Under-5 child deaths are a global concern irrespective of the nation, caste, religion, and other socio-demographic differentials. Despite significant progress in reducing neonatal and child mortality rates by 54 and 61 percent respectively, between 1990 to 2020, World Health Organization (WHO) highlighted that under-5 deaths are still highly prevalent, especially in low-middle-income countries (LMICs).1 More than 5 million children die annually before their fifth birthday, whereas 2.4 million children die within a month of birth.2,3 Globally, the probability of neonatal deaths was higher, followed by the infant (11 per 1,000 live births) and child (9 per 1,000 live births) in 2020.3 Moreover, the estimates also suggested that about 29 children under-5 years of age died annually per 1000 live births (95% CI: 26.4-32.1) including 17.5 neonates (95% CI: 15.5-19.6) in Bangladesh.4 Despite the decline in death rates, the leading causes of deaths were shifting from different infectious causes5 to birth asphyxia or birth injury, prematurity, and low birth weight.6 The latest Bangladesh Health and Demographic Survey (2017/18) reported that the major causes are pneumonia, followed by asphyxia, prematurity, low birth weight, and infections-including sepsis.7 This changing pattern is necessary to evaluate the time and locations.

Urban Health Survey reported that 57 per 1,000 live births in urban slum areas died before reaching the age of 5, whereas the infant mortality was 49 per 1,000 live births and neonatal mortality was 31 per 1,000 live births (54% of the total under-5 mortality).8 Compared to the national estimates, the overall under-5 mortality in urban slum areas is 50% higher than the national average, and these areas experience a greater burden of child mortality risk.9 Moreover, deaths due to pneumonia, birth asphyxia, prematurity and low birth weight, congenital anomalies and birth injury were higher in urban areas compared to rural areas.7 Despite the effective services for family and child health welfare in Bangladesh, the high mortality rates in the slum areas raise questions about Universal Health Coverage (UHC). Furthermore, the primary healthcare systems in Bangladesh are more structured and interconnected in rural areas compared to urban areas, which specifically put the urban lower, migrated poor populations in more vulnerable situations. Studies have found that maternal and child healthcare services were comparatively less utilized by the urban slums,10,11 and this under-utilization might be associated with the increased child deaths in those particular areas. Previously, the death causes were assessed especially limited to neonatal death cases,12 and the causes of under-5 deaths were poorly evaluated in the urban slum areas. However, it is important to identify the causes of under-5 deaths to reduce the deaths to some extent by taking preventable measures from the socio-cultural perspectives.13

Recent surveys across the country have found that respiratory infection (18%) is a major cause of under-5 deaths, followed by birth asphyxia (16%), prematurity and low birth weight (13%), and other infectious diseases. Apart from these, drowning is also found to be a major accidental cause of child deaths.7,14 However, these estimates have varied across the country and settings.15,16 Risk factors of neonatal and child deaths were assessed in different settings in Bangladesh. It was found that the care-seeking tendency of parents, the mother’s education, birth practices and place of birth, sex of the deceased child, birth orders and birth weights, and breastfeeding practices were significant risk factors for under-5 child deaths.17–20 These risk factors were more prominent and influential in the lower resource settings where the delivery and healthcare facilities were in a questionable state.16

Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System (urban HDSS) can contribute to find out the current status of under-5 child mortality in the slum population as it conducts the verbal autopsy survey in the surveillance area. Verbal autopsy (VA) is a standardized method of identifying the cause of death developed for low- and middle-income countries where death registration is poorly maintained or non-existent.21,22 The VA questionnaire records the reported illness, symptoms, and information on pregnancy and intra-partum complications for neonates and children. It, therefore, facilitates understanding longitudinal trends in causes of death. To ensure effective healthcare services, children living in the slum must receive services that are suitable in terms of the current situation of child healthcare and mortality status. Therefore, this descriptive study was undertaken to show the overall distribution of death causes as well as also the proportion of distribution of deaths by socio-demographic characteristics of under-5 children in the selected urban slum areas in Bangladesh.

