutes after waking up; 4) has not made any quit attempts during 12 months prior to the date surveyed; and 5) has no intention to quit smoking at all or during the next 12 months.

Statistical analyses

All the analyses were done on Stata/IC version 10 (Stata Corp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics were calculated for current daily smoking and five constructs of HCS including average of number of cigarettes smoked per day. The proportion of current daily smokers who were HCS was calculated for men, women and both sexes. To adjust for complex sampling design used in GATS, we used country sample weights to estimate prevalence rates and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). We used total and sex-wise population aged 15 years above from United Nations census data to estimate the number (in millions) male and female HCS in each GATS country. As a sensitivity analysis, we also estimated age-adjusted rates of current daily smoking and HCS, adjusted to the world population standard.22

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the year of survey followed by sex-specific sample size, median age of respondents and smoking status for each country. A total of 344,329 adults (164259 men and 180070 women) were surveyed, median age of the respondents varied between 31-55 years for men and 30-61 years for women. The weighted prevalence of current daily smoking among men was highest in Indonesia (57%) and Russia (55%), and lowest in Panama (4%) and Nigeria (6%). Among women current daily smoking prevalence was considerably lower: <1% in Nigeria, Egypt, Cameroon, Kenya and Malaysia and less than 5% in 12 countries; over 15% in Russia, Uruguay Poland and Greece (Table 1).