METHODS

Study area, design and population

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of the causes of under-5 deaths, collected from about 160,000 population who were registered and monitored through the Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System (urban HDSS). Since 2015, the urban HDSS (run by the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b)) collects data quarterly (3-month intervals on average) from the slum population. The urban HDSS area includes five slums in Dhaka’s north (Korail, Mirpur), south (Shaympur, Dhalpur), and Gazipur (Tongi, Ershadnagar slum) city corporations. Concerning the household distribution and under-5 children, Korail slum is the biggest (HH: 4,418, Under-5 children: 4,941), followed by Mirpur (HH: 2,869, Under-5 children: 3,191), Tongi (HH: 2,640, Under-5 children: 2,893), and Shaympur/Dhalpur (HH: 989, Under-5 children: 1,080). Details of these surveillance sites were provided elsewhere.23

Data collection

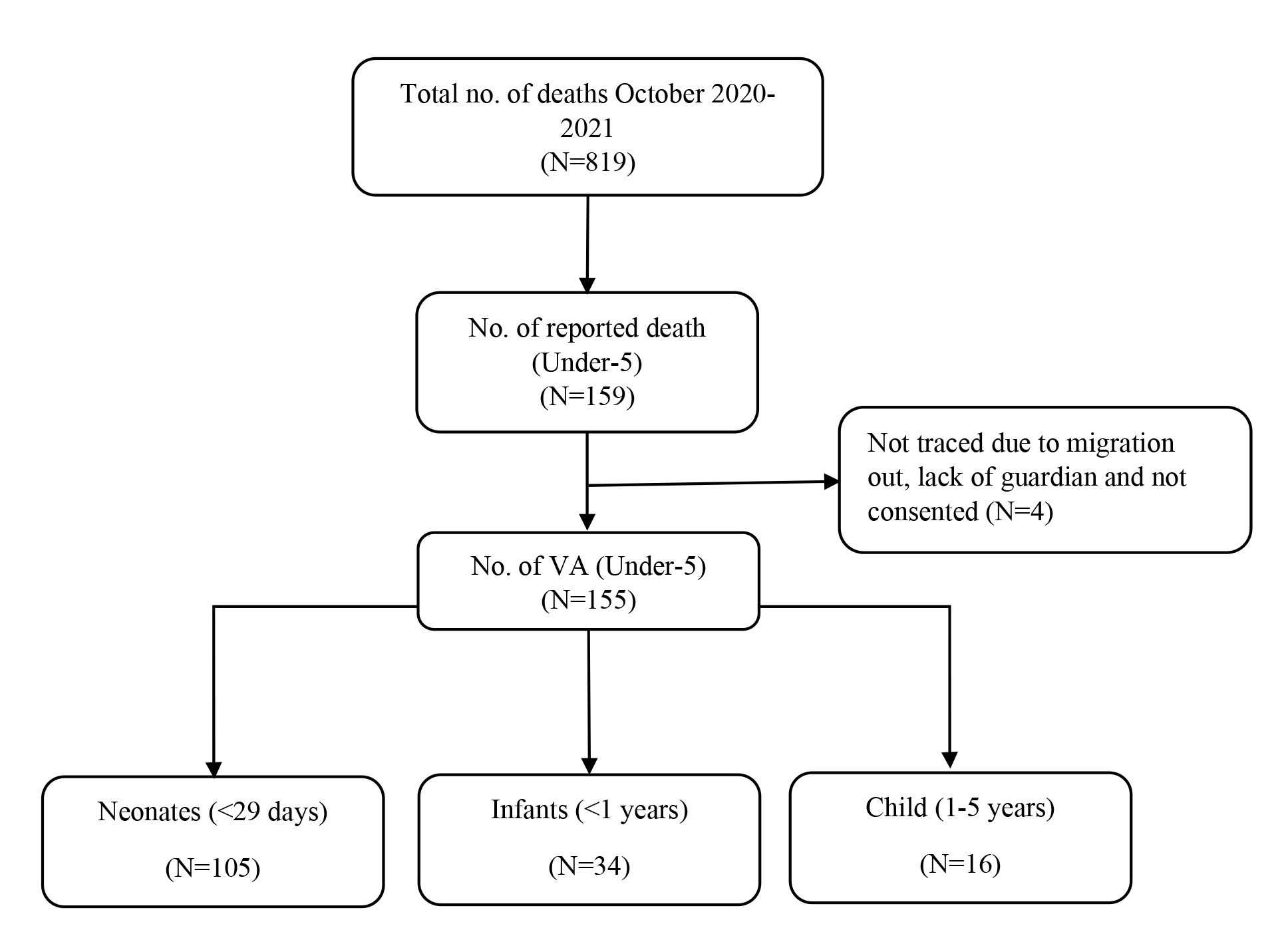

Death notifications

Field Workers (FWs), who were appointed and trained for the urban HDSS project, conducted regular visits to 40–45 households in the assigned urban HDSS area and collected major demographic information (birth, death, and migration—internal, in-migration, and out-migration) and maternal, neonatal and child health (MNCH) services, including child illness, infant, young, and child feeding (IYCF) practices, and child immunization. For deaths, FWs recorded the death events during their regular household visits, where they record the deceased ID, name, household (location of the household-de jure method), date of birth, date of death, and causes of death reported by the nearest personnel of the deceased using the tablet-based online platform. All the records were stored directly on the icddr,b online server. The information about the date of birth and death of the deceased children identified deaths for under-5s. From October 2020 to December 2021, a total of 159 deaths at the age of less than 5 years occurred. Among them, only 155 deaths were recorded in the form of VA. The rest 4 cases of these under-5 child deaths were not recorded in VA due to migration out of the family (Figure 01).

VA Data collection

Since October 2020, the urban HDSS has been collecting verbal autopsy information following the WHO standard verbal autopsy (VA) questionnaire for neonates (0-28 days), children (29 days to 14 years), and adults (15 years and above). The three types of VA questionnaires, neonatal (0-28 days), child (29 days to <15 years) and adult (aged 15 years and above) were used for collecting the causes of death information. The VA questionnaires were written in Bengali on tablets for the verbal ease of the FWs at the time of the survey, and responses were recorded in Bengali, which was translated into English in the backend of the online database. A total of 22 trained FWs were assigned to probe the households within or after 2 weeks of the deceased and collected the VA information under the supervision of 3 field supervisors. All the information were stored on an online cloud platform in the urban HDSS server. All the processes and transformations are documented in the urban HDSS guidelines (Figure 2).

Verbal autopsy coding/Assigning causes of deaths

All the VA information was sent to a trained verbal autopsy specialist of the 10th version of the International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) manual.24 The specialist reviewed the completed VA data and the narratives of the death history to determine the immediate and underlying causes of death according to the four-character code, where the first numeric character was assigned to the reviewer’s code, and later three characters were mandatorily represented by the ICD-10 code.

Data preparation and management

For this study, multiple urban HDSS databases were used. We integrated other surveillance data for bivariate analyses. For example, the household assets, mother’s ID, pregnancy history of the mother of the deceased child, and birth history of the deceased child were linked in the analytical dataset for the socioeconomic (wealth quintile), mother-child socio-demographic, and pregnancy-related characteristics. We extracted the mode of delivery place of delivery information of the deceased child from the birth history dataset, while the history of pregnancy-related services (ANC and PNC visits for both mother and child) was extracted from the pregnancy history dataset. Among the 155 children, 12 migrated into the DSS area before their deaths, resulting in missing pregnancy and birth history. The data management team and FWs recollected these information from those 12 migrated children’s families through revisiting and mobile contacts. This was done because these children’s VA had no information on these covariates and wanted to incorporate that information with the causes of their deaths. Later, the data management team checked the final data. The final data includes - demographic and socioeconomic information of the household of the deceased children (sex, age, wealth status-components, location of the slum), socioeconomic information of their mothers (age, education, and occupation), deceased’s birth history (mode of delivery, place of delivery), pregnancy history (ANC and PNC visits for both mother and child), and the verbal autopsy-ICD-10 codes.