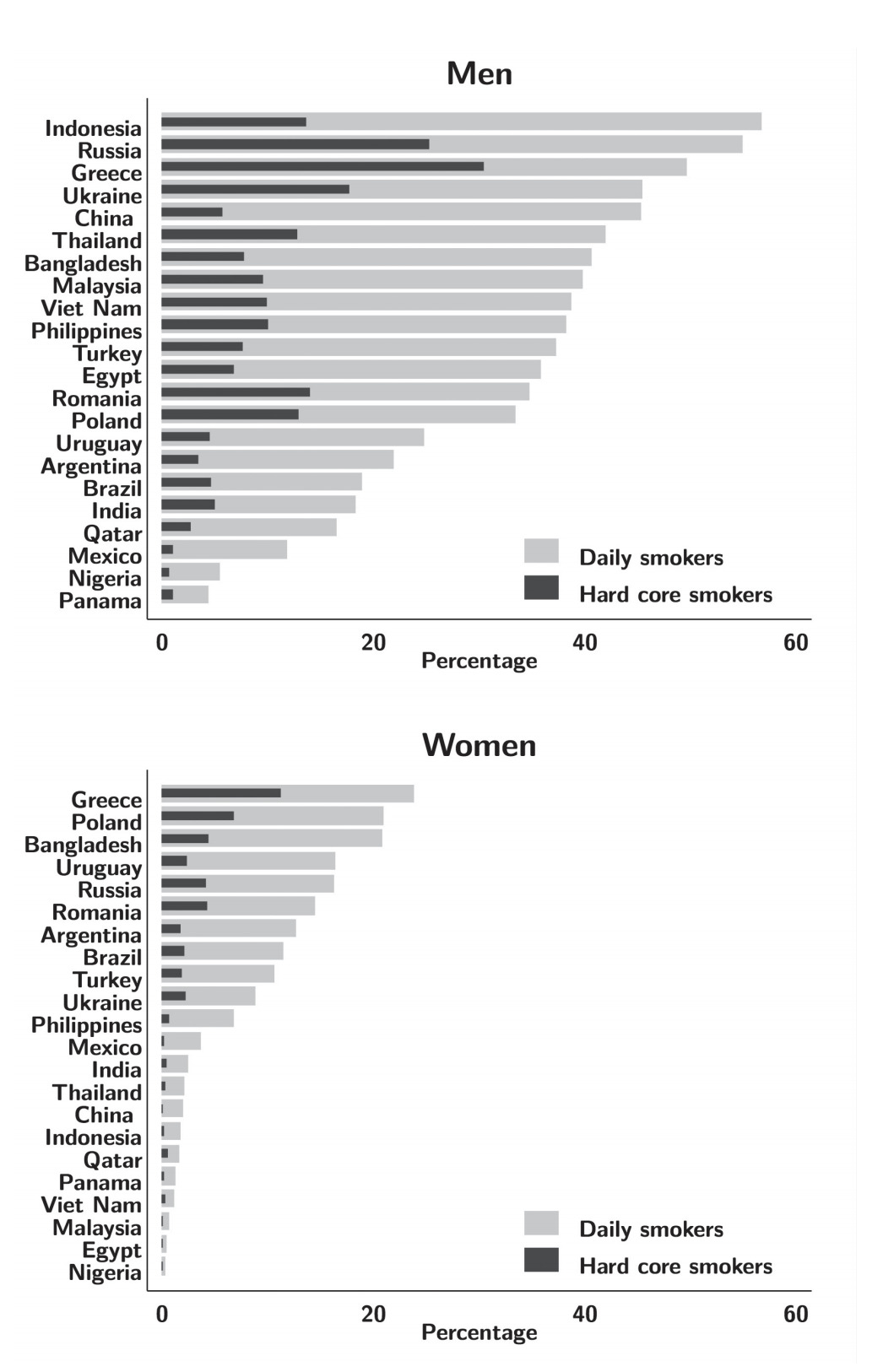

In all countries, the weighted population prevalence HCS was considerably higher among men than women, and in nine countries HCS prevalence was higher than 10% (Table 2). Among men, Greece (30.9%) had the highest prevalence, followed by Russia (23.8%) while in Argentina, Qatar, Panama, Cameroon, Kenya, Uganda, Mexico and Nigeria HCS prevalence was much lower (2.71-0.81%). However, in 25 countries the weighted population prevalence of HCS among women was less than 5.0% and in 17 of these 25 countries HCS prevalence was <1.0%; Poland (6.8%), and Greece (11.4%) had higher prevalence for women. (Figure 1 shows weighted prevalence of current daily smoking and HCS in each country).