Variables of interest and analyses

The cause of death of a child younger than 5 chronological years is the main outcome variable of this study. Besides, we recategorized these causes of death into neonatal (<29 days), infant (<1 year), and child deaths (1-4 years), for example, please see the Online Supplementary Document, Table S3-S5. All the causes of deaths were recategorized into 9 broad categories based on death causes nature with the help of the verbal autopsy specialists (MMAB) and maternal and child health specialists (AR), detailed codes were given in Online Supplementary Document, Table S6. These causes of under-5 mortality were evaluated by deceased age (neonatal, infant, and child) and sex (boy and girl), mother’s education (No education, Primary, Secondary and higher) and working status (Yes, No), slum locations (Dholpur, Korail, Mirpur, Shaympur, Tongi), household wealth quintile (Poorer, Poor, Middle, Rich, Richer), place of delivery (Home and Facility), mode of delivery (Normal, Cesarean), ANC visits (Yes, No) and PNC visits (Yes, No) for children.

The sample characteristics of the under-5 death children were given using the frequency distribution for the categorical variables, while the mean and standard error were reported for the continuous variables. The recategorized causes were reported using the percentage distribution and reported using the graphical presentation. We have also observed the proportional variation of the deaths caused by explanatory variables. All the analyses were conducted in Stata Windows version 15.1 (Stata.corp, TX). The whole paper was prepared following the reporting STROBE checklist for the cross-sectional study (See Online Supplementary Document, Table S1).25

Patients and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in this study, including data collection, analysis and interpretation.

RESULTS

Background characteristics

A total of 155 mothers/caregivers of deceased children under-5 years were interviewed during October 2020–2021 and used in this study. The proportion of neonate deaths was higher (105, 67.74%), followed by infant deaths (34, 21.94%) and child deaths at the age of 1–4 (16, 10.32%) (Table 1).

The overall sex ratio (boy vs girl) of the deaths was (67.7% vs 32.3%), whereas (68.6% vs 31.4%) for neonates, (61.8% vs 38.2%) for infants, and (75.0% vs 25.0%) for children at the age of 1–4 years. They mostly belong to poor (poorest and poorer) households (43.87%), whereas 41.91% of neonates, 52.9% of infants, and 37.5% of children (aged 1-4 years) belong to the poorest and poorer households. Most of the mothers of the deceased children ranging from 62% to 74.3%, had no occupation (housewife, student, disabled, or unemployed), while 47.7% of the mothers had 1–4 years of education, followed by 6+ years of education (29.0%), 23.2% had no education.

About 50.97% of the deceased were born at home, while 47.74% were born in a facility; the remainder were born elsewhere (on the road, in a transport facility). Around 80% of the mothers of the deceased took ANC services; 76.8% gave birth by normal vaginal delivery; and 39.3% and 47.1% took PNC services for the mother and the deceased child, respectively. Half of the children died in the urban slum area when their mother’s age reached 23.6 years (interquartile range: 20.1, 29.4). Korail slum shared the most neonatal, infant, child, and overall under-5 deaths by 39.0%, 67.6%, 37.5%, and 45.2%, respectively.

Causes of deaths

Birth asphyxia accounted for 1 out of 4 child deaths, followed by other infections (16.77%) and pneumonia (16.13%) (Figure 3). External causes, such as accidents, drownings, and other unknown causes, account for 9% of overall child deaths. Neonatal cerebral ischemia, prematurity and low birth weight, congenital anomalies and diarrhoea accounted for 7.7%, 6.4%, 5.2% and 4.2% of child deaths, respectively. However, we also found that 9% of deaths occurred due to other causes including malnutrition. Detailed causes of death were also provided in the Online Supplementary Document, Table S2.

We also observed a variation in the causes of deaths by sex of the deceased children (Figure 4). For boy children, 25.7% died due to birth asphyxia, followed by pneumonia (20%) and other infections (16.2%), neonatal cerebral ischemia and external causes (7.6%) and other causes accounted for 6.7% of deaths. For girl children, birth asphyxia is also prominent (24%), followed by other infections (18%), other causes (14%) and external causes (12%) than all other causes of death. However, in comparison, more boys died due to birth asphyxia, pneumonia, congenital anomalies and diarrhoea than girl children, where the girl children were more died due to other infections, external causes, other causes, cerebral ischemia, and prematurity and low birth weight.

Table 2 shows the age-specific causes of mortality fraction. For neonates, the leading causes of death are birth asphyxia (37.1%), followed by other infections (20.0%), cerebral ischemia (11.4%), prematurity and low birth weight (9.5%), and pneumonia (7.6%). Congenital anomalies caused 3.8% of neonatal deaths. For infants, the leading causes of death were pneumonia (38.2%), followed by external causes (17.6%), congenital anomalies and other infections (11.8%), other infections (14.7%) and diarrhoea (8.8%). For children aged between 1–4 years, other causes accounted for 31.2% of deaths followed by diarrhoea, and pneumonia (25%), and external causes (18.7%).

Mother’s occupation and education are important for under-five deaths (Table 2). We found that child deaths due to birth asphyxia (25.9%), pneumonia (17.9%), other infections (17%), and neonatal cerebral ischemia (8.9%) were more prevalent among children of non- working mothers, while children of working mothers died mostly due to other causes (14%), external causes (11.6%), congenital anomalies (7.0%). The mother’s occupation did not vary much for prematurity, low birth weight, and diarrhoeal causes of child deaths. However, children of non-educated mothers were more likely to die due to birth asphyxia (27.8%), pneumonia (22.2%), external causes (13.9%), prematurity, low birth weight, and congenital anomalies than educated mothers. Contrarily, deaths by other infections (21.6%), neonatal cerebral ischemia (15.6%), and other causes (13.3%) were higher for the children of educated mothers with primary, secondary and higher education, respectively.

Of the normally delivered babies, 26% died due to birth asphyxia, while 22.2% of children died during Caesarean delivery from the same cause (Table 2). Pneumonia-related deaths were higher for the babies born by Caesarean delivery (19.4%) than for normal delivery (15.1%), as were infectious causes (19.4% vs 16.0%). Deaths due to prematurity and low birth weight were higher in normal delivery (6.7%) than in caesarean sections (5.6%), where congenital anomalies were higher among caesarean babies (13.9%) compared to normal births (2.5%). Neonatal cerebral ischemia and other causes of death were higher in normal than in caesarean delivery (8.4% vs 5.6%). Regarding the place of delivery, there was no noticeable difference in birth asphyxia, neonatal cerebral ischemia, other infections, and other causes of under-5 deaths (Table 2). In urban slums, death due to pneumonia (21.0%), prematurity and low birth weight (7.6%), diarrhoea (6.2%), and other causes (2.5%) were higher for under-5 deaths with home births compared to facility births of those causes. Deaths due to other infections (24.3%) and congenital anomalies (6.8%) were found to be higher for those who were born in facilities.

About 35% of the children of women who did not receive any ANC visits died of birth asphyxia, and nearly 20% of them accounted for pneumonia (Table 2). Diarrhoea and other infections lead to 13% of child deaths among women who did not receive any ANC visits. About 33% of the children who did not receive any PNC visits died of birth asphyxia, and nearly 17% of them accounted for pneumonia. Diarrhoea and other infections led to 17.1% of child deaths who did not receive any PNC visits (See Table 02). Premature and low birth weights and neonatal cerebral ischemia accounted for 6.1% and 3.7% of child deaths. Results also indicate that, among the PNC-received children, nearly 21.9% of them died due to other infections, followed by birth asphyxia (16.4%), pneumonia (15.1%) and neonatal cerebral ischemia (12.3%). In contrast, congenital anomalies, premature and LBW, and diarrhoea caused 9.6%, 6.8% and 4.1% of child deaths, respectively, who received PNC visits.

DISCUSSION

We showed the causes of death of under-5 children by different socio-demographic and delivery-related attributes in the urban informal settlements in Bangladesh. Expectedly, the neonatal period is a crucial and vulnerable period for under-5 child survival. Similar to the national estimates, we also found that birth asphyxia, pneumonia, and infectious causes are the most common causes of death; however, preventable external and other causes of deaths are quite prominent. We also found variation in the causes of death by informal settlement location, household socioeconomic status, and mother’s socioeconomic status, but it was not statistically significant. Besides, several causes dominate over the mode and place of delivery.