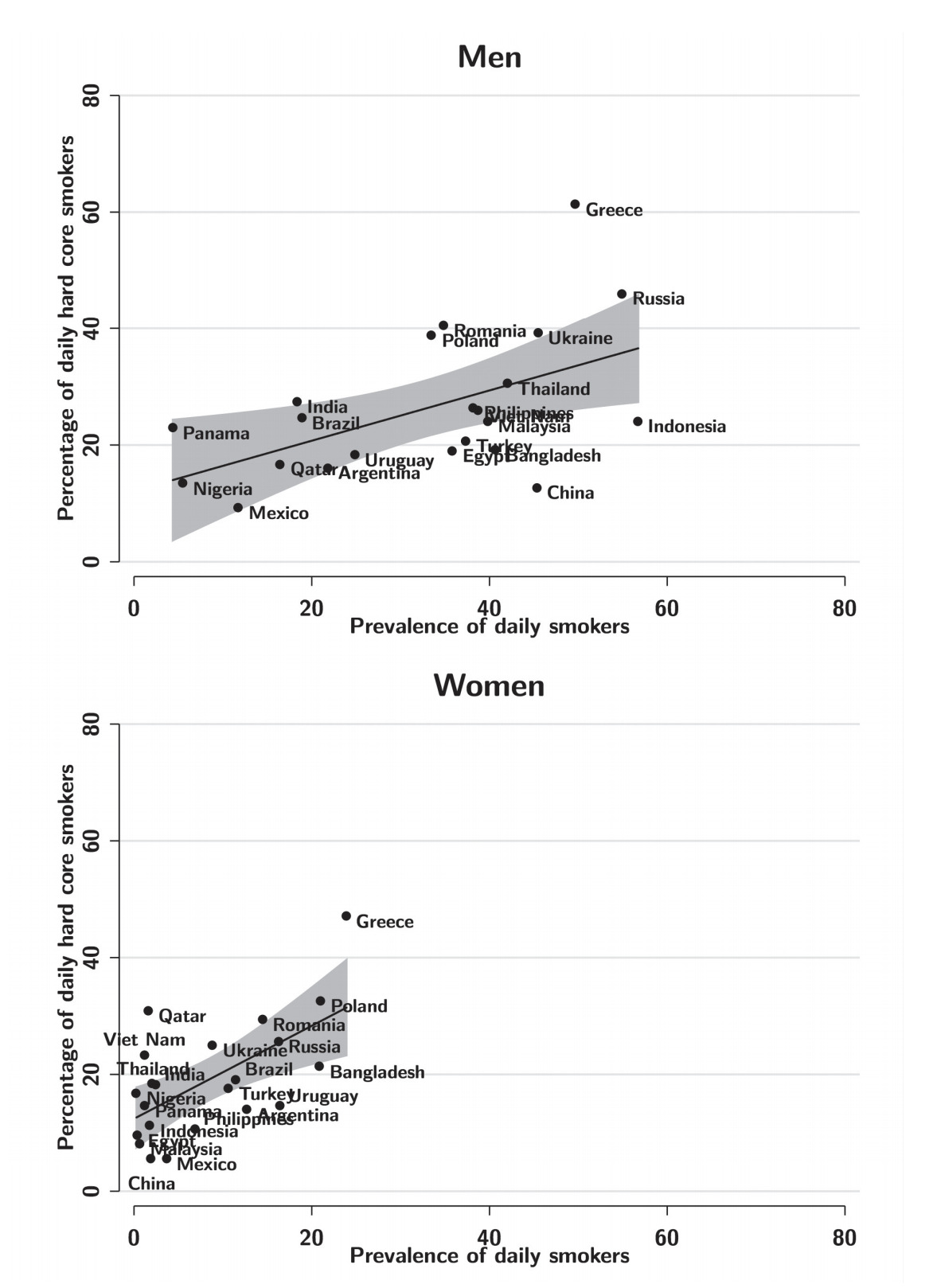

Overall (both sexes), proportion of daily smokers who were defined as HCS was higher in Greece, Cameroon, Russia, Ukraine, Romania and Poland (36.2-56.2%), in other countries the proportion was between 30% and 10%, except Mexico (8.3%). The proportion of male HCS was over 55% in Greece, and in Russia, Ukraine, Poland and Romania it was nearly 40%, whereas in most other countries it ranged between 30-15%. In all countries except Qatar, Bangladesh and Nigeria, the proportion of HCS was higher among males where prevalence of current daily smoking was also low. In both sexes, proportion of daily smokers who were defined as HCS tended to be higher among countries with higher prevalence of daily smoking (Figure 2).

Overall in 27 GATS countries there were an estimated 111 million HCS (101.6 million men and 12.4 million women, Table 3). Among the GATS countries, four countries together accounted for nearly 70% of all HCS: China (30 million), India (21 million), Russia (16 million) and Indonesia (11 million). China and India had largest burden of HCS in terms of absolute number of HCS due to their large population sizes. India and China had relatively lower prevalence of current daily smoking than Greece and eastern European countries of GATS which had very high current daily smoking prevalence. Age-standardization led to similar estimated prevalence for both daily smoking and HCS, compared to crude estimates (see Table S1 in Online Supplementary Document(Online Supplementary Document)).

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of HCS and the proportion of daily smokers defined as ‘hardcore’ varied widely between 27 GATS countries and sexes. In general, we found that proportion of daily smokers defined as “hardcore” was higher among countries with a higher prevalence of current daily smoking. In terms of absolute numbers China, India, Russia and Indonesia have very large numbers of HCS, whereas Russia has highest proportion of daily smokers defined as “hardcore”. In all GATS countries, women ranked lower than men in prevalence of HCS and number of HCS. Both prevalence of HCS and the proportion of HCS among current daily smokers were higher in high-income and upper-middle-income GATS countries, Qatar being an exception to this.

A strength of our analysis was a robust survey design of GATS, which generates nationally representative samples of men and women. The standardised methodology and survey instrument of GATS enabled us to construct a definition of HCS for cross-country comparison.23 Nevertheless, estimates reported in this paper should be interpreted with caution against the possible limitations inherent in GATS design. Self-reported smoking behaviour is known to lead to under-estimates due to smoking-related stigma.24 Furthermore, social desirability bias related to quit attempts and intentions to quit may have resulted in underestimation of HCS.25 Both duration of smoking as well as smoking intensity (ie, daily number of cigarettes smoked) indicate nicotine addiction but duration of smoking could not be computed in many low-income and lower-middle-income GATS countries because of missing data on age of smoking initiation. The surveys we analysed were implemented at different time periods, smoking patterns change over time and are sensitive to country-specific tobacco control policies2; hence our results should be interpreted in the context of the local tobacco control environment in the GATS countries.