The prevalence of causes of neonatal deaths in our study yields a similar result to the national estimates, where the major causes of neonatal deaths were birth asphyxia and infection. Other causes of neonatal deaths were different compared to national estimates. We found more neonates in urban informal settlements died of infectious diseases (20 vs 12%) than national estimates, while deaths caused by prematurity and low birth weight (9.5 vs 19%), pneumonia (7.6 vs 13%), and congenital anomalies (3.8 vs 7%) were comparatively lower for neonatal deaths in HDSS sites.14 In urban informal settlements, deaths due to cerebral ischemia are found to be common in neonates. Similar findings were also found for post-neonates (<1 year) and children aged 1–4 years compared with the national estimates and other studies.7,12,14

These deaths were attributed to and can be prevented with appropriate healthcare services in the study areas. One-stop centres for mother and child along with a particular emphasis on the vulnerable community- including slums can be a good fit for such deaths prevention. However, there is a lack of healthcare facilities and its operations are scatteredly regulated in the study areas. A previous MANOSHI model is currently becoming a social enterprise model where the model integrated the door-to-door prenatal services of its catchment areas, focusing on the slum and vulnerable population.10,26 Besides, the contribution of urban primary healthcare service delivery project (UPHCSDP) is incorporated into the slum areas as well.27 Recently, UNICEF has been providing integrated primary healthcare services in slum areas by developing a comprehensive primary healthcare model called “Aalo clinic”.28 However, Aalo clinic only offers primary healthcare services where the delivery care is not yet integrated into their model. Moreover, numerous private clinics and hospitals also provide services for the slum population with minimum costs. In addition, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and Local Government Department also provided training to the traditional birth attendants to ensure the safe mother-child healthcare services,29 accounting for 22% of live births during the prenatal and postnatal period.30 However, there is a gap between appropriate referral systems for any emergency and one-stop crisis moments for maternal and neonatal healthcare services. Despite all of these, there are still more than 30% of women who deliver their babies with the help of traditional birth attendants.30

All these under-5 deaths were distributed by geographical locations, which means the interventions needed to be modified based on the characteristics of the location. We found that the external causes were located in the busy, road-side area and lakes aside in the informal settlements of Korail and Shaympur. All these external causes include major drowning, accidental suffocation, and unknown sudden deaths. Therefore, local awareness and strengthening of local governance on transportation, sanitation, and restructuring of water-bounds can be used to prevent these child deaths. Besides, these deaths mostly occurred in households of lower wealth status. Therefore, intervention in local healthcare facilities while prioritizing the local characteristics of area-wise major causes of death could also help to prevent other infectious and neonatal causes of child deaths.

Pneumonia and other infectious diseases are more prevalent causes of under-5 deaths, commonly for those mothers who either received ‘no’ or ‘primary’ education. Nationally, the pattern was the same for infectious and vector-borne diseases like pneumonia, diarrhoea, and other infections.14 In the informal settlements, birth asphyxia and congenital anomalies were higher for those women with no education, whereas cerebral ischemia was found to be higher for mothers with secondary and higher education. There is a clear picture of how a mother’s low education may lead to a child’s death toll when the causes of death are infectious and vector-borne. Recent experiments found that maternal education reduces under-5 mortality by 20%, where greater wealth status, higher health-related knowledge, health-seeking behaviours, and women’s empowerment are associated with child mortality.31 Another study based on the national database found that under-5 deaths caused by infectious diseases were more common in mothers with less education.32 Lack of maternal awareness and education also have greater impacts on external causes of death, as mothers with low education are less likely to be aware of childcare.

Mothers in informal settlements are mostly working outside. Reports suggest that most working mothers in the study area are engaged in health-risk jobs like garment workers, domestic workers, and skilled/unskilled labour.33 Most of the household members in the urban informal settlements were engaged in outside work for daily earnings, leaving their children behind in the house, either alone or with younger or older ones in the family. This inadequate attention to childcare can create an insecure environment for the child and cause accidents. Our study findings support this fact—the external and other causes of death were high for those children whose mothers were working outside (or had an occupation). Contrarily, children of non-occupied mothers were more likely to die due to infectious diseases—in this study, pneumonia and serious infections—though deaths due to other causes of infection were found to be lower among the non-occupied mothers. According to Akinyemi et al. (2018), infant mortality was higher among children of non-working mothers, and the difference was greater during the first 12-59 months of life.34 Other socioeconomic factors underpin the major causes of maternal occupation and child deaths,35 child nutrition in relation to breastfeeding and child feeding practices,36,37 child vaccination,38 and changing patterns of childcare practices.39,40 Working mothers get less time for such protective practices for their children, which is indirectly associated with under-5 deaths. The majority of these deaths can be prevented by adopting the prevent, protect, and treat strategy and human rights-based approach to reduce and eliminate preventable mortality and morbidity of children under-5 years of age and scaling them up at a low intervention cost to poor settlements.41

Strengths and Limitations

This study is a snapshot of the causes of death of children in the urban poor and informal settlements. Assigning deaths caused by one verbal autopsy specialist is our main limitation in this study. These limitations can be overlooked as the physician was institutionally assigned to Matlab, Chakaria, and the Urban HDSS and has worked for over 20 years. The second limitation was the number of under-five deaths, which is quite low to represent generalizability for the same population across the country. Due to the lack of all birth information, we cannot present the population level burden and the risk of cause-specific mortality in our study.

CONCLUSIONS

The study’s findings indicate that most of the under-5 deaths occurred during the neonatal period. Furthermore, the most frequent causes of death are birth asphyxia, pneumonia, and infectious diseases, but we also discovered that preventable external and other causes of death are quite common. These causes vary depending on household status, the mother’s socioeconomic situation, and the delivery methods of urban slum areas. Most of these deaths can be preventable under appropriate interventions-related to the health system strengthening regarding the healthcare coverage, quality of services and non-discriminatory healthcare services for the urban poor children. Therefore, urban poor-focused newborn health interventions are necessary. Moreover, adequate attention and additional safety measures might avoid accidental deaths of under-5 children; health education and awareness among mothers could prevent unnecessary infectious deaths of children; and proper pregnancy and delivery care for expectant slum women could prevent neonatal fatalities.

Acknowledgements

icddr,b acknowledges to the Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, the Embassy of Sweden and the Asian Development Bank for initial support to establish the urban HDSS and UNICEF/Sida for continuation of these research efforts. icddr,b is also grateful to the Government of Bangladesh for its long-term financial support and also to international core donors: Canada.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Research and Ethical Review Committee of icddr,b (Protocol # 15045).

Data availability

Data used in the analyses for this study are available on request, subject to completion of a data sharing agreement. For additional information please refer to http://www.icddrb.org/policies.

Funding

This work was funded by UNICEF (Grant # 01713).

Authorship contributions

MAB, AR and AnR conceptualized the study with inputs from MZI. AR obtained funding and served as the principal investigator of the project. RC developed data collection tools and supervise the data collection. MAB, RC and AR extracted and prepared the datafile, MAB conducted the data analyses with inputs from AnR, AR, SMAH. MAB, SS and BKS wrote the first draft of the manuscript with inputs from AnR, AR, and MZI. MK, MZM, MZJ, JF, MV MARA and SMAH reviewed and commented on the subsequent drafts of the manuscript. All authors were consented for publication.

Disclosure of interest

The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form and disclose no relevant interests.

Additional material

This paper has an Online supplementary document that contains 6 Supplementary Table S1-S6.

Supplementary Table S1: STROBE Statement—Checklist of items that should be included in reports of cross-sectional studies

Supplementary Table S2. Major causes of deaths (under-5 children)

Supplementary Table S3. Major causes of deaths for neonatal

Supplementary Table S4. Major causes of deaths for infant

Supplementary Table S5. Major causes of deaths for child 1-4 years

Supplementary Table S6. Classification and reclassification of causes of deaths

Correspondence to:

Abdur Razzaque

Health Systems and Population Studies Division, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b)

68 Shaheed Tajuddin Ahmed Sarani, Mohakhali, Dhaka 1212

Bangladesh

[email protected]

.png)

.png)

_by_sex_of_the_children.png)

.png)

.png)

_by_sex_of_the_children.png)