The prevalence of HCS among high-income countries has been well reported and ranged from 16% in the UK11 to 6% in Norway.13 Our estimates varied widely and ranged from 21% in Greece to 0.4% in Nigeria. However, our estimates of HCS are not comparable to those from high-income countries due to heterogeneity in the constructs these studies used to define a HCS.15 Given the relationship, we identified between daily rates of smoking and HCS, our estimates may also differ from high-income countries because the prevalence of daily smoking differs as well. Two prior GATS-based studies used different definitions for HCS and reported a population prevalence of HCS of 3.1% (India), 3.8% (Bangladesh) and 6.0% (Thailand)19 whereas 10.0% in Poland18 which were nearly same as our estimates.

The hardening hypothesis has implications for tobacco control, since when the prevalence of smoking decreases it would make sense to target HCS to achieve further reductions.5 Studies on HCS have primarily been based on cross-sectional data.12,14,18,19 Additional studies that have examined sequential cross-sectional surveys have provided some evidence against the ‘hardening theory’13,17,26; however, one study reported that hardening may be occurring in the UK.5 Nevertheless, we are only able to provide cross-sectional estimates of HCS for 27 GATS countries. Some GATS countries have a huge burden of estimated population who are HCS, mainly among men in China, India, Russia and Indonesia. These estimate numbers have implications for tobacco control since smoking cessation can help to avoid a substantial tobacco-attributable mortality, particularly in low-and-middle-income countries (LMIC) currently experiencing epidemic levels of smoking.27 Moreover, these numbers have implications for healthcare services in LMICs which typically neither provided smoking cessation services28 nor implemented tobacco-related training programs healthcare professionals29 as per the recommendations of FCTC Article 14 or the FCTC Article 14 guidelines. LMICs with higher burden of HCS and low quit rates are likely to require larger healthcare costs to implement smoking cessation services.

Tobacco control strategies should consider smoking intensity, duration of smoking, time to smoke first cigarette, as these factors are known to be associated with tobacco dependence.30 More intensive and universal measures should be undertaken to achieve higher quit rates among all daily smokers.5 Reaching out to the hardcore smokers who lack motivation (don’t want to quit) and have severe nicotine addiction (can’t quit)17 requires a more holistic approach. Motivational interviewing maybe one of the approaches to help smokers decide to quit,31 as it is well known that smokers who are in contemplation stages are more likely to remain tobacco-free.32 HCS constructs in most studies including ours do not include socio-economic deprivation and mental health which are associated with “hardening”.14 As smoking is also known to be common among those with socio-economic deprivation33 wider community level interventions, such as health promotion and socio-economic development may not only help cessation but could also potentially help to decrease smoking initiation.34

In addition to conflicting reports on the ‘hardening hypotheses’, there is also a lack of consensus on uniform definitions of hardening across the published literature. Hence, there is a need for further studies defining HCS based on all the four domains of constructs described by Edwards et al.17 Current conflicting literature, mainly from developed countries, has tested the ‘hardening hypothesis’ with sequential cross-sectional surveys10,11,13,16,17,26; cohort studies on daily smokers who cannot quit would confirm the hardening hypothesis and examine the changes in proportion of HCS over time.

CONCLUSIONS

HCS constitute a fifth to third of daily smokers in some GATS countries, which presents challenges to tobacco control efforts. As the proportion of HCS tends to increase with the prevalence of daily smoking, efforts should be made to counter smoking initiation. Further HCS also poses a challenge to health services in LMIC where smoking cessation services are sub optimal. Future studies should include all four domains of HCS to better understand about “hardening hypothesis” in LMIC.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Centre for Disease Control for making the datasets of Global Adult Tobacco Survey that enables us prepare this manuscript.

Ethics approval

All the Global Adult Tobacco Surveys were approved by ethical boards of surveys countries and CDC, Atlanta. The data used for this manuscript are available in the public domain are de-identified. Therefore, a separate ethical approval was not required for this manuscript preparation.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding.

Competing interests

The authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare no competing interests.

Correspondence to:

Chandrashekhar T Sreeramareddy

Department of Community Medicine

International Medical University

126, Jalan Jalil Perkasa 19

Bukit Jalil

57000 Kuala Lumpur

Malaysia

[email protected]